Summary

This post on Work Visas is 1 of 3 issues that US onAir curators are focusing on in the Immigration category.

A citizen of a foreign country who wishes to work in the United States must first get the right visa. If the employment is for a fixed period, the applicant can apply for a temporary employment visa. There are 11 temporary worker visa categories. Most applicants for temporary worker visas must have an approved petition. The prospective employer must file the petition on behalf of the applicant. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) reviews the petition.

Source: Dept. of State

OnAir Post: Work Visas

News

PBS NewsHour – May 20, 2021 (08:10)

President Joe Biden has said that changing immigration law remains an important piece of his agenda. But the path to new legislation is complex and hardly clear. One of the biggest flashpoints in this debate are questions about undocumented workers and their role in the economy. Paul Solman dives into those questions for his latest report for “Making Sense.”

About

Check the Immigration post for the party positions, committees, government agencies related to Work Visas issues.

Challenges

Limited Availability of Visas:

- Annual caps or quotas for certain visa types (e.g., H-1B, H-2B) create competition and delays in obtaining visas.

2. Complex and Time-Consuming Process:

- Application forms, supporting documents, and extensive background checks can make the process lengthy and burdensome.

3. Employer Sponsorship Requirement:

- Most work visas require an employer willing to sponsor and financially support the foreign worker, which can limit options.

4. H-1B Visa Reforms Debate:

- Controversies over the H-1B program, including concerns about outsourcing and wage suppression, have led to proposed reforms that could impact availability.

5. Backlogs and Delays:

- High demand for work visas has resulted in significant delays in processing and adjudications, leading to uncertainty for employers and workers.

6. Security Concerns:

- Enhanced security measures following terrorist attacks have increased scrutiny of work visa applicants, potentially leading to delays and denials.

7. Political and Economic Climate:

- Changes in immigration policies and economic conditions can impact the availability, issuance, and enforcement of work visas.

8. Employer Compliance:

- Employers must adhere to specific regulations and reporting requirements for sponsoring foreign workers, which can pose challenges for businesses.

9. Cultural and Language Barriers:

- Foreign workers may face cultural and language challenges adapting to the U.S. workplace, requiring support and training.

10. Limited Pathways to Permanent Residency:

- Many work visas do not offer a direct path to permanent residency, which can limit the long-term options for foreign workers in the U.S.

Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation

Solutions

Increase Visa Quotas and Processing Capacity:

- Increase the annual cap on H-1B and other work visas to meet the demand for skilled foreign workers.

- Streamline application processing and reduce backlogs by increasing staffing and technology at USCIS.

2. Expand Visa Categories and Eligibility:

- Create new visa categories for emerging professions and start-up entrepreneurs.

- Expand the definition of “specialty occupation” to include a broader range of high-skilled jobs.

3. Promote Portability and Flexibility:

- Allow H-1B visa holders to change employers without having to go through a new petition process.

- Extend the duration of work visas for STEM professionals and entrepreneurs.

4. Encourage Employer-Driven Immigration Reform:

- Provide incentives for businesses to hire and retain foreign workers.

- Streamline the employer-sponsored green card process to prevent skilled workers from leaving the US.

5. Enhance STEM Education and Workforce Development:

- Invest in programs that encourage STEM education and workforce training for US citizens.

- Partner with educational institutions and businesses to develop pipelines for qualified workers.

6. Address Underlying Economic Factors:

- Examine economic trends and policies that contribute to the need for foreign workers.

- Identify and address any barriers to domestic worker recruitment and training.

7. Implement Technology and Efficiency Measures:

- Digitize and automate visa application processes to reduce manual labor and processing times.

- Utilize artificial intelligence and machine learning to streamline case reviews.

8. Foster International Collaboration and Partnerships:

- Engage with foreign governments and educational institutions to facilitate the exchange of skilled workers.

- Develop reciprocal agreements to promote mobility and address global talent shortages.

9. Promote Public Understanding and Education:

- Educate the public about the benefits and challenges of work visas.

- Address misconceptions and dispel myths surrounding skilled immigration.

10. Regular Review and Evaluation:

- Establish mechanisms for regular review of work visa policies and procedures.

- Evaluate the impact of changes and make necessary adjustments to ensure an effective and efficient system.

Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation

Websites

USCIS Websites:

Department of State Websites:

Other Government Resources:

Visa Processing Services:

Information and Resources:

Note: It is important to consult with an immigration attorney or licensed visa professional for specific guidance and assistance.

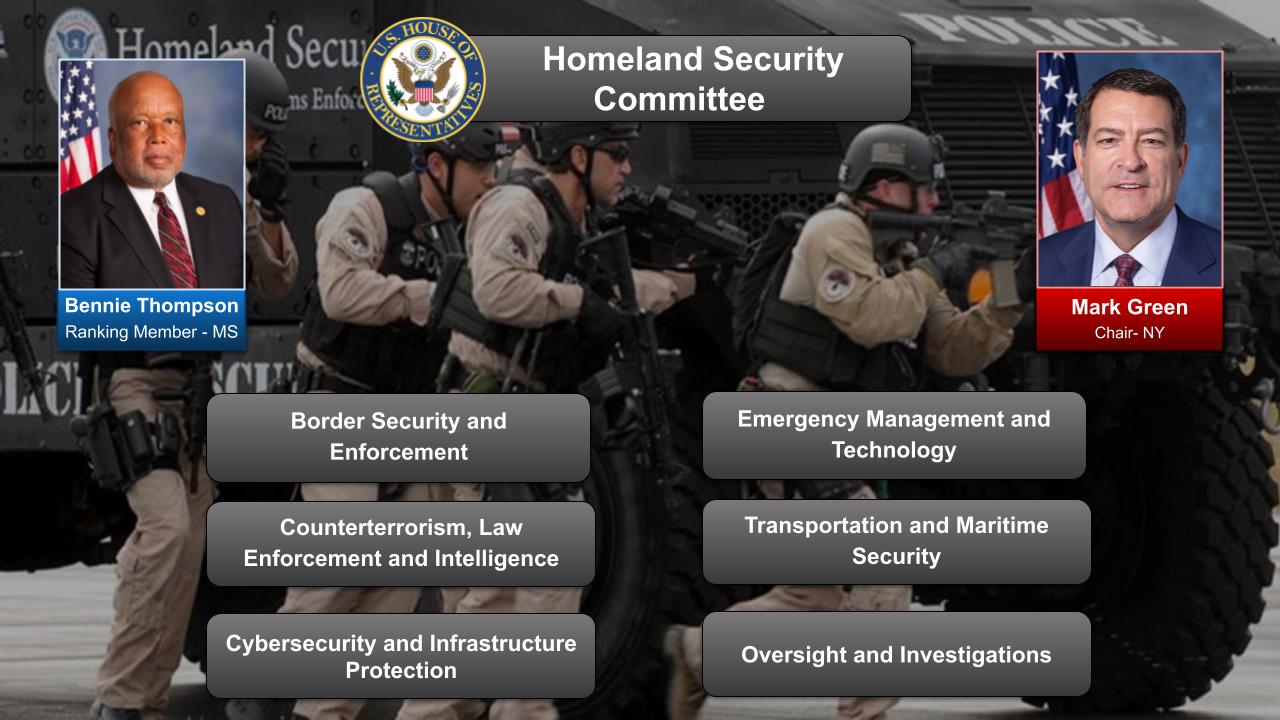

Source: Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation American Competitiveness in the Twenty-First Century Act (AC21) 2. Temporary Worker Visa Improvement and Responsibility Act (TWIRVA) 3. H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2004 4. Secure Fence Act of 2006 5. American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 6. Border Security, Economic Opportunity, and Immigration Modernization Act of 2013 7. Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Sampling of Bills H.R.6542 — Immigration Visa Efficiency and Security Act of 2023 S.979 — H–1B and L–1 Visa Reform Act of 2023 H.R.7028 —Keeping Our Promise Act H.R.3194 — U.S. Citizenship Act H-1B Visa Reform Act of 2023 (H.R. 987) 2. Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act of 2023 (S. 386) 3. American Competitiveness and Workforce Improvement Act of 2023 (H.R. 1044) 4. H-1B and L-1 Visa Fraud Prevention Act of 2023 (H.R. 1390) 5. STEM OPT Extension Act of 2023 (S. 670) 6. Green Card For STEM Graduates Act of 2023 (H.R. 2873) 7. Visa Sponsorship Reform Act of 2023 (S. 2168) Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation House of Representatives: Senate: Joint Committees: Other Relevant Committees: Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Source: Government Website USCIS upholds America’s promise as a nation of welcome and possibility with fairness, integrity, and respect for all we serve. USCIS is the government agency that oversees lawful immigration to the United States. We are 21,000 government employees and contractors working at more than 200 offices across the world. Champion People – In Service to the Public People are at the heart of our mission – from USCIS employees to the people we serve. We value our employees and empower them to bring their best selves to USCIS, in service to the public and the USCIS mission. When people of all backgrounds are valued, heard, and respected in an inclusive manner, the nation reaps the reward. Uphold Integrity – Honor of Character and Action Integrity is the foundation for trust and strengthens the American public’s confidence in the immigration system. USCIS maintains the highest professional standards in the decisions we make, the processes we create, and the relationships we build. We achieve excellence by vigilantly carrying out the USCIS mission. Foster Collaboration – Moving Forward Together Strong teams build strong organizations that deliver quality results. Creativity and innovation are cultivated when employees feel confident proposing new ideas, giving and receiving feedback, and collaborating with colleagues, stakeholders, and the communities we serve. The success of our mission is tied to the quality of our partnerships and teamwork. Advance Opportunity – The Future Depends on What We Do Today At USCIS, we believe that every task we face is an opportunity to promote career development, inclusivity, and equity. We are committed to growing the talents of our employees to serve our mission, our nation, and those who seek to reunify with their families, contribute their talents, seek refuge, or become our newest U.S. citizens. Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation The H-1B Visa Program 2. The H-2B Visa Program 3. The L-1 Visa Program 4. The OPT (Optional Practical Training) Program 5. The STEM OPT Extension Program 6. The STEM Workforce for America Act (SWA) 7. The American Competitiveness in the 21st Century Act (AC21) 8. The National Science and Engineering Council (NSERC) 9. The STEM Education Coalition 10. The Computer Science for All (CSforAll) Initiative Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Democratic Organizations Republican Organizations U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS)[3] is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that administers the country’s naturalization and immigration system. It is a successor to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was dissolved by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and replaced by three components within the DHS: USCIS, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). USCIS performs many of the duties of the former INS, namely processing and adjudicating various immigration matters, including applications for work visas, asylum, and citizenship. Additionally, the agency is officially tasked with safeguarding national security, maintaining immigration case backlogs, and improving efficiency. Ur Jaddou has been the director of USCIS since August 3, 2021. USCIS processes immigrant visa petitions, naturalization applications, asylum applications, applications for adjustment of status (green cards), and refugee applications. It also makes adjudicative decisions performed at the service centers, and manages all other immigration benefits functions (i.e., not immigration enforcement) performed by the former INS. The USCIS’s other responsibilities include: While core immigration benefits functions remain the same as under the INS, a new goal is to process immigrants’ applications more efficiently. Improvement efforts have included attempts to reduce the applicant backlog and providing customer service through different channels, including the USCIS Contact Center with information in English and Spanish, Application Support Centers (ASCs), the Internet, and other channels. Enforcement of immigration laws remains under Customs and Border Protection (CBP) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). USCIS focuses on two key points on the immigrant’s path to civic integration: when they first become permanent residents and when they are ready to begin the formal naturalization process. A lawful permanent resident is eligible to become a U.S. citizen after holding the Permanent Resident Card for at least five continuous years, with no trips out of the country of 180 days or more.[4] If the lawful permanent resident marries a U.S. citizen, eligibility for U.S. citizenship is shortened to three years so long as the resident has been living with their spouse continuously for at least three years and the spouse has been a resident for at least three years.[5] USCIS handles all forms and processing materials related to immigration and naturalization. This is evident from USCIS’s predecessor, the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service), which is defunct as of March 1, 2003.[6][circular reference] USCIS handles two kinds of forms: those related to immigration, and those related to naturalization. Forms are designated by a specific name, and an alphanumeric sequence consisting of a letter followed by two or three digits. Forms related to immigration are designated with an I (for example, I-551, Permanent Resident Card) and forms related to naturalization are designated by an N (for example, N-400, Application for Naturalization). 1 Ken Cuccinelli served from July 8 to December 31, 2019, as de facto Acting Director. His tenure as Acting Director was ruled unlawful. He remained Principal Deputy Director at USCIS for the remainder of his tenure. The United States immigration courts, immigration judges, and the Board of Immigration Appeals, which hears appeals from them, are part of the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) within the United States Department of Justice. (USCIS is part of the Department of Homeland Security.)[7] USCIS’s official website was redesigned in 2009 and unveiled on September 22, 2009.[8] The last major redesign before 2009 was in October 2006. The website now includes a virtual assistant, Emma, who answers questions in English and Spanish.[9] USCIS’s website contains self-service tools, including a case status checker and address change request form. Applicants, petitioners, and their authorized representatives can also submit case inquiries and service requests on USCIS’s website. The inquiries and requests are routed to the relevant USCIS center or office to process. Case inquiries may involve asking about a case that is outside of normal expected USCIS processing times for the form. Inquiries and service requests may also concern not receiving a notice, card, or document by mail, correcting typographical errors, and requesting disability accommodations.[10] If the self-service tools on USCIS’s website cannot resolve an issue, the applicant, petitioner, or authorized representative can contact the USCIS Contact Center. If the Contact Center cannot assist the inquirer directly, the issue will be forwarded to the relevant USCIS center or office for review. Some applicants and petitioners, primarily those who are outside of the United States, may also schedule appointments on USCIS’s website Unlike most other federal agencies, USCIS is funded almost entirely by user fees, most of it via the Immigration Examinations Fee Account (IEFA).[11] USCIS is authorized to collect fees for its immigration case adjudication and naturalization services by the Immigration and Nationality Act.[12] In fiscal year 2020, USCIS had a budget of US$4.85 billion; 97.3% of it was funded by fees and 2.7% by congressional appropriations.[13] USCIS consists of approximately 19,000 federal employees and contractors working at 223 offices around the world.[14] A Field USCIS office provides Interviews for all non-asylum cases; Naturalization ceremonies; Appointments for information and applicant services. [1] USCIS Asylum offices scheduled interviews only for asylum and suspension of deportation and special rule cancellation of removal under Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA). Asylum Offices do not provide information services. Applications are not filed at Asylum Offices. [2] International Offices provide services to U.S. citizens, permanent residents of the United States, and certain other people who are visiting or residing outside the United States. International Offices are in China – Beijing & Guangzhou, Cuba- Havana, El Salvador – San Salvador, Guatemala – Guatemala City, Honduras – Tegucigalpa City, India – New Delhi, Kenya – Nairobi, Mexico – Mexico City. [3] To find your local office you can visit https://www.uscis.gov/about-us/find-a-uscis-office USCIS’s mission statement was changed on February 9, 2022. USCIS Director Jaddou announced the new mission statement. In 2021, USCIS leadership empowered employees to submit words that they felt best illustrated the agency’s work. The new mission statement reflects this feedback from the workforce, the Biden administration’s priorities, and Jaddou’s vision for an inclusive and accessible agency.[15] The mission statement now reads: USCIS upholds America’s promise as a nation of welcome and possibility with fairness, integrity, and respect for all we serve.[16] Legislation

Laws

New Bills Introduced 2023-2024

Sponsor: McCormick, Richard [Rep.-R-GA-6] (Introduced 12/01/2023)

Cosponsors: (24)

Committees: House – Judiciary

Latest Action: House – 12/01/2023 Referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary.

Sponsor: Durbin, Richard J. [Sen.-D-IL] (Introduced 03/27/2023)

Cosponsors: (5)

Committees: Senate – Judiciary

Latest Action: Senate – 03/27/2023 Read twice and referred to the Committee on the Judiciary. (text: CR S957-964)

Sponsor: Torres, Ritchie [Rep.-D-NY-15] (Introduced 01/17/2024)

Cosponsors: (72)

Committees: House – Judiciary

Latest Action: House – 01/17/2024 Referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary.

Sponsor: Sánchez, Linda T. [Rep.-D-CA-38] (Introduced 05/10/2023)

Cosponsors: (116)

Committees: House – Judiciary; Ways and Means; Armed Services; Education and the Workforce; House Administration; Financial Services; Natural Resources; Oversight and Accountability; Foreign Affairs; Homeland Security; Intelligence (Permanent Select); Energy and Commerce

Latest Action: House – 06/07/2023 Referred to the Subcommittee on the Central Intelligence Agency.Committees, Agencies, & Programs

Committees

Government Agencies

US Citizenship and Immigration Services

Mission Statement

Who We Are

Core Values

Resources

External Links

Programs & Initiatives

More Information

Nonpartisan Organizations

Partisan Organizations

“USCIS” (Wiki)

Contents

United States citizenship and immigration ![]()

Immigration Citizenship Agencies Legislation History Relevant legislation ![]() United States portal

United States portalFunctions

Forms

List of directors of the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services

No. Portrait Director Took office Left office Time in office Party President 1 Eduardo Aguirre

(born 1946)August 15, 2003 June 16, 2005 1 year, 305 days Republican George W. Bush (R) – Michael Petrucelli

ActingJune 17, 2005 July 25, 2005 38 days ? George W. Bush (R) 2 Emilio T. Gonzalez

(born 1956)December 21, 2005 April 18, 2008 2 years, 119 days Republican George W. Bush (R) – Jonathan “Jock” Scharfen

ActingApril 21, 2008 December 2, 2008 225 days ? George W. Bush (R) 3 Alejandro Mayorkas

(born 1959)August 12, 2009 December 23, 2013 4 years, 133 days Democratic Barack Obama (D) – Lori Scialabba

ActingDecember 23, 2013 July 9, 2014 198 days ? Barack Obama (D) 4 León Rodríguez

(born 1962)July 9, 2014 January 20, 2017 2 years, 195 days Democratic Barack Obama (D) – Lori Scialabba

ActingJanuary 20, 2017 March 31, 2017 70 days ? Donald Trump (R) – James W. McCament

ActingMarch 31, 2017 October 8, 2017 191 days ? Donald Trump (R) 5 L. Francis Cissna

(born 1966)October 8, 2017 June 1, 2019 1 year, 236 days Independent Donald Trump (R) – Ken Cuccinelli[1]

(born 1968)

ActingJune 10, 2019 November 18, 2019 161 days Republican Donald Trump (R) – Mark Koumans

ActingNovember 18, 2019 February 20, 2020 94 days Independent Donald Trump (R) – Joseph Edlow

ActingFebruary 20, 2020 January 20, 2021 335 days Independent Donald Trump (R) – Tracy Renaud

ActingJanuary 20, 2021 August 3, 2021 195 days Independent Joe Biden (D) 6 Ur Mendoza Jaddou

(born 1974)August 3, 2021 Incumbent 2 years, 270 days Independent Joe Biden (D) Immigration courts and judges

Operations

Internet presence

Inquiry and issue resolution

Funding

Staffing

Offices

Mission statement

See also

Comparable international agencies

References

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Homeland Security.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the United States Department of Homeland Security.External links

![]()

![Ken Cuccinelli[1]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ab/Ken_Cuccinelli_official_photo.jpg/100px-Ken_Cuccinelli_official_photo.jpg)