Summary

The power of the Executive Branch is vested in the President of the United States, who also acts as head of state and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces. The President is responsible for implementing and enforcing the laws written by Congress and, to that end, appoints the heads of the federal agencies, including the Cabinet. The Vice President is also part of the Executive Branch, ready to assume the Presidency should the need arise.

The Cabinet and independent federal agencies are responsible for the day-to-day enforcement and administration of federal laws. These departments and agencies have missions and responsibilities as widely divergent as those of the Department of Defense and the Environmental Protection Agency, the Social Security Administration and the Securities and Exchange Commission. See Government Executives for individual cabinet member bios.

Including members of the armed forces, the Executive Branch employs more than 4 million Americans.

OnAir Post: US Executive Branch

About

Overview

The three branches of the US Government are outlined below:

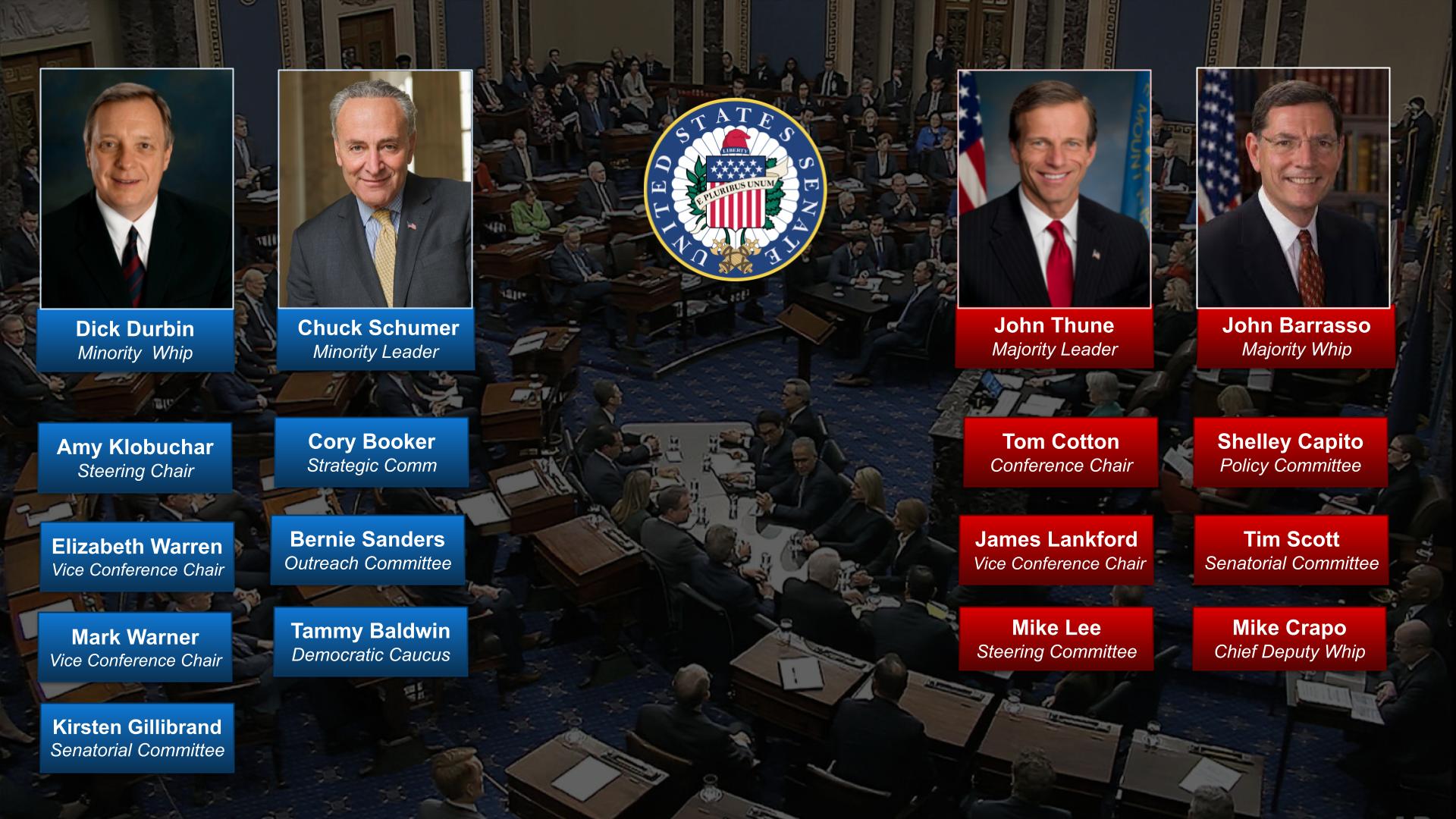

The Legislative Branch is made up of Congress (the Senate and House of Representatives) and special agencies and offices that provide support services to Congress.

The legislative branch’s roles include:

- Drafting proposed laws

- Confirming or rejecting presidential nominations for heads of federal agencies, federal judges, and the Supreme Court

- Having the authority to declare war

The Executive’s Branch key roles include:

- President – The president is the head of state, leader of the federal government, and Commander in Chief of the United States armed forces.

- Vice president – The vice president supports the president. If the president is unable to serve, the vice president becomes president. The vice president also presides over the U.S. Senate and breaks ties in Senate votes.

- The Cabinet – Cabinet members serve as advisors to the president. They include the vice president, heads of executive departments, and other high-ranking government officials. Cabinet members are nominated by the president and must be approved by the Senate.

The executive branch also includes executive departments, independent agencies, and other boards, commissions, and committees.

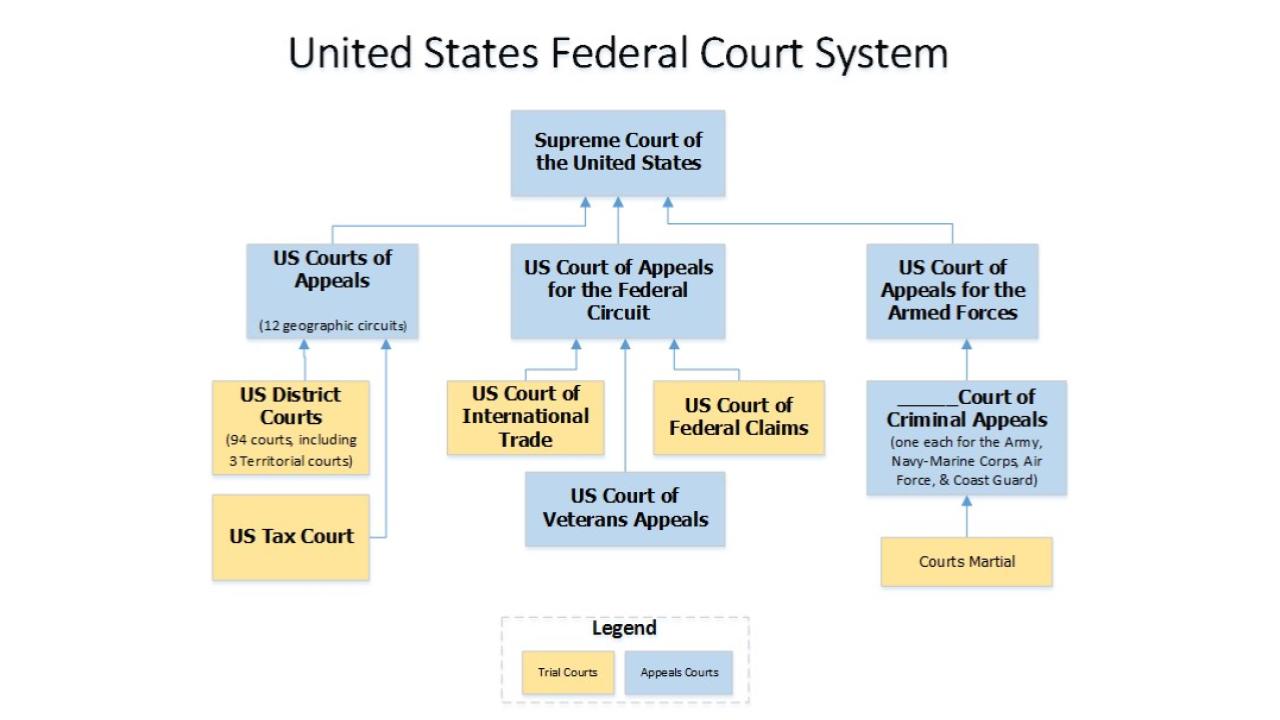

The Judicial Branch includes the Supreme Court and other federal courts.

It evaluates laws by:

- Interpreting the meaning of laws

- Applying laws to individual cases

- Deciding if laws violate the Constitution

How each branch of government provides checks and balances

The ability of each branch to respond to the actions of the other branches is the system of checks and balances.

Each branch of government can change acts of the other branches:

- The president can veto legislation created by Congress. He or she also nominates heads of federal agencies and high court appointees.

- Congress confirms or rejects the president’s nominees. It can also remove the president from office in exceptional circumstances.

- The Justices of the Supreme Court, nominated by the president and confirmed by the Senate, can overturn unconstitutional laws.

Source: Government website

Organization Chart of US Government

Web Links

The President

Source: White House website

The President is both the head of state and head of government of the United States of America, and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

Under Article II of the Constitution, the President is responsible for the execution and enforcement of the laws created by Congress. Fifteen executive departments — each led by an appointed member of the President’s Cabinet — carry out the day-to-day administration of the federal government. They are joined in this by other executive agencies such as the CIA and Environmental Protection Agency, the heads of which are not part of the Cabinet, but who are under the full authority of the President. The President also appoints the heads of more than 50 independent federal commissions, such as the Federal Reserve Board or the Securities and Exchange Commission, as well as federal judges, ambassadors, and other federal offices. The Executive Office of the President (EOP) consists of the immediate staff to the President, along with entities such as the Office of Management and Budget and the Office of the United States Trade Representative.

The President has the power either to sign legislation into law or to veto bills enacted by Congress, although Congress may override a veto with a two-thirds vote of both houses. The Executive Branch conducts diplomacy with other nations and the President has the power to negotiate and sign treaties, which the Senate ratifies. The President can issue executive orders, which direct executive officers or clarify and further existing laws. The President also has the power to extend pardons and clemencies for federal crimes.

With these powers come several responsibilities, among them a constitutional requirement to “from time to time give to the Congress Information of the State of the Union, and recommend to their Consideration such Measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.” Although the President may fulfill this requirement in any way he or she chooses, Presidents have traditionally given a State of the Union address to a joint session of Congress each January (except in inaugural years) outlining their agenda for the coming year.

The Constitution lists only three qualifications for the Presidency — the President must be at least 35 years of age, be a natural born citizen, and must have lived in the United States for at least 14 years. And though millions of Americans vote in a presidential election every four years, the President is not, in fact, directly elected by the people. Instead, on the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November of every fourth year, the people elect the members of the Electoral College. Apportioned by population to the 50 states — one for each member of their congressional delegation (with the District of Columbia receiving 3 votes) — these Electors then cast the votes for President. There are currently 538 electors in the Electoral College.

President Joseph R. Biden is the 46th President of the United States. He is, however, only the 45th person ever to serve as President; President Grover Cleveland served two nonconsecutive terms, and thus is recognized as both the 22nd and the 24th President. Today, the President is limited to two four-year terms, but until the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in 1951, a President could serve an unlimited number of terms. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected President four times, serving from 1932 until his death in 1945; he is the only President ever to have served more than two terms.

By tradition, the President and the First Family live in the White House in Washington, D.C., also the location of the President’s Oval Office and the offices of his or her senior staff. When the President travels by plane, his or her aircraft is designated Air Force One; the President may also use a Marine Corps helicopter, known as Marine One while the President is on board. For ground travel, the President uses an armored presidential limousine.

The Vice President

The primary responsibility of the Vice President of the United States is to be ready at a moment’s notice to assume the Presidency if the President is unable to perform his or her duties. This can be because of the President’s death, resignation, or temporary incapacitation, or if the Vice President and a majority of the Cabinet judge that the President is no longer able to discharge the duties of the presidency.

The Vice President is elected along with the President by the Electoral College. Each elector casts one vote for President and another for Vice President. Before the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804, electors only voted for President, and the person who received the second greatest number of votes became Vice President.

The Vice President also serves as the President of the United States Senate, where he or she casts the deciding vote in the case of a tie. Except in the case of tie-breaking votes, the Vice President rarely actually presides over the Senate. Instead, the Senate selects one of their own members, usually junior members of the majority party, to preside over the Senate each day.

Kamala D. Harris is the 49th Vice President of the United States. She is the first woman and first woman of color to be elected to this position. The duties of the Vice President, outside of those enumerated in the Constitution, are at the discretion of the current President. Each Vice President approaches the role differently — some take on a specific policy portfolio, others serve simply as a top adviser to the President. Of the 48 previous Vice Presidents, nine have succeeded to the Presidency, and five have been elected to the Presidency in their own right.

The Vice President has an office in the West Wing of the White House, as well as in the nearby Eisenhower Executive Office Building. Like the President, he or she also maintains an official residence, at the United States Naval Observatory in Northwest Washington, D.C. This peaceful mansion has been the official home of the Vice President since 1974 — previously, Vice Presidents had lived in their own private residences. The Vice President also has his or her own limousine, operated by the United States Secret Service, and flies on the same aircraft the President uses — but when the Vice President is aboard, the craft are referred to as Air Force Two and Marine Two.

Executive Office of the President

Every day, the President of the United States is faced with scores of decisions, each with important consequences for America’s future. To provide the President with the support that he or she needs to govern effectively, the Executive Office of the President (EOP) was created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EOP has responsibility for tasks ranging from communicating the President’s message to the American people to promoting our trade interests abroad.

The EOP, overseen by the White House Chief of Staff, has traditionally been home to many of the President’s closest advisers. While Senate confirmation is required for some advisers, such as the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, most are appointed with full Presidential discretion. The individual offices that these advisors oversee have grown in size and number since the EOP was created. Some were formed by Congress, others as the President has needed them — they are constantly shifting as each President identifies his or her needs and priorities. Perhaps the most visible parts of the EOP are the White House Communications Office and Press Secretary’s Office. The Press Secretary provides daily briefings for the media on the President’s activities and agenda. Less visible to most Americans is the National Security Council, which advises the President on foreign policy, intelligence, and national security.

There are also a number of offices responsible for the practicalities of maintaining the White House and providing logistical support for the President. These include the White House Military Office, which is responsible for services ranging from Air Force One to the dining facilities, and the Office of Presidential Advance, which prepares sites remote from the White House for the President’s arrival.

Many senior advisors in the EOP work near the President in the West Wing of the White House. However, the majority of the staff is housed in the Eisenhower Executive Office Building, just a few steps away and part of the White House compound.

The Cabinet

The Cabinet is an advisory body made up of the heads of the 15 executive departments. Appointed by the President and confirmed by the Senate, the members of the Cabinet are often the President’s closest confidants. In addition to running major federal agencies, they play an important role in the Presidential line of succession — after the Vice President, Speaker of the House, and Senate President pro tempore, the line of succession continues with the Cabinet offices in the order in which the departments were created. All the members of the Cabinet take the title Secretary, excepting the head of the Justice Department, who is styled Attorney General.

DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) develops and executes policy on farming, agriculture, and food. Its aims include meeting the needs of farmers and ranchers, promoting agricultural trade and production, assuring food safety, protecting forests and other natural resources, fostering rural prosperity, and ending hunger in America and abroad.

The USDA employs nearly 100,000 people and has an annual budget of approximately $150 billion. It consists of 16 agencies, including the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, the Food and Nutrition Service, and the Forest Service. The bulk of the department’s budget goes towards mandatory programs that provide services required by law, such as programs designed to provide nutrition assistance, promote agricultural exports, and conserve our environment.

The USDA also plays an important role in overseas aid programs by providing surplus foods to developing countries.

The United States Secretary of Agriculture administers the USDA.

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE

The Department of Commerce is the government agency tasked with creating the conditions for economic growth and opportunity.

The department supports U.S. business and industry through a number of services, including gathering economic and demographic data, issuing patents and trademarks, improving understanding of the environment and oceanic life, and ensuring the effective use of scientific and technical resources. The agency also formulates telecommunications and technology policy, and promotes U.S. exports by assisting and enforcing international trade agreements.

The United States Secretary of Commerce oversees a $8.9 billion budget and more than 41,000 employees.

DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE

The mission of the Department of Defense (DOD) is to provide the military forces needed to deter war and to protect the security of our country. The department’s headquarters is at the Pentagon.

The DOD consists of the Departments of the Army, Navy, and Air Force, as well as many agencies, offices, and commands, including the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Pentagon Force Protection Agency, the National Security Agency, and the Defense Intelligence Agency. The DOD occupies the vast majority of the Pentagon building in Arlington, Virginia.

The DOD is the largest government agency, with more than 1.4 million men and women on active duty, more than 700,000 civilian personnel, and 1.1 million citizens who serve in the National Guard and Reserve forces. Together, the military and civilian arms of DOD protect national interests through war-fighting, providing humanitarian aid, and performing peacekeeping and disaster relief services.

DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION

The mission of the Department of Education is to promote student learning and preparation for college, careers, and citizenship in a global economy by fostering educational excellence and ensuring equal access to educational opportunity.

The Department administers federal financial aid for higher education, oversees educational programs and civil rights laws that promote equity in student learning opportunities, collects data and sponsors research on America’s schools to guide improvements in education quality, and works to complement the efforts of state and local governments, parents, and students.

The U.S. Secretary of Education oversees the Department’s 4,200 employees and $68.6 billion budget.

DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY

The mission of the Department of Energy (DOE) is to advance the national, economic, and energy security of the United States.

The DOE promotes America’s energy security by encouraging the development of reliable, clean, and affordable energy. It administers federal funding for scientific research to further the goal of discovery and innovation — ensuring American economic competitiveness and improving the quality of life for Americans. The DOE is also tasked with ensuring America’s nuclear security, and with protecting the environment by providing a responsible resolution to the legacy of nuclear weapons production.

The United States Secretary of Energy oversees a budget of approximately $23 billion and more than 100,000 federal and contract employees.

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is the United States government’s principal agency for protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services, especially for those who are least able to help themselves. Agencies of HHS conduct health and social science research, work to prevent disease outbreaks, assure food and drug safety, and provide health insurance.

In addition to administering Medicare and Medicaid, which together provide health coverage to one in four Americans, HHS also oversees the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control.

The Secretary of Health and Human Services oversees a budget of approximately $700 billion and approximately 65,000 employees. The Department’s programs are administered by 11 operating divisions, including eight agencies in the U.S. Public Health Service, two human services agencies, and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) protects the American people from a wide range of foreign and domestic threats. DHS has a broad and diverse mission set, including to prevent and disrupt terrorist attacks, protect critical infrastructure and civilian computer networks, facilitate lawful trade and travel, respond to and recover from natural disasters, protect our borders, and regulate the migration of individuals to and from our country.

The third largest Cabinet department, DHS employs more than 250,000 people and deploys an $58 billion annual budget across more than 20 components, including the U.S. Secret Service, Transportation Security Administration, Federal Emergency Management Agency, U.S. Coast Guard, U. S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. The Homeland Security Act of 2002 established the Department in response to the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001 and brought together 22 executive branch agencies.

The Assistant to the President for Homeland Security and the Secretary of Homeland Security coordinate policy, including through the Homeland Security Council at the White House and in cooperation with other defense and intelligence agencies.

DEPARTMENT OF HOUSING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) is the federal agency responsible for national policies and programs that address America’s housing needs, improve and develop the nation’s communities, and enforce fair housing laws. The Department plays a major role in supporting homeownership for low- and moderate-income families through its mortgage insurance and rent subsidy programs.

Offices within HUD include the Federal Housing Administration, which provides mortgage and loan insurance; the Office of Fair Housing and Equal Opportunity, which ensures all Americans equal access to the housing of their choice; and the Community Development Block Grant Program, which helps communities with economic development, job opportunities, and housing rehabilitation. HUD also administers public housing and homeless assistance.

The Secretary of Housing and Urban Development oversees more than 9,000 employees with a budget of approximately $40 billion.

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

The Department of the Interior (DOI) is the nation’s principal conservation agency. Its mission is to protect America’s natural resources, offer recreation opportunities, conduct scientific research, conserve and protect fish and wildlife, and honor the U.S. government’s responsibilities to American Indians, Alaskan Natives, and to island communities.

DOI manages approximately 500 million acres of surface land, or about one-fifth of the land in the United States, and manages hundreds of dams and reservoirs. Agencies within the DOI include the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Fish and Wildlife Service, and the U.S. Geological Survey. The DOI manages the national parks and is tasked with protecting endangered species.

The Secretary of the Interior oversees about 70,000 employees and 200,000 volunteers on a budget of approximately $16 billion. Every year it raises billions in revenue from energy, mineral, grazing, and timber leases, as well as recreational permits and land sales.

DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE

The mission of the Department of Justice (DOJ) is to enforce the law and defend the interests of the United States according to the law; to ensure public safety against threats foreign and domestic; to provide federal leadership in preventing and controlling crime; to seek just punishment for those guilty of unlawful behavior; and to ensure fair and impartial administration of justice for all Americans.

The DOJ is made up of 40 component organizations, including the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the U.S. Marshals, and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. The Attorney General is the head of the DOJ and chief law enforcement officer of the federal government. The Attorney General represents the United States in legal matters, advises the President and the heads of the executive departments of the government, and occasionally appears in person before the Supreme Court.

With a budget of approximately $25 billion, the DOJ is the world’s largest law office and the central agency for the enforcement of federal laws.

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

The Department of Labor oversees federal programs for ensuring a strong American workforce. These programs address job training, safe working conditions, minimum hourly wage and overtime pay, employment discrimination, and unemployment insurance.

The Department of Labor’s mission is to foster and promote the welfare of the job seekers, wage earners, and retirees of the United States by improving their working conditions, advancing their opportunities for profitable employment, protecting their retirement and health care benefits, helping employers find workers, strengthening free collective bargaining, and tracking changes in employment, prices, and other national economic measurements.

Offices within the Department of Labor the Occupational Safety & Health Administration, which promotes the safety and health of America’s working men and women, and the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the federal government’s principal statistics agency for labor economics, and.

The Secretary of Labor oversees 15,000 employees on a budget of approximately $12 billion.

DEPARTMENT OF STATE

The Department of State plays the lead role in developing and implementing the President’s foreign policy. Major responsibilities include United States representation abroad, foreign assistance, foreign military training programs, countering international crime, and a wide assortment of services to U.S. citizens and foreign nationals seeking entrance to the United States.

The U.S. maintains diplomatic relations with approximately 180 countries — each posted by civilian U.S. Foreign Service employees — as well as with international organizations. At home, more than 5,000 civil employees carry out the mission of the Department.

The Secretary of State serves as the President’s top foreign policy adviser, and oversees 30,000 employees and a budget of approximately $35 billion.

DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION

The mission of the Department of Transportation (DOT) is to ensure a fast, safe, efficient, accessible and convenient transportation system that meets our vital national interests and enhances the quality of life of the American people.

Organizations within the DOT include the Federal Highway Administration, the Federal Aviation Administration, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, the Federal Transit Administration, the Federal Railroad Administration and the Maritime Administration.

The U.S. Secretary of Transportation oversees nearly 55,000 employees and a budget of approximately $70 billion.

DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY

The Department of the Treasury is responsible for promoting inclusive economic prosperity for all Americans.

The Department advances U.S. and global economic growth to raise American standards of living, support communities, promote racial justice, combat climate change, and foster financial stability. The Department operates systems that are critical to the nation’s financial infrastructure, such as the production of coin and currency, the disbursement of payments owed to the American public, the collection of necessary taxes, and the borrowing of funds required by congressional enactments to run the federal government. The Treasury Department also performs a critical role in enhancing national security by safeguarding our financial systems, implementing economic sanctions against foreign threats to the U.S., and identifying and targeting financial support networks that threaten our national security.

The Secretary of the Treasury oversees a budget of approximately $13 billion and a staff of more than 100,000 employees.

DEPARTMENT OF VETERANS AFFAIRS

The Department of Veterans Affairs is responsible for administering benefit programs for veterans, their families, and their survivors. These benefits include pension, education, disability compensation, home loans, life insurance, vocational rehabilitation, survivor support, medical care, and burial benefits. Veterans Affairs became a cabinet-level department in 1989.

Of the 25 million veterans currently alive, nearly three of every four served during a war or an official period of hostility. About a quarter of the nation’s population — approximately 70 million people — are potentially eligible for V.A. benefits and services because they are veterans, family members, or survivors of veterans.

The Secretary of Veterans Affairs oversees a budget of approximately $90 billion and a staff of approximately 235,000 employees.