Summary

This post on Homelessness is 1 of 3 issues that US onAir curators are focusing on in the Veterans category.

Homeless veterans are persons who have served in the armed forces who are homeless or living without access to secure and appropriate accommodation.

Many of these veterans suffer from post traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety disorder that often occurs after extreme emotional trauma involving threat or injury. Causes of homelessness include:[2]

- Disabilities – physical injury or mental illness

- Substance abuse – drug abuse or alcoholism

- Family breakdown

- Joblessness and poverty

- Lack of low cost housing

- Government policy

OnAir Post: Homelessness

News

PBS NewsHour – December 24, 2023 (06:00)

The number of Americans experiencing homelessness is now at its highest since records started being kept in 2007, according to estimates in a new report from the federal government. 2023 saw a 12 percent increase in homelessness over the previous year, the biggest one-year jump on record. John Yang speaks with Ann Oliva, CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness, to learn why.

About

Check the Veterans post for the party positions, committees, government agencies related to Homelessness issues.

Challenges

Lack of Affordable Housing:

- Veterans often struggle to afford market-rate housing, especially in high-cost areas.

- Government-supported housing programs, such as the VA’s Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF), face funding shortfalls and have long waitlists.

2. Limited Access to Healthcare and Services:

- Veterans experiencing homelessness may have complex health conditions and mental health issues.

- Barriers to accessing healthcare, such as transportation and bureaucratic hurdles, prevent them from getting necessary care.

- Shortage of qualified mental health professionals who specialize in treating veterans.

3. Stigma and Discrimination:

- Veterans experiencing homelessness often face negative attitudes and judgment from society.

- Stigma can hinder their ability to seek help and find employment.

- Discrimination in housing and employment markets exacerbates their vulnerability.

4. Substance Use and Mental Health Issues:

- A significant proportion of veterans experiencing homelessness have substance use disorders or mental health conditions.

- These issues can lead to homelessness and make it difficult to maintain stable housing.

- Lack of access to treatment and support programs can perpetuate the cycle of homelessness.

5. Financial Instability and Unemployment:

- Veterans experiencing homelessness often lack job skills and experience.

- Chronic joblessness can lead to financial instability and make it difficult to secure housing.

- Barriers to employment, such as lack of identification or criminal records, compound their challenges.

6. Lack of Social Support:

- Many veterans experiencing homelessness have lost contact with family and friends.

- Social isolation can contribute to loneliness, depression, and a sense of hopelessness.

- Lack of social support can undermine their ability to seek help and maintain stability.

7. Bureaucratic Barriers:

- Veterans experiencing homelessness often must navigate a complex system of government agencies to access benefits and services.

- Lack of coordination between agencies can create delays and hinder their progress toward self-sufficiency.

- Lengthy application processes and eligibility requirements can discourage veterans from seeking assistance.

8. Policy Gaps:

- Current homelessness prevention and response policies are fragmented and insufficient to meet the needs of veterans.

- Long-term housing solutions, such as affordable housing vouchers, are not available in all areas.

- Lack of funding for evidence-based programs and research hampers efforts to address the root causes of veteran homelessness.

Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation

Solutions

Multi-Pronged Approach:

- Housing-First Model: Prioritizing providing stable housing to veterans experiencing homelessness without preconditions (e.g., sobriety, mental health treatment).

- Permanent Supportive Housing: Offering affordable housing combined with wraparound services (e.g., mental health care, case management) to address underlying issues contributing to homelessness.

Supportive Services:

- Mental Health and Substance Use Treatment: Providing comprehensive services to address co-occurring mental health conditions and substance use disorders.

- Case Management: Assisting veterans with accessing housing, benefits, and other essential services.

- Vocational Rehabilitation: Helping veterans secure employment and education opportunities to gain financial stability.

Economic Support:

- VA Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF): Providing financial assistance for housing, utility bills, and other urgent needs.

- Veteran Emergency Housing Grants (VEHG): Offering short-term rental assistance to prevent homelessness.

- VA Medical Center Domiciliary Care: Providing transitional housing and support services for veterans with chronic conditions who require medical oversight but not acute care.

Community Partnerships:

- Collaborations with Nonprofits: Partnering with organizations that provide housing, food assistance, and other services to veterans in need.

- Law Enforcement and First Responders: Establishing relationships with local authorities to identify and assist veterans experiencing homelessness.

- Community Outreach: Engaging with veterans in shelters, transitional housing, and other community settings to connect them with resources.

Policy and Legislation:

- Homeless Veterans’ Reintegration Program: Expanding the VA’s program to provide supportive services, job training, and case management to homeless veterans.

- Veterans Access to Care Through VA Choice and Accountability Act: Improving access to VA healthcare services for veterans, including those experiencing homelessness.

- Housing First for Veterans Act: Establishing a national goal of ending veteran homelessness and prioritizing housing-first approaches.

Data-Driven Approach:

- Homeless Management Information System (HMIS): Collecting and analyzing data on veteran homelessness to identify trends and inform policy decisions.

- Performance-Based Contracting: Funding organizations based on their effectiveness in reducing veteran homelessness and improving outcomes.

- Evaluation and Research: Conducting ongoing evaluations to assess the effectiveness of programs and identify areas for improvement.

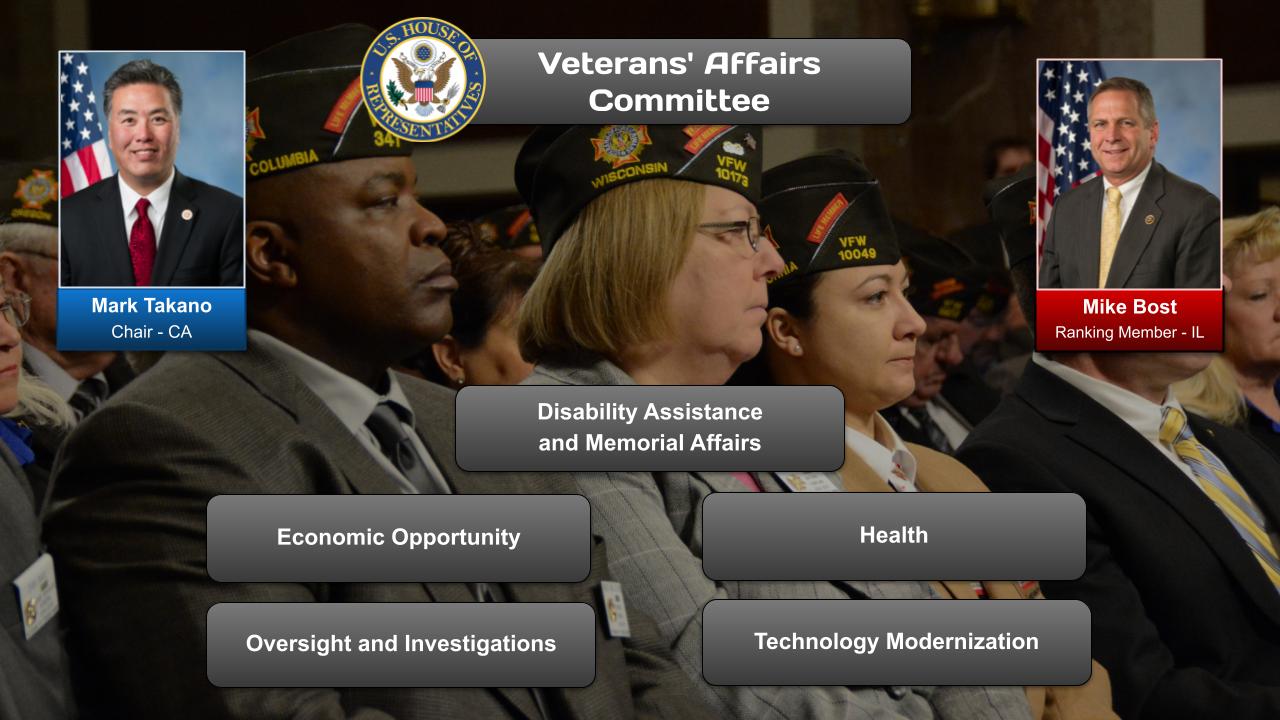

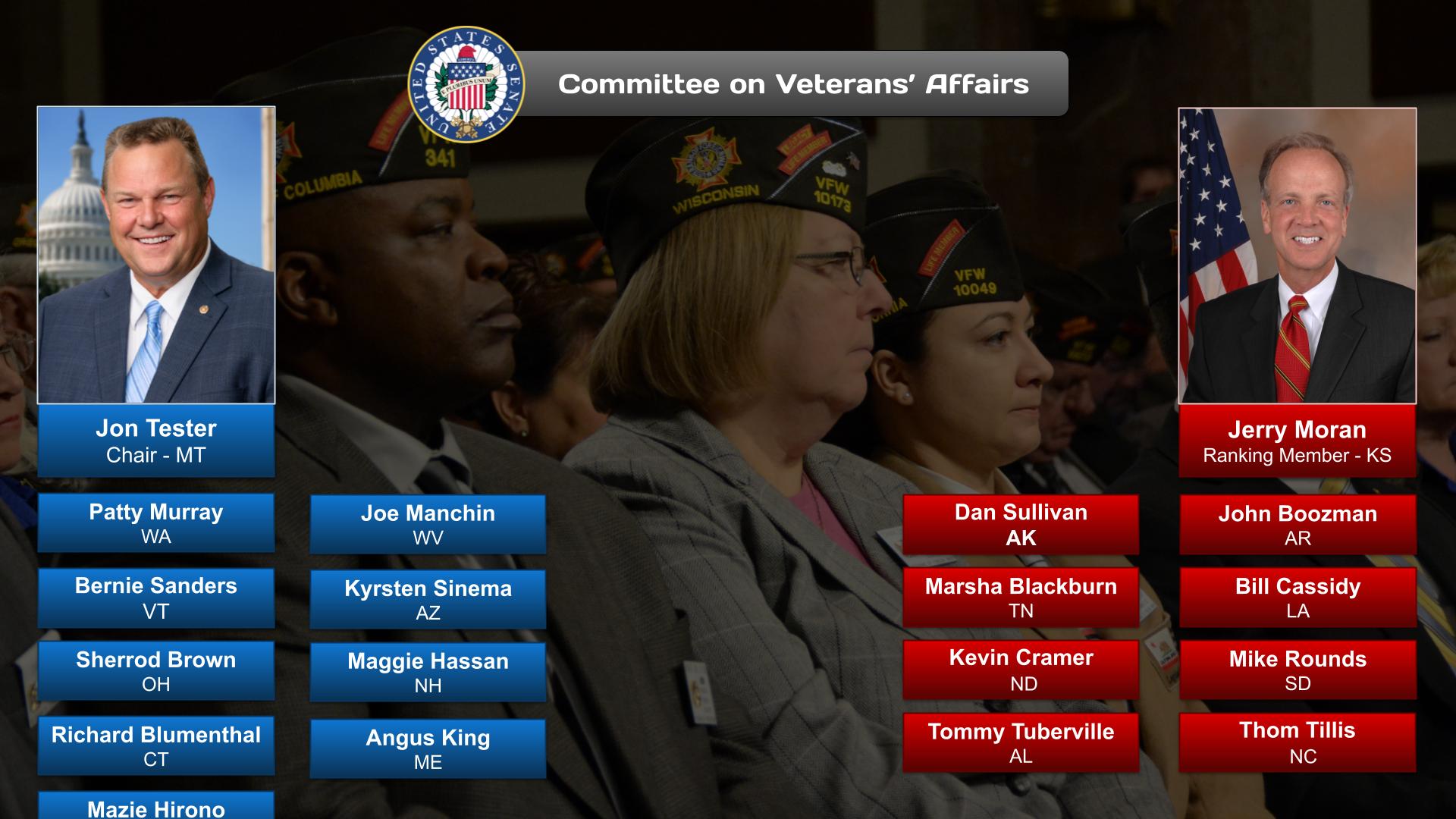

Source: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) National Coalition for Homeless Veterans (NCHV) National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH) American Legion Salvation Army Other Resources Source: Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 1996 (Public Law 104-262) 2. HUD-VA Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) Program (Public Law 108-39) 3. Homeless Veterans Comprehensive Assistance, Resources, Education, and Training (HVCARVET) Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-387) 4. Veterans Homelessness Prevention and Treatment Act (VHPTA) of 2017 (Public Law 115-35) 5. VA MISSION Act of 2018 (Public Law 115-182) 6. American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (Public Law 117-2) 7. Veterans Integrated Services Network (VISN) 10 Homeless Program (Public Law 117-167) Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation H.R. 477 – The Homelessness among Veterans Elimination and Recovery (HAVER) Act S. 547 – The Homeless Veterans Employment Assistance Act H.R. 1161 – The Veterans Health Equity and Recovery (VHEAR) Act S. 1152 – The Veterans Homelessness Prevention Act H.R. 1434 – The Housing for Homeless Veterans Act Additional Legislative Initiatives: These bills and initiatives represent a comprehensive approach to addressing the challenges of veteran homelessness in the United States. They provide increased funding for housing, healthcare, employment, and other supportive services, while also promoting innovation and collaboration among government agencies and community organizations. Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Senate Committees: House Committees: Joint Committees: Subcommittees Relevant to Veteran Homelessness: These committees play a vital role in overseeing the federal government’s efforts to address veteran homelessness, including funding, policy development, and program implementation. They hold hearings, conduct investigations, and make recommendations to improve the coordination and effectiveness of services for homeless veterans. Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Department of Labor (DOL) Department of Justice (DOJ) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Additional Agencies: Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation VA Homeless Providers Grant and Per Diem Program 2. Supportive Services for Veteran Families (SSVF) 3. HUD-VASH (Housing for Homeless Veterans with Supportive Services) 4. Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (VASH) 5. VA Healthcare for Homeless Veterans 6. Veterans Benefit Administration (VBA) Homelessness Assistance 7. Transitional Housing and Placements for Homeless Veterans (THP) 8. VA Supportive Services Center for Veteran Families (SSCVF) 9. VA Homeless Management Information System (HMIS) 10. National Coalition for Homeless Veterans (NCHV) Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Nonprofit Organizations Think Tanks and Research Institutions Service Providers Homeless veterans are persons who have served in the armed forces who are homeless or living without access to secure and appropriate accommodation.[1] Many of these veterans suffer from post traumatic stress disorder, an anxiety disorder that often occurs after extreme emotional trauma involving threat or injury. Causes of homelessness include:[2] Veteran homelessness in America is not a phenomenon only of the 21st century; as early as the Reconstruction Era, homeless veterans were among the general homeless population.[3] In 1932, homeless veterans were part of the Bonus Army.[4] In 1934, there were as many as a quarter million veterans living on the streets.[5] During the Truman Administration, there were one hundred thousand homeless veterans in Chicago, and a quarter of that number in Washington, D.C.[6] In 1987, the number of homeless veterans was as high as three hundred thousand.[7] Estimates of the homeless population vary as these statistics are very difficult to obtain.[8] In 2007, the first veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom – Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom began to be documented in homeless shelters.[9] By 2009 there were 154,000 homeless, with slightly less than half having served in South Vietnam.[10] According to the VA in 2011, veterans made up 14% of homeless adult males, and 2% of homeless adult females, and both groups were overrepresented within the homeless population compared to the general population.[11] The overall count in 2012 showed 62,619 homeless veterans in the United States.[12] In January 2013, there were an estimated 57,849 homeless veterans in the U.S., or 12% of the homeless population.[13] Just under 8% were female.[14] In July 2014, the largest population of homeless veterans lived in Los Angeles County, with there being over 6,000 homeless veterans, out of the total estimated 54,000 homeless within that area.[15] In 2015, a report issued by HUD counted over 47,000 homeless veterans nationwide, the majority of whom were White and male.[16] In 2016, there were over 39,000 homeless veterans nationwide.[17] A Corps in terms of military size. As of January 2017, the state of California had the highest number of veterans experiencing homelessness. There were an estimated 11,472 homeless veterans.[18] The biggest population of homeless veterans, after California, in 2017 lived in Florida – an estimated 2,817, and in Texas – 2,200. Many programs and resources have been implemented across the United States in an effort to help homeless veterans.[19] HUD-VASH, a housing voucher program by the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development and Veterans Administration, gives out a certain number of Section 8 subsidized housing vouchers to eligible homeless and otherwise vulnerable U.S. Armed Forces veterans.[20] In 1887, the Sawtelle Veterans Home was constructed to care for disabled veterans, and housed more than a thousand homeless veterans.[21] Other such old soldiers’ homes were built throughout the United States,[22] such as the one in New York.[23] These homes became the predecessors of the Veteran Affairs’ medical facilities.[24] According to a study in 2014, veterans are slightly more likely than non-veterans to be homeless; 9.7% of the general population are veterans, but 12.3% of the homeless population are veterans.[25] These risk factors were found by using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). This is the first systemic review to summarize research on risk factors for US veterans experiencing homelessness. They evaluated thirty-one studies from 1987 through 2014. The risk factors that are most common among this population are substance abuse disorders and poor mental health, followed by low income and other income related issues, a lack of support from family and friends, or weak social networks.[25] The needs between veterans and non-veterans experiencing homelessness can differ. A study was implemented by the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness (CICH) in 2004 by the Interagency Council on Homelessness. They used eleven sites around the United States tracked data for one year by comparing 162 chronically homeless veterans to 388 chronically homeless non-veterans.[25] Both groups were enrolled in a national supported housing initiative over a one-year period and several differences were noted. The first was that the veterans tended to be from an older age group, identified as male, and were more likely to have completed high school.[25] While in enrolled in supported housing, the mental health of both groups improved through mental health services offered. However, veterans were reported to make greater use of the outpatient mental health services compared to non-veterans. Both groups also gradually reduced the use of health services once housing was obtained, therefore, this suggests that the program is effective in reducing clinical needs among chronically homeless of adults in general. On November 3, 2009, United States Secretary Eric K. Shinseki spoke at the National Summit on Homeless Veterans and announced his plan.[undue weight? ] Along with President Barack Obama, Shinseki outlined a comprehensive five-year plan to strengthen the Department of Veterans Affairs and its efforts to end veteran homeless.[26] The goal was to end veteran homelessness by 2015, but because of budget constraints that has now been pushed to 2017.[27] The plan focused on prevention of homelessness along with help for those living on the streets.[28] The plan would expand mental health care and housing options for veterans, and would collaborate with:[28] The prominent role of the Department of Veterans Affairs and its joined up approach to veteran welfare help to distinguish the US response to veteran homelessness internationally.[29] In 2009, a hotline was established to assist homeless veterans. As of December 2014, of the 79,500 veterans who contacted the call center, 27% were unable to speak to a counselor, and 47% of referrals led to no support services provided to the homeless veteran.[30] A study published in the American Journal of Addiction showed a link between veterans’ trauma of mental disorders and their substance abuse.[31] A study conducted by O’Connell, Kasprow and Rosenheck is a secondary analysis of data from the evaluation of the HUD-VASH initiative that began in 1992 to provide housing for veterans with psychiatric disorders. They compared the results of three kinds of interventions with 460 veterans across nineteen sites in the country. They were assigned to three groups; one group was given a voucher and intensive case management, one group was given intensive case management only, and one group was given standard care only.[32] Intensive case management included help locating an apartment, while standard care which consisted of short-term broker case management provided by the Health Care for Homeless Veterans outreach workers. An evaluation assistant conducted follow up interviews every three months for up to five years. Through that they found that individuals in the intensive case management group had lower scores on quality of life which was measured by the Lehman Quality of Life Interview. This is a structured questionnaire to assess the life circumstances of persons with severe and persistent mental illness.[33] Housing failure is defined as experiencing homelessness for at least one day. Before intake, 43% (n=170) has been homeless between one and six months and 27% (n=105) has experienced homelessness for two years or more.[32] The risk factors are the greatest in the first few months of being housed due to the more structured and supervised setting. Weekly face to face contact, community-based care and services offered by the VA were encouraged, which is vastly different from the life they were used to before this program. The veterans were tracked for five years and the statistics changed vastly over that time. 72% of participants remained housed after one year (N=282), 60% after two (N=235), 52% after three (N=204), 47% after four years (N=184) and 36% after five years (N=141) (5). Those in the HUD-VASH group has a lower risk of returning to homelessness over the course of five years had an 87% lower risk compared to those in intensive care management only group and 76% compared to those in standard care.[32] The greatest risk factor for returning to homelessness was either due to drugs or due to PTSD. Overall, after five years of follow up, 44% of all participants (N=172) returned to homelessness for at least one day after being successfully placed into housing.[32] To end homelessness among veterans, new resources and program expansions were introduced. One of the goals set by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Developments Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) is to place veterans experiencing homelessness in permanent housing. A housing first approach has been introduced to help support this initiative. One of the goals of Housing First is the rapid placement of veterans to directly from the streets to a permanent home. Housing first approach works with the HUD supplying housing assistance through a voucher program while the VA provides case management and supportive services through its healthcare system.[34] By having permanent housing, there is a decrease in the usage of shelters, hospitals and correctional facilities. This program is available in all 50 states, the District of Columbia and Guam. A study by Montgomery, Hill, Kane and Culhane was a demonstration that was initiated in 2010 and studied the housing methods in the United States for homeless veterans. They evaluated the efficiency of the Housing First (HF) approach compared to a Treatment as Usual (TAU) approach. HF targeted those were experiencing street homelessness while TAU served more women and families. Veterans placed in HF were offered services such as social workers, vocational trainers, a housing specialist and access to a psychiatrist. Most importantly, HF would issue a housing voucher at the time of lease signing for pre-inspected apartments which were maintained by a contractor. Veterans in the TAU approach received the standard VA case management services for HUD-VASH.[35] In TAU, they remained at their current placement, which could sometimes include an emergency shelter, or they were placed in transitional housing or residential treatment programs. The study found that the HF has the most effective model in accessing permanent housing and has shown efficiency in reducing rates of homelessness with veterans.[35] Compared to TAU, HF was more successful at quickly moving veterans into permanent housing, their moving process took approximately one month while the TAU approach took about six months.[35] The housing retention rate for HF was 98% and 86% for TAU, meaning that those using the HF model were more likely to maintain housing stability.[35] In addition to government provided aid, private charities provide assistance to homeless veterans as well.[36] These include providing some homeless veterans vehicles to live in,[37] and building permanent housing for others.[38] Advocating for the rights of homeless veterans through policy implementation and recommendations.[39] Throughout the nation, multiple organizations and agencies host “Stand Down” events where homeless veterans are provided items and services;[40] the first of these was held in San Diego, organized by Vietnam veterans, in 1988.[41] Homes For Heroes is a US for-profit and non-profit company that provides partner-savings to Veterans buying a home, and offers monetary grants to Veterans, and other medical professionals and first-responders buying a home.[42] Homes For Angels is a Texas program that provides discounted, affordable real estate services to Veterans and other first-responder service professions buying a home.[43] In November 2009, Secretary of Veterans Affairs (VA) Eric K. Shinseki set out the goal of ending veterans experiencing homelessness by 2017. While not all veterans are housed, the current housing initiatives such as the housing first model are ensuring that housing is obtained for a larger portion of veterans experiencing homelessness. In 2019, the HUD-VASH program was able to house more than 11,000 veterans.[44] Overall, since 2008, more than 114,000 veterans experiencing homelessness have been served through the HUD-VASH program.[44] Also, more resources are being implemented to assist with mental health and addiction. As of 2019, more than 78 communities and the entire states of Connecticut, Delaware and Virginia have effectively ended homelessness among veterans.[44] Websites

Legislation

Laws

New Bills in 2023-2024

Committees, Agencies, & Programs

Committees

Government Agencies

Programs & Initiatives

More Information

Nonpartisan Organizations

“Homeless veterans in the US” (Wiki)

Contents

Background

Demographics

Aid

Historical

Risk factors

Supportive housing for veterans compared to non-veterans

Department of Veterans Affairs

Housing interventions with veterans

Studies of housing first for veterans

Charity

Ending veteran homelessness

References

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link){{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)EXHIBIT 5.3: Demographic Characteristics of Homeless Veterans

External links