Summary

Go here to see all posts related to the Jan 6 committee, its hearings, and members.

Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol:

To investigate and report upon the facts, circumstances, and causes relating to the January 6, 2021, domestic terrorist attack upon the United States Capitol Complex (hereafter referred to as the “domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol”) and relating to the interference with the peaceful transfer of power

Democratic Members (Majority):

Bennie Thompson, Mississippi, Chair

Zoe Lofgren, California

Adam Schiff, California

Pete Aguilar, California

Stephanie Murphy, Florida

Jamie Raskin, Maryland

Elaine Luria, Virginia

Republican Members (Minority):

Liz Cheney, Wyoming

Adam Kinzinger, Illinois

Featured Video:

Jan. 6 House Select Committee Holds First Hearing On Capitol Riot – July 22, 2021

OnAir Post: Jan 6 Committee

News

The House committee investigating the Jan. 6 attack will hold its third public hearing June 16, focused on former President Donald Trump’s efforts to pressure former Vice President Mike Pence to reject Congress’ official count of Electoral College votes on the day of the attack. The hearing is scheduled to begin at 1 p.m. ET on Thursday, June 16. The vice president is charged with overseeing the Electoral College vote count — already certified by individual states — in a joint session of Congress following a presidential election. Trump called on Pence repeatedly to reject the results confirming President Joe Biden’s win, telling supporters in a rally hours before the attack that “it will be a sad day for the country” if his vice president did not come through. Pence said in a statement after the speech he did not have the constitutional authority to do what the president asked. Some rioters began chanting “hang Mike Pence.” Committee member Rep. Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., said at the start of the hearings that upon hearing this, Trump said “maybe our supporters have the right idea.” The committee postponed a hearing scheduled for June 15 that was meant to focus on Trump’s efforts to replace Attorney General Bill Barr, who did not support his claims of voter fraud after the election. Members of the committee said this week they thought they had evidence to indict Trump for seeking to overturn the results of the 2020 election, which they will lay out as part of several public hearings this month.

June 13, 2022 – 12:00 am to 12:49 pm (ET)

The House panel investigating the Jan. 6 insurrection presents more of its findings to the public on Monday, June 13. The hearing, the second of several planned by the Jan. 6 committee in the coming weeks, will focus on former President Donald Trump’s level of involvement leading up to and on the day of the attack on the Capitol.

Donald Trump’s closest campaign advisers, top government officials and even his family were dismantling his false claims of 2020 election fraud ahead of Jan. 6, but the defeated president seemed “detached from reality” and clinging to outlandish theories to stay in power, the committee investigating the Capitol attack was told Monday.

With gripping testimony, the panel is laying out in step by step fashion how Trump ignored his own campaign team’s data as one state after another flipped to Joe Biden, and instead latched on to conspiracy theories, court cases and his own declarations of victory rather than having to admit defeat.

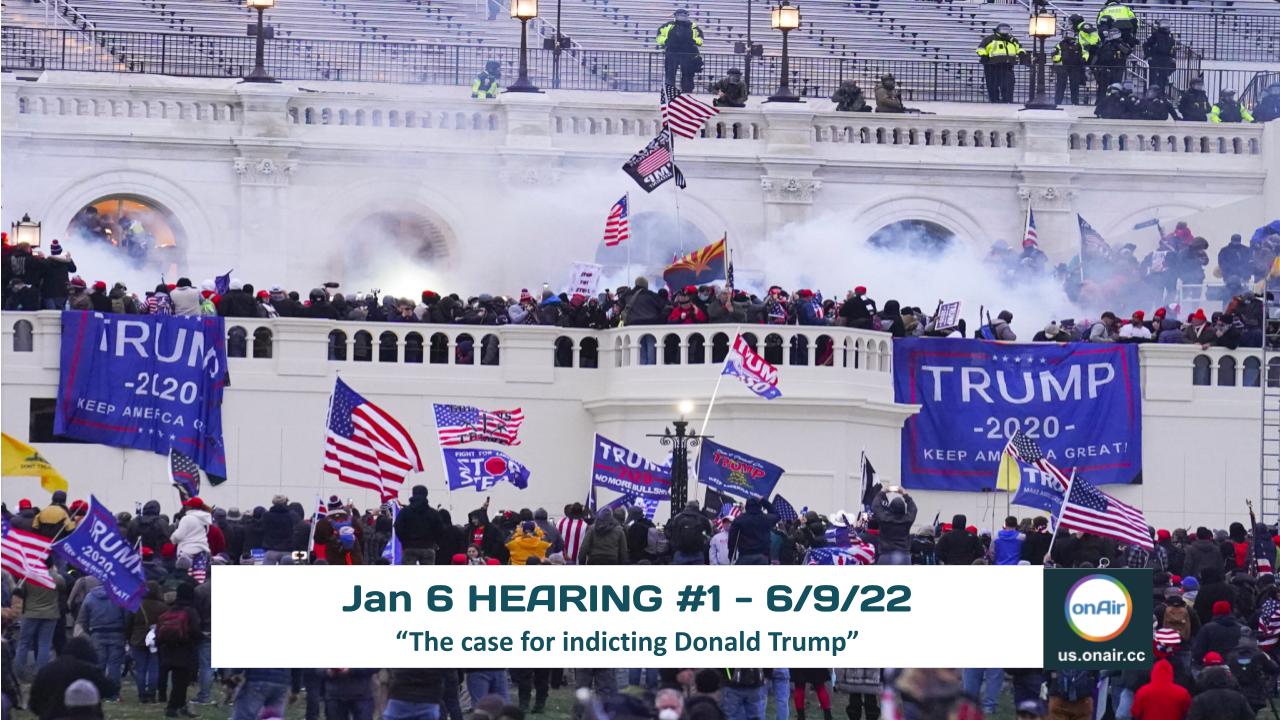

Trump’s “big lie” of election fraud escalated and transformed into marching orders that summoned supporters to Washington and then sent them to the Capitol on Jan. 6 to block Biden’s victory.

“He’s become detached from reality if he really believes this stuff,” testified former Attorney General William Barr in his interview with the committee.

PBS NewsHour, June 9, 2022 – 6:00 pm to 10:00 pm (ET)

PBS NewsHour – June 10, 2022 (33:15)

PBS NewsHour – June 10, 2022 (14:05)

Press Release – August 27, 2021

Bolton, MS—Today, Chairman Bennie G. Thompson announced that the Select Committee is demanding records related to the January 6th violent attack on the U.S. Capitol from 15 social media companies. In letters to the companies, Chairman Thompson seeks information including records related to the spread of misinformation, efforts to overturn the 2020 election or prevent the certification of the results, domestic violent extremism, and foreign influence in the 2020 election. Chairman Thompson set a two-week deadline for the companies to produce records.

This expansion of the Select Committee’s probe comes on the heels of Wednesday’s demands for records from eight Executive Branch agencies. It also follows the July 27 hearing at which four police officers testified about their experiences on January 6th defending the U.S. Capitol in the face of a violent mob aiming to derail the peaceful transfer of power. The officers’ call to action underscored the importance of the Select Committee’s mandate to uncover the facts about January 6th and its causes and to help ensure such an attack on American democracy cannot happen again.

“The Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol is examining the facts, circumstances, and causes of the attack and relating to the peaceful transfer of power, in order to identify and evaluate lessons learned and to recommend corrective laws, policies, procedures, rules, or regulations,” wrote Chairman Thompson.

The letters to the social media companies seek a range of records, including data, reports, analyses, and communications stretching back to spring of 2020. The Select Committee is also seeking information on policy changes social media companies adopted—or failed to adopt—to address the spread of false information, violent extremism, and foreign malign influence, including decisions on banning material from platforms and contacts with law enforcement and other government entities.

The following companies received record demands from the Select Committee:

About

Overview

Whereas January 6, 2021, was one of the darkest days of our democracy, during which insurrectionists attempted to impede Congress’s Constitutional mandate to validate the presidential election and launched an assault on the United States Capitol Complex that resulted in multiple deaths, physical harm to over 140 members of law enforcement, and terror and trauma among staff, institutional employees, press, and Members;

Whereas, on January 27, 2021, the Department of Homeland Security issued a National Terrorism Advisory System Bulletin that due to the “heightened threat environment across the United States,” in which “[S]ome ideologically-motivated violent extremists with objections to the exercise of governmental authority and the presidential transition, as well as other perceived grievances fueled by false narratives, could continue to mobilize to incite or commit violence.” The Bulletin also stated that—

(1) “DHS is concerned these same drivers to violence will remain through early 2021 and some DVEs [domestic violent extremists] may be emboldened by the January 6, 2021 breach of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. to target elected officials and government facilities.”; and

(2) “Threats of violence against critical infrastructure, including the electric, telecommunications and healthcare sectors, increased in 2020 with violent extremists citing misinformation and conspiracy theories about COVID–19 for their actions”;

Whereas, on September 24, 2020, Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation Christopher Wray testified before the Committee on Homeland Security of the House of Representatives that—

(1) “[T]he underlying drivers for domestic violent extremism – such as perceptions of government or law enforcement overreach, sociopolitical conditions, racism, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, misogyny, and reactions to legislative actions – remain constant.”;

(2) “[W]ithin the domestic terrorism bucket category as a whole, racially-motivated violent extremism is, I think, the biggest bucket within the larger group. And within the racially-motivated violent extremists bucket, people subscribing to some kind of white supremacist-type ideology is certainly the biggest chunk of that.”; and

(3) “More deaths were caused by DVEs than international terrorists in recent years. In fact, 2019 was the deadliest year for domestic extremist violence since the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995”;

Whereas, on April 15, 2021, Michael Bolton, the Inspector General for the United States Capitol Police, testified to the Committee on House Administration of the House of Representatives that—

(1) “The Department lacked adequate guidance for operational planning. USCP did not have policy and procedures in place that communicated which personnel were responsible for operational planning, what type of operational planning documents its personnel should prepare, nor when its personnel should prepare operational planning documents.”; and

(2) “USCP failed to disseminate relevant information obtained from outside sources, lacked consensus on interpretation of threat analyses, and disseminated conflicting intelligence information regarding planned events for January 6, 2021.”; and

Whereas the security leadership of the Congress under-prepared for the events of January 6th, with United States Capitol Police Inspector General Michael Bolton testifying again on June 15, 2021, that—

(1) “USCP did not have adequate policies and procedures for FRU (First Responder Unit) defining its overall operations. Additionally, FRU lacked resources and training for properly completing its mission.”;

(2) “The Department did not have adequate policies and procedures for securing ballistic helmets and vests strategically stored around the Capitol Complex.”; and

(3) “FRU did not have the proper resources to complete its mission.”: Now, therefore, be it

Resolved,

SECTION 1. ESTABLISHMENT.

There is hereby established the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol (hereinafter referred to as the “Select Committee”).

SEC. 2. COMPOSITION.

(a) Appointment Of Members.—The Speaker shall appoint 13 Members to the Select Committee, 5 of whom shall be appointed after consultation with the minority leader.

(b) Designation Of Chair.—The Speaker shall designate one Member to serve as chair of the Select Committee.

(c) Vacancies.—Any vacancy in the Select Committee shall be filled in the same manner as the original appointment.

SEC. 3. PURPOSES.

Consistent with the functions described in section 4, the purposes of the Select Committee are the following:

(1) To investigate and report upon the facts, circumstances, and causes relating to the January 6, 2021, domestic terrorist attack upon the United States Capitol Complex (hereafter referred to as the “domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol”) and relating to the interference with the peaceful transfer of power, including facts and causes relating to the preparedness and response of the United States Capitol Police and other Federal, State, and local law enforcement agencies in the National Capital Region and other instrumentalities of government, as well as the influencing factors that fomented such an attack on American representative democracy while engaged in a constitutional process.

(2) To examine and evaluate evidence developed by relevant Federal, State, and local governmental agencies regarding the facts and circumstances surrounding the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol and targeted violence and domestic terrorism relevant to such terrorist attack.

(3) To build upon the investigations of other entities and avoid unnecessary duplication of efforts by reviewing the investigations, findings, conclusions, and recommendations of other executive branch, congressional, or independent bipartisan or nonpartisan commission investigations into the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol, including investigations into influencing factors related to such attack.

SEC. 4. FUNCTIONS.

(a) Functions.—The functions of the Select Committee are to—

(1) investigate the facts, circumstances, and causes relating to the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol, including facts and circumstances relating to—

(A) activities of intelligence agencies, law enforcement agencies, and the Armed Forces, including with respect to intelligence collection, analysis, and dissemination and information sharing among the branches and other instrumentalities of government;

(B) influencing factors that contributed to the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol and how technology, including online platforms, financing, and malign foreign influence operations and campaigns may have factored into the motivation, organization, and execution of the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol; and

(C) other entities of the public and private sector as determined relevant by the Select Committee for such investigation;

(2) identify, review, and evaluate the causes of and the lessons learned from the domestic terrorist attack on the Capitol regarding—

(A) the command, control, and communications of the United States Capitol Police, the Armed Forces, the National Guard, the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, and other Federal, State, and local law enforcement agencies in the National Capital Region on or before January 6, 2021;

(B) the structure, coordination, operational plans, policies, and procedures of the Federal Government, including as such relate to State and local governments and nongovernmental entities, and particularly with respect to detecting, preventing, preparing for, and responding to targeted violence and domestic terrorism;

(C) the structure, authorities, training, manpower utilization, equipment, operational planning, and use of force policies of the United States Capitol Police;

(D) the policies, protocols, processes, procedures, and systems for the sharing of intelligence and other information by Federal, State, and local agencies with the United States Capitol Police, the Sergeants at Arms of the House of Representatives and Senate, the Government of the District of Columbia, including the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, the National Guard, and other Federal, State, and local law enforcement agencies in the National Capital Region on or before January 6, 2021, and the related policies, protocols, processes, procedures, and systems for monitoring, assessing, disseminating, and acting on intelligence and other information, including elevating the security posture of the United States Capitol Complex, derived from instrumentalities of government, open sources, and online platforms; and

(E) the policies, protocols, processes, procedures, and systems for interoperability between the United States Capitol Police and the National Guard, the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia, and other Federal, State, and local law enforcement agencies in the National Capital Region on or before January 6, 2021; and

(3) issue a final report to the House containing such findings, conclusions, and recommendations for corrective measures described in subsection (c) as it may deem necessary.

(b) Reports.—

(1) INTERIM REPORTS.—In addition to the final report addressing the matters in subsection (a) and section 3, the Select Committee may report to the House or any committee of the House from time to time the results of its investigations, together with such detailed findings and legislative recommendations as it may deem advisable.

(2) TREATMENT OF CLASSIFIED OR LAW ENFORCEMENT-SENSITIVE MATTER.—Any report issued by the Select Committee shall be issued in unclassified form but may include a classified annex, a law enforcement-sensitive annex, or both.

(c) Corrective Measures Described.—The corrective measures described in this subsection may include changes in law, policy, procedures, rules, or regulations that could be taken—

(1) to prevent future acts of violence, domestic terrorism, and domestic violent extremism, including acts targeted at American democratic institutions;

(2) to improve the security posture of the United States Capitol Complex while preserving accessibility of the Capitol Complex for all Americans; and

(3) to strengthen the security and resilience of the United States and American democratic institutions against violence, domestic terrorism, and domestic violent extremism.

(d) No Markup Of Legislation Permitted.—The Select Committee may not hold a markup of legislation.

SEC. 5. PROCEDURE.

(a) Access To Information From Intelligence Community.—Notwithstanding clause 3(m) of rule X of the Rules of the House of Representatives, the Select Committee is authorized to study the sources and methods of entities described in clause 11(b)(1)(A) of rule X insofar as such study is related to the matters described in sections 3 and 4.

(b) Treatment Of Classified Information.—Clause 11(b)(4), clause 11(e), and the first sentence of clause 11(f) of rule X of the Rules of the House of Representatives shall apply to the Select Committee.

(c) Applicability Of Rules Governing Procedures Of Committees.—Rule XI of the Rules of the House of Representatives shall apply to the Select Committee except as follows:

(1) Clause 2(a) of rule XI shall not apply to the Select Committee.

(2) Clause 2(g)(2)(D) of rule XI shall apply to the Select Committee in the same manner as it applies to the Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence.

(3) Pursuant to clause 2(h) of rule XI, two Members of the Select Committee shall constitute a quorum for taking testimony or receiving evidence and one-third of the Members of the Select Committee shall constitute a quorum for taking any action other than one for which the presence of a majority of the Select Committee is required.

(4) The chair of the Select Committee may authorize and issue subpoenas pursuant to clause 2(m) of rule XI in the investigation and study conducted pursuant to sections 3 and 4 of this resolution, including for the purpose of taking depositions.

(5) The chair of the Select Committee is authorized to compel by subpoena the furnishing of information by interrogatory.

(6) (A) The chair of the Select Committee, upon consultation with the ranking minority member, may order the taking of depositions, including pursuant to subpoena, by a Member or counsel of the Select Committee, in the same manner as a standing committee pursuant to section 3(b)(1) of House Resolution 8, One Hundred Seventeenth Congress.

(B) Depositions taken under the authority prescribed in this paragraph shall be governed by the procedures submitted by the chair of the Committee on Rules for printing in the Congressional Record on January 4, 2021.

(7) Subpoenas authorized pursuant to this resolution may be signed by the chair of the Select Committee or a designee.

(8) The chair of the Select Committee may, after consultation with the ranking minority member, recognize—

(A) Members of the Select Committee to question a witness for periods longer than five minutes as though pursuant to clause 2(j)(2)(B) of rule XI; and

(B) staff of the Select Committee to question a witness as though pursuant to clause 2(j)(2)(C) of rule XI.

(9) The chair of the Select Committee may postpone further proceedings when a record vote is ordered on questions referenced in clause 2(h)(4) of rule XI, and may resume proceedings on such postponed questions at any time after reasonable notice. Notwithstanding any intervening order for the previous question, an underlying proposition shall remain subject to further debate or amendment to the same extent as when the question was postponed.

(10) The provisions of paragraphs (f)(1) through (f)(12) of clause 4 of rule XI shall apply to the Select Committee.

SEC. 6. RECORDS; STAFF; TRAVEL; FUNDING.

(a) Sharing Records Of Committees.—Any committee of the House of Representatives having custody of records in any form relating to the matters described in sections 3 and 4 shall provide copies of such records to the Select Committee not later than 14 days of the adoption of this resolution or receipt of such records. Such records shall become the records of the Select Committee.

(b) Staff.—The appointment and the compensation of staff for the Select Committee shall be subject to regulations issued by the Committee on House Administration.

(c) Detail Of Staff Of Other Offices.—Staff of employing entities of the House or a joint committee may be detailed to the Select Committee to carry out this resolution and shall be deemed to be staff of the Select Committee.

(d) Use Of Consultants Permitted.—Section 202(i) of the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1946 (2 U.S.C. 4301(i)) shall apply with respect to the Select Committee in the same manner as such section applies with respect to a standing committee of the House of Representatives.

(e) Travel.—Clauses 8(a), (b), and (c) of rule X of the Rules of the House of Representatives shall apply to the Select Committee.

(f) Funding; Payments.—There shall be paid out of the applicable accounts of the House of Representatives such sums as may be necessary for the expenses of the Select Committee. Such payments shall be made on vouchers signed by the chair of the Select Committee and approved in the manner directed by the Committee on House Administration. Amounts made available under this subsection shall be expended in accordance with regulations prescribed by the Committee on House Administration.

SEC. 7. TERMINATION AND DISPOSITION OF RECORDS.

(a) Termination.—The Select Committee shall terminate 30 days after filing the final report under section 4.

(b) Disposition Of Records.—Upon termination of the Select Committee—

(1) the records of the Select Committee shall become the records of such committee or committees designated by the Speaker; and

(2) the copies of records provided to the Select Committee by a committee of the House under section 6(a) shall be returned to the committee.

Source: Committee website

Contact

Email: https://january6th.house.gov/tip-line

Locations

Chair Bennie G. Thompson

2466 Rayburn HOB

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-5876

Fax: (202) 225-5898

Web Links

Legislation

Markups

Source: Committee website

Hearings

Source: Committee website

See Also

NPR on the Members

Source: NPR

Wikipedia

Contents

(Top)

1History

2Members

3Investigation

3.1Simultaneous investigations by the Justice Department

3.2Information received from Mark Meadows

3.3Obstacles

3.3.1Release of documents from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

3.3.2Republicans not testifying

3.3.3Secret Service, DHS and Pentagon text messages deleted

3.3.4Trump funding legal defense of Republican witnesses

3.3.5Republican National Committee (RNC) claiming committee is illegitimate

4Public findings

5Final report

6Timeline of proceedings

7Subpoenas

8Reactions

9Notes

10References

11External links

The United States House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol (commonly referred to as the January 6th Committee) was a select committee of the U.S. House of Representatives established to investigate the U.S. Capitol attack.[1]

After refusing to concede the 2020 U.S. presidential election and perpetuating false and disproven claims of widespread voter fraud, then-President Donald Trump summoned a mob of protestors to the Capitol as the electoral votes were being counted on January 6, 2021. During the House Committee’s subsequent investigation, people gave sworn testimony that Trump knew he lost the election.[2] The Committee subpoenaed his testimony, identifying him as “the center of the first and only effort by any U.S. President to overturn an election and obstruct the peaceful transition of power”.[3] He sued the committee and never testified.[4][5]

On December 19, 2022, the Committee voted unanimously to refer Trump and the lawyer John Eastman to the U.S. Department of Justice for prosecution.[6] Recommended charges for Trump were obstruction of an official proceeding; conspiracy to defraud the United States; conspiracy to make a false statement; and attempts to “incite”, “assist” or “aid or comfort” an insurrection.[7] Obstruction and conspiracy to defraud were also the recommended charges for Eastman.[8]

Some members of Trump’s inner circle had cooperated with the committee, while others defied it.[9] For refusing to testify:

- Steve Bannon and Peter Navarro were convicted of contempt of Congress. Each was sentenced to four months in prison,[10][11] and Navarro began his sentence in March 2024.[12]

- Mark Meadows and Dan Scavino were also held in criminal contempt by Congress (but not prosecuted by DOJ).[13][14]

- Representatives McCarthy, Jordan, Biggs, and Perry were referred to the House Ethics Committee.[15]

The Committee interviewed over a thousand people[16] and reviewed over a million documents.[3] On December 22, 2022, it published an 845-page final report[17][18][19] (including the executive summary released three days earlier).[20] That week, the committee also began publishing interview transcripts.[21]

The committee was formed through a largely party-line vote on July 1, 2021, and it dissolved in early January 2023.[a][22] Its membership was a point of significant political contention. The only two House Republicans to vote to establish the Committee[23] were also the only two Republicans to serve on it: Liz Cheney and Adam Kinzinger.[b][24][25] The Republican National Committee censured them for their participation.[26]

History

| January 6 United States Capitol attack |

|---|

|

| Timeline • Planning |

| Background |

| Participants |

| Aftermath |

On May 19, 2021, in the aftermath of the January 6 United States Capitol attack, the House voted to form an independent bicameral commission to investigate the attack, similar to the 9/11 Commission.[27] The bipartisan Bill passed the House 252–175, with thirty-five Republicans voting in favor. The large number of defections was considered a rebuke of Minority Leader McCarthy, who reversed course and whipped against the proposal, after initially deputizing Rep. John Katko to negotiate for Republicans.[27] The proposal was defeated by a filibuster from Republicans in the Senate.[28] In late May, when it had become apparent that the filibuster would not be overcome, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi indicated that she would appoint a select committee to investigate the events as a fallback option.[29][30][31][32]

On June 30, 2021, H.Res.503, “Establishing the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol”,[33] passed the House 222–190, with all Democratic members and two Republican members, Adam Kinzinger and Liz Cheney, voting in favor.[23] Sixteen Republican members did not vote.[34] The resolution empowered Pelosi to appoint eight members to the committee, and House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy could appoint five members “in consultation” with the Speaker.[35] Pelosi indicated that she would name a Republican as one of her eight appointees.[36]

On July 1, Pelosi appointed eight members, seven Democrats and one Republican, Liz Cheney (R-WY). Bennie Thompson (D-MS) was appointed committee chairman.[37]

On July 19, McCarthy announced his five selections, recommending Jim Banks (R-IN) serve as Ranking Member, along with Jim Jordan (R-OH), Rodney Davis (R-IL), Kelly Armstrong (R-ND), and Troy Nehls (R-TX).[38] Banks, Jordan, and Nehls had voted to overturn the Electoral College results in Arizona and Pennsylvania. Banks and Jordan had also signed onto the Supreme Court case Texas v. Pennsylvania to invalidate the ballots of voters in four states.[39]

On July 21, Thompson announced that he would investigate Trump as part of the inquiry into the Capitol attack.[40] Hours later, Pelosi announced that she had informed McCarthy that she was rejecting Jordan and Banks, citing concerns for the investigation’s integrity and relevant actions and statements made by the two members. She approved the recommendations of the other three.[41] Rather than suggesting two replacements, McCarthy insisted he would not appoint anyone unless all five of his choices were approved.[42][43] When McCarthy pulled all of his picks, he eliminated all Trump defenders on the committee and cleared the field for Pelosi to control the committee’s entire makeup and workings. This was widely interpreted as a costly political miscalculation by McCarthy.[44][45][46]

On July 25, after McCarthy rescinded all of his selections, Pelosi announced that she had appointed Adam Kinzinger (R-IL), one of the ten House Republicans who voted for Trump’s second impeachment, to the committee.[47][48][49] Pelosi also hired a Republican, former Rep. Denver Riggleman (R-VA), as an outside committee staffer or advisor.[50] Cheney voiced her support and pushed for the involvement of both.[49]

On February 4, 2022, the Republican National Committee voted to censure Cheney and Kinzinger, which it had never before done to any sitting congressional Republican. The resolution formally dropped “all support of them as members of the Republican Party”, arguing that their work on the select committee was hurting Republican prospects in the midterm elections.[26][51] Kinzinger had already announced on October 29, 2021, that he would not run for reelection.[52] Cheney lost the primary for her reelection on August 16, 2022.[53]

Members

The committee’s chair was Bennie Thompson, and the vice chair was Liz Cheney. Seven Democrats and two Republicans sat on the committee.

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

In July 2021, Thompson announced the senior staff:[62]

- David Buckley as staff director. Served as CIA inspector general and House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence minority staff director.

- Kristin Amerling as deputy staff director and chief counsel. Served as deputy general counsel at the Transportation Department and chief counsel of multiple congressional committees, including Committees on Energy and Commerce and Oversight and Government Reform. She also served as Chief Investigative Counsel and Director of Oversight for the Senate’s Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee.

- Hope Goins as counsel to Chairman Thompson. Served as top advisor to Thompson on homeland security and national security matters.

- Candyce Phoenix as senior counsel and senior advisor. Serves as staff director of the House Oversight Subcommittee on Civil Rights and Civil Liberties.

- Tim Mulvey as communications director. Served as communications director for the House Committee on Foreign Affairs.

In August 2021, Thompson announced additional staff:[63][64]

- Denver Riggleman, senior technical adviser for the January 6 Committee. He previously served as a Republican U.S. Representative from Virginia and was an ex-military intelligence officer.

- Riggleman left the committee in April 2022.[65]

- Joe Maher as principal deputy general counsel from the Department of Homeland Security.

- Timothy J. Heaphy was appointed as the committee’s chief investigative counsel.[66][67]

In November 2022, Thompson disclosed the existence of a subcommittee to handle “outstanding issues” including unanswered subpoenas and whether to send transcripts of interviews to the DOJ. The subcommittee had been established about one month earlier with Raskin as chair, along with Cheney, Lofgren, and Schiff. Thompson said he selected them because “they’re all lawyers”.[68][69]

Investigation

The investigation commenced with a public hearing on July 27, 2021, at which four police officers testified. As of the end of 2021, it had interviewed more than 300 witnesses and obtained more than 35,000 documents,[70] and those totals continued to rise. By May 2022, it had interviewed over 1,000 witnesses;[71] some of those interviews were recorded.[72] By October 2022, it had obtained over 1,000,000 documents[3] and reviewed hundreds of hours of videos (such as security camera and documentary footage).[73] During the pendency of the investigation, the select committee publicly communicated some of its information.

The select committee split its multi-pronged investigation into multiple color-coded teams,[74][75][76] each focusing on a specific topic like funding, individuals’ motivations, organizational coalitions, and how Trump may have pressured other politicians.[77] These were:

- Green Team investigated the money trail and whether or not Trump and Republican allies defrauded their supporters by spreading misinformation regarding the 2020 presidential election, despite knowing the claims were not true.

- Gold Team investigated whether members of Congress participated or assisted in Trump’s attempted to overturn the election. They are also looking into Trump’s pressure campaign on local and state officials as well as on executive departments, like the Department of Justice, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, and others to try to keep himself in power.

- Purple Team investigated the involvement of domestic violent extremist groups — such as the QAnon movement, militia groups, Oath Keepers, and Proud Boys — and how they used social media including Facebook, Gab, and Discord.[78]

- Red Team investigated the planners of the January 6th rally and other “Stop the Steal” organizers and if they knew the rally would intentionally become violent.

- Blue Team researched the threats leading up to the attack, how intelligence was shared among law enforcement, and their preparations or lack thereof.[79] Additionally, Blue Team had access to thousands of documents from more than a dozen agencies that other security reviews did not have.[80]

The select committee’s investigation and its findings were multi-faceted.

A reform of election certification procedures (as governed by the Electoral Count Act of 1887) was passed in the December 2022 omnibus spending bill.[81][82] Committee members had begun collaborating on this reform in 2021.[83]

The select committee’s findings may also be used in arguments to hold individuals, notably Donald Trump,[71] legally accountable.

Simultaneous investigations by the Justice Department

The United States Department of Justice (DOJ) is probing the months-long efforts to falsely declare that the election was rigged, including pressure on the DOJ, the fake-electors scheme, and the events of January 6 itself.[84]

The judicial branch has also made related observations and rulings. In March 2022, federal judge David Carter said it was “more likely than not” that Trump has engaged in a conspiracy with John Eastman to commit federal crimes, and described their attempt as “a coup in search of a legal theory”.[85]

On November 18, 2022, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland announced the appointment of John L. “Jack” Smith as the Special Counsel to oversee the DOJ’s ongoing investigations into the FBI investigation into Donald Trump’s handling of government documents as well the January 6 investigation.[86] Garland praised Smith’s experience and said: “I am confident that this appointment will not slow the completion of these investigations.” Smith promised to investigate “independently and in the best traditions of the Department of Justice … to whatever outcome the facts and the law dictate.”[87]

While the committee’s investigation was ongoing, it shared some information with the DOJ,[88] but it waited until it had finished its work in December 2022 before turning over everything.[89] The DOJ had sent a letter on April 20, 2022, asking for transcripts of past and future interviews. Thompson, the committee chair, told reporters he did not intend to give the DOJ “full access to our product” especially when “we haven’t completed our own work”. Instead, the select committee negotiated for a partial information exchange.[16] On June 15, the DOJ repeated its request. They gave an example of a problem they had encountered: The trial of the five Proud Boys indicted for seditious conspiracy had been rescheduled for the end of 2022 because the prosecutors and the defendants’ counsel did not want to start the trial without the relevant interview transcripts.[90] On July 12, 2022, the committee announced it was negotiating with the DOJ about the procedure for information-sharing and that the committee had “started producing information” related to the DOJ’s request for transcripts.[91]

On December 19, 2022, the House select committee publicly voted to recommend that the DOJ bring criminal charges against Trump[92] (a long-anticipated move)[93] as well as against John Eastman.[92] Some critics had argued against making criminal referrals, as such a recommendation by a congressional committee has no legal force[94] and could appear to politically taint the DOJ’s investigation.[95] However, a committee spokesperson had said on December 6 that criminal referrals would be “a final part” of the committee’s investigative work.[96] Schiff acknowledged on December 11 that any referral would be “symbolic” but was nevertheless “important”[97] — he had said in September that he hoped the committee would unanimously refer Trump to the DOJ[98] — while Representative Raskin said on December 13, “Everybody has made his or her own bed in terms of their conduct or misconduct.”[99]

Information received from Mark Meadows

In September 2021, the select committee subpoenaed former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows. Meadows initially cooperated, but in December, without providing all requested documents, he sued to block the two congressional subpoenas.[100] On December 14, 2021, the full House voted to hold Meadows in contempt of Congress.[101] In a July 15, 2022 amicus brief[102] filed at the request of U.S. District Court Judge Carl J. Nichols,[103] the DOJ acknowledged that the House subpoena had been justified and that Meadows had only “qualified” immunity given that Trump was no longer in office.[104][105] On October 31, 2022, the judge ruled that the congressional subpoenas were “protected legislative acts” that were “legitimately tied to Congress’s legislative functions”.[106]

Although the congressional subpoenas were valid, DOJ decided not to criminally charge him for defying them.[107] In 2022, Meadows did comply with a DOJ subpoena in the DOJ investigation of January 6.[108] In 2023, he was indicted in Georgia for his alleged role in election interference in that state.[109]

Meadows had routinely burned documents in his office fireplace after meetings during the transition period; Cassidy Hutchinson testified to the committee that she had seen him do this a dozen times between December 2020 and mid-January 2021.[110]

In late 2021, before Meadows stopped cooperating, he provided thousands of emails and text messages[111][100] that revealed efforts to overturn the election results:

- The day after the election, former Texas governor and former Secretary of Energy Rick Perry sent Meadows a proposed strategy for Republican-controlled state legislatures to choose electors and send them directly to the Supreme Court before their states had determined voting results.[112][113]

- Fox News host Sean Hannity exchanged text messages with Meadows suggesting that Hannity was aware in advance of Trump’s plans for January 6. Hannity texted on December 31, 2020, that he was afraid that many U.S. attorneys would resign, adding: “I do NOT see Jan. 6 happening the way [Trump] is being told.” He texted in the evening of January 5: “I am very worried about the next 48 hours.” The committee wrote to Hannity asking him to voluntarily answer questions.[114][115][116]

- During the attack, Donald Trump Jr. told Meadows that his father must “lead now” by making an Oval Office address because “[i]t has gone too far. And gotten out of hand.”[117][118]

- Two Fox News allies of Trump texted that the Capitol attack was destroying the president’s legacy.[117][118]

- Representative Jim Jordan asked Meadows if Vice President Mike Pence could identify “all the electoral votes that he believes are unconstitutional”.[119]

- The day after the riot, one text stated that “We tried everything we could in our objections to the 6 states. I’m sorry nothing worked.”[120][119]

Meadows also participated in a call with a Freedom Caucus group including Rudy Giuliani, Representative Jim Jordan, and Representative Scott Perry during which they planned to encourage Trump supporters to march to the Capitol on January 6.[121]

Meadows also exchanged post-election text messages with Ginni Thomas, the wife of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, in which they expressed support of Trump’s claims of election fraud. On November 5, in the first of 29 text messages, Ginni Thomas sent to Meadows a link to a YouTube video about the election.[122] She emailed Arizona and Wisconsin lawmakers on November 9 to encourage them to choose different electors, exchanged emails with John Eastman, and attended the rally on January 6.[123][124][125]

Some of the communications revealed Trump allies who privately expressed disagreement with the events of January 6 while defending Trump in public:

- Donald Trump Jr. pleaded with Meadows during the January 6 riot to convince his father that “[i]t has gone too far and gotten out of hand”[126]

- Similarly, Fox News hosts Brian Kilmeade, Sean Hannity, and Laura Ingraham asked Meadows to persuade Trump to appear on TV and quell the riot.[127]

In mid-2022, CNN spoke to over a dozen people who had texted Meadows that day, and all of them said they believed that Trump should have tried to stop the attack.[128]

One of the most revealing documents provided by Meadows was a PowerPoint presentation[129][130] describing a strategy for overturning the election results. The presentation had been distributed by Phil Waldron, a retired Army colonel (now owning a bar in Texas)[131] who specialized in psychological operations and who later became a Trump campaign associate. A 36-page version appeared to have been created on January 5,[132][129] and Meadows received a version that day.[133][134][135] He eventually provided a 38-page version to the committee.[132] It recommended that Trump declare a national security emergency to delay the January 6 electoral certification, invalidate all ballots cast by machine, and order the military to seize and recount all paper ballots.[133][134] (Meadows claims he personally did not act on this plan.[133]) Waldron was associated with former Trump national security advisor Michael Flynn and other military-intelligence veterans who played key roles in spreading false information to allege the election had been stolen from Trump.[136][131] Politico reported in January 2022 that Bernard Kerik had testified to the committee that Waldron also originated the idea of a military seizure of voting machines, which was included in a draft executive order dated December 16.[137][138] The next month, Politico published emails between Waldron, Flynn, Kerik, Washington attorney Katherine Friess, and Texas entrepreneur Russell Ramsland that included another draft executive order dated December 16. That draft was nearly identical to the draft Politico had previously released; embedded metadata indicated it had been created by One America News anchor Christina Bobb. An attorney, Bobb had also been present at the Willard Hotel command center.[139][140]

Meadows testified that he organized a daily morning call beginning January 7, 2021, with Mike Pompeo and Mark Milley.[141]

As of August 2023, the extent of Meadows’s cooperation in various investigations remained unknown to the public.[142] Prosecutors in the Georgia indictment reportedly do not intend to offer him a plea deal.[143] He has said he wants to be tried separately from the other Georgia defendants[144] and has also sought for his case to be removed to federal court.[145]

Obstacles

Release of documents from the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA)

One of the main challenges to the committee’s investigation was Trump’s use of legal tactics to try to block the release of the White House communication records held at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).[146] He succeeded in delaying the release of the documents for about five months. The committee received the documents on January 20, 2022.[147][148]

Some of the documents had been previously torn up by Trump and taped back together by NARA staff.[149] Trump is said to have routinely shredded and flushed records by his own hand, as well as to have asked staff to place them in burn bags, throughout his presidency.[150][151] Additionally, as the presidential diarist testified to the committee in March 2022, the Oval Office did not send the diarist detailed information about Trump’s daily activities on January 5 and 6, 2021.[152]

Trump’s phone records from the day of the attack, as provided by NARA to the committee, did not log any calls during the seven-and-a-half hours that the Capitol was under siege,[152] suggesting he was using a “burner” cell phone during that time.[153] He is said to have routinely used burner phones during his presidency.[154] When the committee subpoenaed his personal communication records,[155][3] his lawyers claimed he had no such records.[156]

Trump tried to hide the fact that he had pressured the Defense Secretary and DOJ to seize voting machines immediately after the election in six states where he had lost.[157] To prevent the Committee gaining access to relevant White House records, he sought an injunction from the Supreme Court, which dismissed his request on January 19, 2022.[158]

The committee began its request for the NARA records in August 2021.[159][160] Trump asserted executive privilege over the documents.[161] Current president Joe Biden rejected that claim,[162][163] as did a federal judge (who noted that Trump was no longer president),[164] the DC Circuit Court of Appeals,[165] and the U.S. Supreme Court.[166][167] The committee agreed to a Biden administration request for NARA to withhold certain sensitive documents about unrelated national security matters but continued to litigate until it received the potentially relevant records.[168]

Republicans not testifying

From the beginning of the investigation, Trump told Republican leaders not to cooperate with the committee.[169][170][171][172] While many testified voluntarily,[173] the committee also issued subpoenas[174] to legally compel others’ testimony. Some people who were subpoenaed refused to testify: Roger Stone and John Eastman pleaded their Fifth Amendment rights, while Steve Bannon and Mark Meadows were found in contempt of Congress. In December 2021, Michael Flynn sued to block a subpoena for his phone records and to delay his testimony, though a federal judge dismissed his suit within a day.[175]

Trump White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson spoke to the committee several times in early 2022 while represented by Stefan Passantino, a Trump ally who wanted her to skirt the committee’s questions. She spoke to the committee without Passantino’s knowledge; former White House aide Alyssa Farah Griffin was her backchannel connection for the additional testimony.[176][177] Hutchinson later dismissed Passantino,[176][177] hired Jody Hunt instead, and had another closed-door deposition on June 20, 2022, a week before she appeared at a public hearing.[110]

Bill Stepien, Trump’s final campaign manager, was subpoenaed and planned to testify live for the second public hearing on June 13, 2022. However, he canceled his appearance an hour before the hearing started, as his wife went into labor. The select committee instead aired clips of Stepien’s previously recorded deposition;[178] the scramble to rearrange the presentation delayed the start of the nationally televised hearing by 45 minutes.[179][180]

On October 21, 2022, the committee subpoenaed Trump for documents and testimony. They requested all his communications on the day of the Capitol attack and many of his political communications in the preceding months.[155][181][182] On November 9, Trump’s lawyers wrote to the committee saying he possessed “no documents” relevant to the subpoena. On November 11, they sued to block the subpoena, arguing that the committee could obtain the information from sources other than Trump.[156]

Pence chose not to speak to the select committee, though the committee had long deliberated calling him.[183][184] On January 4, 2022, Chair Thompson told reporters that Pence should “do the right thing and come forward and voluntarily talk to the committee”. While acknowledging that the committee had not formally invited Pence to speak to them, Thompson suggested: “if he offered, we’d gladly accept.”[185] The committee reportedly considered Pence’s testimony particularly important,[186] though, in April, Thompson told reporters they would not bother calling him, especially having already confirmed important information through his former aides Marc Short and Greg Jacob.[187] On August 17, Pence told an audience at Saint Anselm College that he was waiting for the committee to invite him: “If there was an invitation to participate, I’d consider it.”[188] He described his experience of the attack on the Capitol in his autobiography, which was scheduled to be published a week after the November 2022 midterm elections.[189] As of late November, Pence was reportedly more interested in testifying before the DOJ.[190][191] “I think it’s sad that he didn’t want to come to us”, Representative Pete Aguilar told CNN in early December 2022.[192]

Secret Service, DHS and Pentagon text messages deleted

Soon after the attack on the Capitol, the Secret Service assigned new phones.[193] In February 2021, the office of Department of Homeland Security Inspector General Joseph Cuffari, a Trump appointee, learned that text messages of Secret Service agents had been lost. He considered sending data specialists to attempt to retrieve the messages, but a decision was made against it.[194] In June 2021, DHS asked for text messages from 24 individuals—including the heads for Trump and Pence security, Robert Engel and Tim Giebels—and did not receive them. In October 2021, DHS considered publicizing the Secret Service’s delays.[195][196] On July 26, 2022, Chairman Thompson, in his capacity as Chair of the House Homeland Security Committee, and Carolyn Maloney, Chair of the House Oversight & Reforms Committee, jointly wrote to the Council of the Inspectors General on Integrity and Efficiency about Cuffari’s failure to report the lost text messages and asked CIGIE chair Allison Lerner to replace Cuffari with a new Inspector General who could investigate the matter.[197] Additionally, renewed calls to have President Biden dismiss Cuffari have started gaining traction, with Senator Dick Durbin, who chairs the Senate Judiciary Committee requesting Attorney General Garland to investigate the missing text messages. However, as of July 2022, it is unknown if President Biden will fire Cuffari as he made a campaign promise to never fire an inspector general during his tenure as POTUS.

On August 1, 2022, House Homeland Security Chairman Bennie Thompson reiterated calls for Cuffari to step down due to a “lack of transparency” that could be “jeopardizing the integrity” of crucial investigations regarding the missing Secret Service text messages.[198] That same day, an official inside the DHS inspector general’s office told Politico that Cuffari and his staff are “uniquely unqualified to lead an Inspector General’s office, and … the crucial oversight mission of the DHS OIG has been compromised.”[199] Congress also obtained a July 2021 e-mail, from deputy inspector general Thomas Kait, who told senior DHS officials there was no longer a need for any Secret Service phone records or text messages. Efforts to collect communications related to Jan. 6 were therefore shutdown by Kait just six weeks after the internal DHS investigation began. The Guardian wrote that “taken together, the new revelations appear to show that the chief watchdog for the Secret Service and the DHS took deliberate steps to stop the retrieval of texts it knew were missing, and then sought to hide the fact that it had decided not to pursue that evidence.”[200]

On August 2, 2022, CNN reported that relevant text messages from January 6, 2021, were also deleted from the phones of Trump-appointed officials at the Pentagon, despite the fact that FOIA requests were filed days after the attack on the Capitol.[201][202] The Secret Service was later reported to have been aware of online threats against lawmakers before the attack on the Capitol, according to documents obtained by the House select committee.[203]

Trump funding legal defense of Republican witnesses

Trump’s Save America PAC has paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to lawyers representing over a dozen witnesses called by the committee. [204] On September 1, 2022, Trump said on a right-wing radio show that he had recently met supporters in his office. He said he was “financially supporting” them, adding: “It’s a disgrace what they’ve done to them.”[205]

The American Conservative Union provided legal defense funds for some people who resist the committee. The organization said it only assisted people who do not cooperate with the committee and who opposed its mission, according to chairman Matt Schlapp.[206]

Republican National Committee (RNC) claiming committee is illegitimate

Though the Republican National Committee had long insisted that the committee is invalid and should not be allowed to investigate, a federal judge found on May 1, 2022, that the committee’s power is legitimate.[207] On November 30, 2022, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy wrote a letter warning the committee that the incoming Republican-majority House of Representatives planned to investigate the committee’s work in 2023.[208]

Public findings

2021 public hearings

The House select committee began its investigation with a preliminary public hearing on July 27, 2021, called “The Law Enforcement Experience on January 6th”.[209][210] Capitol and District of Columbia police testified, describing their personal experiences on the day of the attack, and graphic video footage was shown.[211]

2022 public hearings

In 2022, the Committee held ten live televised public hearings[212] that presented evidence of Trump‘s seven-part plan to overturn the 2020 elections; this included live interviews under oath (of many Republicans and some Trump loyalists),[213][214] as well as recorded sworn deposition testimony and video footage from other sources. An Executive Summary[215] of the committee’s findings was published on December 19, 2022; a Final Report[216] was published on December 22, 2022.[217]

During the first hearing on June 9, 2022, committee chair Bennie Thompson and vice-chair Liz Cheney said that President Donald Trump tried to stay in power even though he lost the 2020 presidential election. Thompson called it a “coup”.[218] The committee shared footage of the attack, discussed the involvement of the Proud Boys, and included testimony from a documentary filmmaker and a member of the Capitol Police.

The second hearing on June 13, 2022, focused on evidence showing that Trump knew he lost and that most of his inner circle knew claims of fraud did not have merit. William Barr testified that Trump had “become detached from reality” because he continued to promote conspiracy theories and pushed the stolen election myth without “interest in what the actual facts were.”[219][220]

The third hearing on June 16, 2022, examined how Trump and others pressured Vice President Mike Pence to selectively discount electoral votes and overturn the election by unconstitutional means, using John Eastman‘s fringe legal theories as justification.[221]

The fourth hearing on June 21, 2022, included appearances by election officials from Arizona and Georgia who testified they were pressured to “find votes” for Trump and change results in their jurisdictions. The committee revealed attempts to organize fake slates of alternate electors and established that “Trump had a direct and personal role in this effort.”[222][223]

The fifth hearing on June 23, 2022, focused on Trump’s pressure campaign on the Justice Department to rubber stamp his narrative of a stolen election, the insistence on numerous debunked election fraud conspiracy theories, requests to seize voting machines, and Trump’s effort to install Jeffrey Clark as acting attorney general.[224]

The exclusive witness of the sixth hearing on June 28, 2022, was Cassidy Hutchinson, top aide to former White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows.[225] She testified that White House officials anticipated violence days in advance of January 6; that Trump knew supporters at the Ellipse rally were armed with weapons including AR-15s yet asked to relax security checks at his speech; and that Trump planned to join the crowd at the Capitol and became irate when the Secret Service refused his request. Closing the hearing, Cheney presented evidence of witness tampering.[226]

The seventh hearing on July 12, 2022, showed how Roger Stone and Michael Flynn connected Trump to domestic militias like the Oath Keepers and Proud Boys that helped coordinate the attack.[227][228][229]

The eighth hearing on July 21, 2022, presented evidence and details of Trump’s refusal to call off the attack on the Capitol, despite hours of pleas from officials and insiders. According to the New York Times, the committee delivered two significant public messages: Rep. Liz Cheney made the case that Trump could never “be trusted with any position of authority in our great nation again”, while Rep. Bennie Thompson called for legal “accountability” and “stiff consequences” to “overcome the ongoing threat to our democracy.”[230]

The ninth hearing on October 13, 2022,[231][232] presented video of Roger Stone and evidence that some Trump associates planned to claim victory in the 2020 election regardless of the official results.[233][234] The committee voted unanimously to subpoena Trump for documents and testimony,[235][236] and a subpoena was issued one week later.[237] Trump refused to comply.[238]

The tenth hearing on December 19, 2022, convened to present a final overview of their investigative work to date, and the committee recommended that former President Donald Trump, John Eastman, and others be referred for legal charges. The committee also recommended that the House Ethics Committee follow up on Rep. Kevin McCarthy (CA), Rep. Jim Jordan (OH), Scott Perry (PA), and Andy Biggs (AZ) refusing to answer subpoenas.[239] The votes were unanimous.[240] Immediately after the hearing, the committee released a 154-page executive summary of its findings.[241][242][243]

Criminal referrals

On December 19, 2022, the committee criminally referred Trump to the DOJ for four suspected crimes.

Simultaneously, the committee referred John Eastman to the DOJ for the first two of those same crimes. This move was supported by a June 7, 2022, ruling by Judge David Carter. Carter had decided that one email in John Eastman’s possession, sent before January 6, contained likely evidence of a crime and that Eastman must disclose it to the House committee under the crime-fraud exception of attorney-client privilege.[248]

- Obstruction of an Official Proceeding (18 U.S.C. § 1512(c))

- Conspiracy to Defraud the United States (18 U.S.C. § 371)

The committee suggested that the DOJ look into two additional charges for Trump: conspiracy to prevent someone from holding office or performing the duties of their office, and seditious conspiracy. It noted that convictions on both of these charges had recently been delivered in the high-profile Oath Keepers trial.

- Other Conspiracy Statutes (18 U.S.C. §§ 372 and 2384)[249]

Trump and Eastman were the only individuals the committee criminally referred to the DOJ. Although the committee said that Mark Meadows, Rudy Giuliani, Jeffrey Clark had been “actors” in the plot, it decided it lacked sufficient evidence to refer them, especially given certain individuals’ unwillingness to cooperate with the investigation. “We trust that the Department of Justice will do its job”, Raskin said.[250]

Impact on other investigations

On August 1, 2023, a federal grand jury indicted Trump on four counts, three of which resemble the charges recommended by the House select committee. (Trump was not charged with incitement of insurrection.)[251] Additionally, among the co-conspirators identified in the indictment were four who’d been previously named by the House committee: John Eastman, Rudy Giuliani, Jeffrey Clark, and Kenneth Chesebro.[252]

Under the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, anyone who has “engaged” in insurrection is ineligible to hold public office. However, the process for barring someone from office was unclear. The 14th Amendment does not say if such a person must first be criminally convicted of insurrection, nor does it specify an enforcement authority or mechanism for deeming them ineligible to hold office.[253][254] In early 2022, the eligibility of two candidates in North Carolina and Georgia was questioned, but ultimately not denied, on this basis.[255][256] Later that year, a county commissioner from New Mexico became the first elected official since the Civil War era to be removed from office for participating in an insurrection.[257] On December 15, 2022, House Democrats introduced a bill that would prevent Trump specifically from running for office again.[258][259] In 2023, lawsuits were filed in several states, and on December 19, the Colorado Supreme Court ruled that Trump should be removed from the ballot in that state, based on the 14th Amendment. However, on March 4, 2024, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that no states have the power to remove Trump from the ballot. The court decided that this power lies with Congress.[260][261][262]

The select committee’s work also aided the State of Georgia’s investigation into alleged solicitations of election fraud. On May 2, 2022, Fulton County‘s District Attorney Fani Willis opened a special grand jury to consider criminal charges,[263] and on August 14, 2023, a Georgia grand jury indicted Trump on 13 counts.[264] The identities of Trump’s 18 co-defendants[265] and 30 unindicted co-conspirators[266] significantly overlap with the people identified by the House committee. In particular, Chesebro was charged with seven felonies related to electoral vote obstruction, and he pleaded guilty to one of them: conspiracy to file false documents.[267]

On April 23, 2024, Arizona indicted eleven fake electors and seven Trump allies. The Trump allies were Christina Bobb, John Eastman, Jenna Ellis, Boris Epshteyn, Rudy Giuliani, Mark Meadows, and Mike Roman. The indictment also described five unindicted coconspirators, including Trump.[268]

Witness testimony transcripts

On December 21, 2022, the committee released the first batch of hundreds of witness testimony transcripts.[21] The transcripts detailed testimony from 34 witnesses who mostly invoked the Fifth Amendment and avoided answering questions,[269] including:

- former acting Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Division Jeffrey Clark

- Trump campaign lawyer John Eastman

- conservative attorney Jenna Ellis

- former National Security Adviser Michael Flynn

- Trump ally Roger Stone

- Oath Keepers Founder Stewart Rhodes

- Proud Boys Chairman Enrique Tarrio

- conservative radio host Alex Jones

- Arizona Republican Party Chair Kelli Ward

- white nationalist Nick Fuentes[269]

On December 22, 2022, more transcripts were released. They revealed that Cassidy Hutchinson had given additional testimony on September 14–15, 2022, in which she claimed that Trump allies, including her “Trump world” attorney Stefan Passantino, had pressured her not to talk to the committee.[270][271] (Passantino would later sue the committee for $67 million in damages to his reputation. He was represented by Jesse Binall.)[272]

On December 23, 46 more interview transcripts were released, including:

- Trump’s daughter Ivanka

- former Attorney General Bill Barr

- former White House counsel Pat Cipollone

- former acting Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen

- former White House communications director Hope Hicks

- former press secretary Kayleigh McEnany

- Trump-backed attorney Sidney Powell

- Marc Short, chief of staff to Vice President Mike Pence[273]

On December 30, 2022, the committee released a third batch of witness testimony transcripts. It acted swiftly, anticipating that it would not be able to continue its work under the new Congress.[274]

Final report

On December 22, 2022, the final report was published online.[275] The report was final because the committee itself expired two weeks later when the 117th Congress ended.[276][65]

Several publishing houses printed it. An edition by Penguin Random House had a foreword by Schiff,[277] one by Celadon Books had a preface by David Remnick and an epilogue by Raskin,[278] and one by HarperCollins had an introduction by Ari Melber.[279]

Before publication

In October 2022, Representative Lofgren said the committee would likely provide an unredacted version of its final report to the DOJ at the same time the public received a redacted version.[280] In December, Representative Schiff said the committee would publish its evidence so the newly elected Republican-majority House of Representatives (soon to be sworn in for the 118th Congress) could not “cherry-pick certain evidence and mislead the country with some false narrative.”[281]

As the committee wrapped up its work in late 2022, the writers of the final report were directed to focus more on Trump’s alleged crimes (as researched by the “Gold Team” and revealed in the public hearings) and less on law enforcement’s failure to address radicalization, armed groups, and violent threats.[282] Some committee staff expressed concerns that Vice Chair Liz Cheney wanted an anti-Trump report to bolster her own political future. Another person quoted by The Washington Post anonymously rebutted that notion, saying that Cheney intended to produce a compelling narrative and thereby avoid “a worse version of the Mueller report, which nobody read”.[283] On November 27, 2022, Representative Schiff said the committee members hadn’t yet reached consensus on the report’s focus but also were “close to the putting down the pen”.[284]

The report was expected to discuss others’ responsibility for events between the election on November 3, 2020, and the electoral vote count on January 6, 2021. Topics were expected to include RNC fundraising, what the Secret Service knew, and how the National Guard responded.[192]

Though the committee held public hearings before the November 2022 midterm elections, it did not release any written report by that time.[285][286]

According to the committee’s original authorization, it was supposed to terminate 30 days after filing its final report.[33] The 118th Congress convened two weeks after the committee published the report, rendering the 30-day timeframe irrelevant.

Summary

On December 19, 2022, the same day it made the criminal referrals, the committee published an “Executive Summary” as an introduction to its final report. It outlined 17 findings central to its reasoning for criminal referrals.[287] Paraphrased, they are:[288]

- Trump lied about election fraud for the purpose of staying in power and asking for money.

- Ignoring the rulings of over 60 federal and state courts, he plotted to overturn the election.

- He pressured Pence to illegally refuse to certify the election.

- He tried to corrupt and weaponize the Justice Department to keep himself in power.

- He pressured state legislators and officials to give different election results.

- He perpetrated the fake electors scheme.

- He pressured members of Congress to object to real electors.

- He approved federal court filings with fake information about voter fraud.

- He summoned the mob and told them to march on the Capitol, knowing some were armed.

- He tweeted negatively about Pence at 2:24 p.m. on January 6, 2021, inciting more violence.

- He spent the afternoon watching television, despite his advisers’ pleas for him to stop the violence.

- This was all part of a conspiracy to overturn the election.

- Intelligence and law enforcement warned the Secret Service about Proud Boys and Oath Keepers.

- The violence wasn’t caused by left-wing groups.

- Intelligence didn’t know that Trump himself had plotted with John Eastman and Rudy Giuliani.

- In advance of January 6, the Capitol Police didn’t act on their police chief’s suggestion to request backup from the National Guard.

- On January 6, the Defense Secretary, not Trump, called the National Guard.

Full report

The report placed blame on “one man”, former U.S. President Donald Trump, for inciting the riot.[275] It provided detail about a robust, organized campaign to assemble and deliver a bogus slate of electors and named lesser known Trump lawyer Kenneth Chesebro as the plot’s architect.[289][290] According to the final report, Donald Trump “sought to corrupt the US Department of Justice” by pleading with department officials to make false statements regarding the presidential elections, had failed to deploy the DC National Guard during the attack despite having the authority to do so, and made “multiple efforts” to contact witnesses summoned to testify before the House Select Committee.[291][292] The report accused Donald Trump of engaging in a criminal “multi-part conspiracy” to overturn the results of the 2020 election.”[293]

In the two months between the election and the Capitol attack, Trump allies engaged in “at least 200 apparent acts of public or private outreach, pressure, or condemnation” of state election officials. They had 68 communications with those officials (including meetings, phone calls, and texts), and they made 125 social media posts about those officials.[294]

Timeline of proceedings

2021

July 2021

- July 27: The committee held its first public hearing, featuring testimony from four police officers who were in the front line as rioters attacked the Capitol.[295][296]

- Daniel Hodges, a Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia officer, said he was crushed in a doorway between rioters and a police line.[c][297][298][299]

- Michael Fanone, a Metropolitan Police Department officer, said rioters pulled him into the crowd, beat him with a flagpole, stole his badge, repeatedly tased him with his taser and went for his gun.[297][300][301] He criticized those who downplayed the attack.[297][299]

- Harry Dunn, a private first class of the U.S. Capitol Police, spoke about the racial abuse he and other officers experienced during the attack.[297][299]

- Aquilino Gonell, a U.S. Capitol Police sergeant, said he was beaten with a flagpole and chemically sprayed.[297][299]

August 2021

- August 23: Committee investigators reportedly planned to seek phone records of multiple people, including members of Congress.[302]

- August 25: The committee sought records of at least 30 members of Trump’s inner circle from seven government agencies and the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), which preserves White House communication records. The committee’s letter explained it was repeating requests that “multiple committees of the House of Representatives” had made on March 25, 2021.[159][160] (Several weeks later, it was revealed that they specifically sought records from White House Chief of Staff Mark Meadows and some Republican members of Congress.)[303]

- August 27: The committee demanded records from 15 social media companies going back to the spring of 2020.[304]

September 2021

The committee sought to identify whether the White House was involved in planning the Capitol attack and whether Trump personally had advance knowledge of it.[305] The committee considered issuing subpoenas for call records or testimony of senior Trump administration officials including Meadows, Deputy Chief of Staff Dan Scavino and former Trump campaign manager Brad Parscale.[306]

- September 23: The committee issued subpoenas to Meadows, Scavino, chief strategist Steve Bannon, and Pentagon official and former Devin Nunes aide Kash Patel.[307] Documents were demanded by October 7.[308] Bannon and Patel were instructed to testify on October 14, and Meadows and Scavino on October 15.[309][310] Trump and his attorneys instructed the four aides (as was reported two weeks later) to defy the orders and provide neither documents nor testimony.[169][170][171]

- September 29: Amy Kremer and ten others affiliated with her organization Women for America First, which held the permit for the Stop the Steal rally that preceded the Capitol attack, were subpoenaed by the committee.[311] Among these eleven people was Katrina Pierson, national spokesperson for Trump’s 2016 campaign.

October 2021

- October 7: As the committee issued further subpoenas to Stop the Steal LLC, Stop the Steal campaign organizer Ali Alexander, and fellow rally organizer Nathan Martin,[312][313] Trump announced he would assert executive privilege to withhold the documents the committee had requested in August.[161]

- October 8:

- White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki says Biden would not honor Trump’s request to assert executive privilege to stop NARA from providing these documents.[162][161][314] Nevertheless, Trump writes NARA asserting privilege over about forty documents.[162] The same day, White House counsel Dana Remus advises NARA archivist David Ferriero that the challenged documents were to be released following a 30-day courtesy warning to Trump.[315][316]

- A lawyer for Bannon says in a letter to the committee that Bannon would not comply with the subpoena for his testimony, because Trump had asserted executive privilege and instructed him to defy the subpoena.[172]

- October 13: The committee subpoenas Jeffrey Clark and schedules him to provide documents and testimony later in the month. As assistant attorney general, Clark angled for a promotion to attorney general by promising Trump he would help overturn the election results. Former acting attorney general Jeffrey Rosen, who resisted Clark’s efforts to interfere with the election outcome, is interviewed by the committee.[317][318]

- October 14: After Bannon does not appear for his scheduled deposition, the committee says it would initiate proceedings to hold Bannon in criminal contempt.[319] The committee also announces that Patel and Meadows were “engaging” with their investigation, and postpones both their depositions scheduled for October 14 and 15 respectively.[320] Scavino, meanwhile, also has his October 15 deposition postponed because the committee was unable to locate him,[321] and he did not formally receive the subpoena until October 8.[322][323][320]

- October 18: Trump sues to prevent NARA from turning over the records to the committee or at least to allow him “to conduct a full privilege review of all of the requested materials” so he can choose which records NARA provides. His lawsuit, submitted by attorney Jesse R. Binnall, complains that the records request is “illegal, unfounded, and overbroad” and amounts to a “fishing expedition”.[324][325] Meanwhile, NARA plans to release the documents on November 12.[326]

- October 19: The committee votes unanimously to adopt a contempt of Congress report against Bannon and refer it to the full House for a vote.[327]

- October 21: All 220 House Democrats and 9 House Republicans vote to hold Bannon in contempt of Congress, referring his case to the DOJ, which will decide whether to prosecute him.[328][329]

- October 22: CNN reports that Cheney and Kinzinger have interviewed former Trump director of strategic communications Alyssa Farah. She had resigned in December 2020 and told CNN after the January 6 attack that Trump had lied to the American people about the election results.[330]

- October 25: Biden once again says he would not assert executive privilege; this regarded a second batch of documents the committee had requested from NARA.[163]

- October 26: The Washington Post reports that more people are expected to be subpoenaed, including legal scholar John Eastman, who supported Trump’s claims about the 2020 election.[331][332]

- October 29: Jeffrey Clark, having parted ways with his attorney several days previously, does not appear for his scheduled deposition.[333]

- October 30: In a court filing, NARA details that Trump sought to block about 750 pages of documents among the nearly 1,600 requested by the committee, including hundreds of pages of statements and talking points by Trump press secretary Kayleigh McEnany; daily presidential diaries, schedules, and appointment information; White House visitor, activity, and phone logs from on and around January 6; drafts of speeches, remarks, and correspondence relating to the Capitol attack; and handwritten notes from chief of staff Mark Meadows.[334]

November 2021

- November 5: Jeffrey Clark and his new attorney meet with investigators to state Clark would not cooperate unless compelled by a court order, asserting that Trump’s “confidences are not his to waive”, citing attorney-client privilege. In a letter to the committee, Clark’s attorney cites a letter from a Trump attorney specifically stating Trump would not try to block Clark’s testimony.[333][335][336]