Summary

Most of the top executives in the Biden administration are in his Cabinet. Other executives report to the Secretary of their cabinet’s agency. For example, the Surgeon General reports to the Secretary of Health and Human Services. The Cabinet’s role is to advise the President on any subject he or she may require relating to the duties of each member’s respective office.

The cabinet members are displayed in this slider in order of succession to the Presidency. Additional important executives are listed afterwards.

OnAir Post: Top executives in Biden administration

About

Source: Wikipedia

The Cabinet of the United States is a body consisting of the vice president of the United States and the heads of the executive branch’s departments in the federal government of the United States, which is regarded as the principal advisory body to the president of the United States. The president is not formally a member of the Cabinet.

The heads of departments, appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, are members of the Cabinet, and acting department heads also sit at the Cabinet meetings whether or not they have been officially nominated for Senate confirmation. The president may designate heads of other agencies and non-Senate-confirmed members of the Executive Office of the President as members of the Cabinet.

Web Links

Wikipedia

Contents

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the United States |

|---|

|

The Cabinet of the United States is the principal official advisory body to the president of the United States. The Cabinet meets with the president in a room adjacent to the Oval Office. The president chairs the meetings but is not formally a member of the Cabinet. The heads of departments, appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate, are members of the Cabinet, and acting department heads also participate in Cabinet meetings whether or not they have been officially nominated for Senate confirmation. The president may designate heads of other agencies and non-Senate-confirmed members of the Executive Office of the President as members of the Cabinet.

The Cabinet does not have any collective executive powers or functions of its own, and no votes need to be taken. There are 26 members: the vice president, 15 department heads, and 10 Cabinet-level officials, all except two of whom require Senate confirmation. During Cabinet meetings, the members sit in the order in which their respective department was created, with the earliest being closest to the president and the newest farthest away.[1]

The members of the Cabinet serve at the pleasure of the president, who can dismiss them at any time without the approval of the Senate, as affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States in Myers v. United States (1926) or downgrade their Cabinet membership status. Often it is legally possible for a Cabinet member to exercise certain powers over his or her own department against the president’s wishes, but in practice this is highly unusual due to the threat of dismissal. The president also has the authority to organize the Cabinet, such as instituting committees. Like all federal public officials, Cabinet members are also subject to impeachment by the House of Representatives and trial in the Senate for “treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors”.

The Constitution of the United States does not explicitly establish a Cabinet. The Cabinet’s role, inferred from the language of the Opinion Clause (Article II, Section 2, Clause 1) of the Constitution is to provide advice to the president. Additionally, the Twenty-fifth Amendment authorizes the vice president, together with a majority of the heads of the executive departments, to declare the president “unable to discharge the powers and duties of his office”. The heads of the executive departments are—if eligible—in the presidential line of succession.

History

The tradition of the Cabinet arose out of the debates at the 1787 Constitutional Convention regarding whether the president would exercise executive authority solely or collaboratively with a cabinet of ministers or a privy council. As a result of the debates, the Constitution (Article II, Section 1, Clause 1) vests “all executive power” in the president singly, and authorizes—but does not compel—the president (Article II, Section 2, Clause 1) to “require the Opinion, in writing, of the principal Officer in each of the executive Departments, upon any Subject relating to the Duties of their respective Offices”.[2][3] The Constitution does not specify what the executive departments will be, how many there will be, or what their duties will be.

George Washington, the first president of the United States, organized his principal officers into a Cabinet, and it has been part of the executive branch structure ever since. Washington’s Cabinet consisted of five members: himself, Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of War Henry Knox and Attorney General Edmund Randolph. Vice President John Adams was not included in Washington’s Cabinet because the position was initially regarded as a legislative officer (president of the Senate).[4] Furthermore, until there was a vacancy in the presidency (which did not occur until the death of William Henry Harrison in 1841) it was not certain that a vice president would be allowed to serve as president for the duration of the original term as opposed to merely acting as president until new elections could be held. It was not until the 20th century that vice presidents were regularly included as members of the Cabinet and came to be regarded primarily as a member of the executive branch.

Presidents have used Cabinet meetings of selected principal officers but to widely differing extents and for different purposes. During President Abraham Lincoln‘s administration, Secretary of State William H. Seward advocated the use of a parliamentary-style Cabinet government. However, Lincoln rebuffed Seward. While a professor Woodrow Wilson also advocated a parliamentary-style Cabinet, but after becoming president did not implement it in his administration. In recent administrations, Cabinets have grown to include key White House staff in addition to department and various agency heads. President Ronald Reagan formed seven sub-cabinet councils to review many policy issues, and subsequent presidents have followed that practice.[3]

Federal law

In 3 U.S.C. § 302 with regard to delegation of authority by the president, it is provided that “nothing herein shall be deemed to require express authorization in any case in which such an official would be presumed in law to have acted by authority or direction of the president.” This pertains directly to the heads of the executive departments as each of their offices is created and specified by statutory law (hence the presumption) and thus gives them the authority to act for the president within their areas of responsibility without any specific delegation.

Under 5 U.S.C. § 3110 (also known as the 1967 Federal Anti-Nepotism statute), federal officials are prohibited from appointing their immediate family members to certain governmental positions, including those in the Cabinet.[5]

Under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act of 1998, an administration may appoint acting heads of department from employees of the relevant department. These may be existing high-level career employees, from political appointees of the outgoing administration (for new administrations), or sometimes lower-level appointees of the administration.[6]

Confirmation process

The heads of the executive departments and all other federal agency heads are nominated by the president and then presented to the Senate for confirmation or rejection by a simple majority (although before the use of the “nuclear option” during the 113th United States Congress, they could have been blocked by filibuster, requiring cloture to be invoked by 3⁄5 supermajority to further consideration). If approved, they receive their commission scroll, are sworn in, and begin their duties. When the Senate is not in session, the president can appoint acting heads of the executive departments, and do so at the beginning of their term.

An elected vice president does not require Senate confirmation, nor does the White House Chief of Staff, which is an appointed staff position of the Executive Office of the President.

Salary

The heads of the executive departments and most other senior federal officers at cabinet or sub-cabinet level receive their salary under a fixed five-level pay plan known as the Executive Schedule, which is codified in Title 5 of the United States Code. Twenty-one positions, including the heads of the executive departments and others, receiving Level I pay are listed in 5 U.S.C. § 5312, and those forty-six positions on Level II pay (including the number two positions of the executive departments) are listed in 5 U.S.C. § 5313. As of January 2023, the Level I annual pay was set at $235,600.

The annual salary of the vice president is $235,300.[7] The salary level was set by the Government Salary Reform Act of 1989, which provides an automatic cost of living adjustment for federal employees. The vice president receives the same pension as other members of Congress as the president of the Senate.[8]

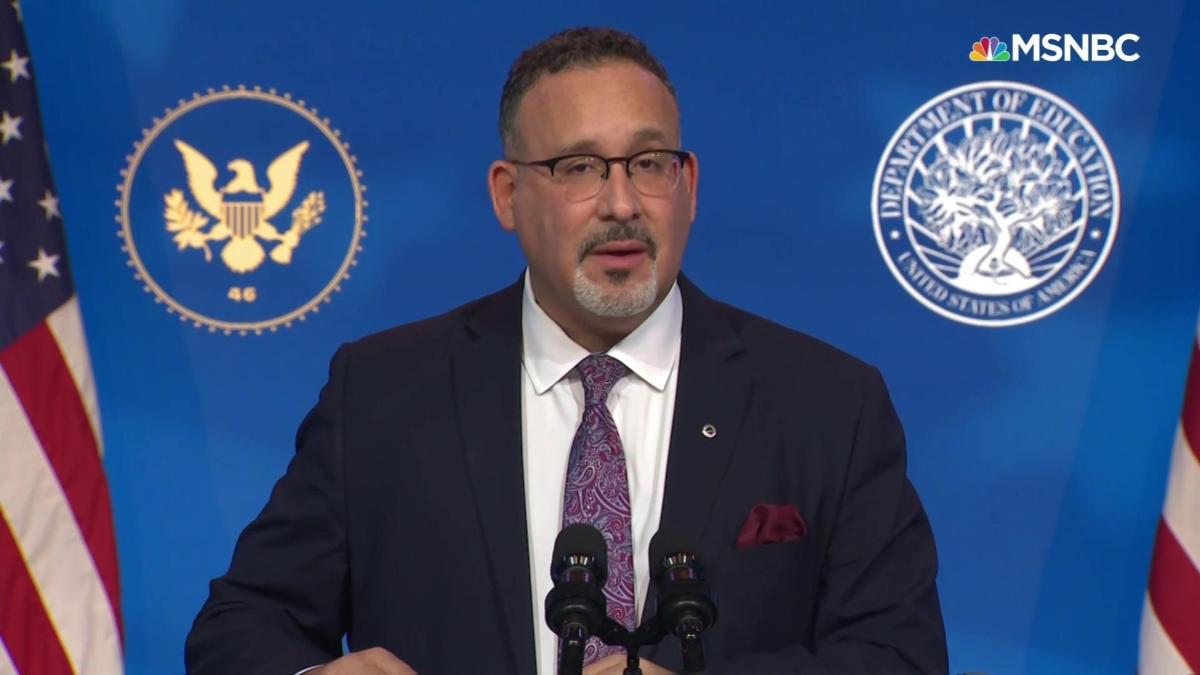

Current Cabinet and Cabinet-rank officials

The individuals listed below were nominated by President Joe Biden to form his Cabinet and were confirmed by the United States Senate on the date noted or are serving as acting department heads by his request, pending the confirmation of his nominees.

Vice president and the heads of the executive departments

The Cabinet permanently includes the vice president and the heads of 15 executive departments, listed here according to their order of succession to the presidency. The speaker of the House and the president pro tempore of the Senate follow the vice president and precede the secretary of state in the order of succession, but both are in the legislative branch and are not part of the Cabinet.

Cabinet-level officials

The president may designate additional positions to be members of the Cabinet, which can vary under each president. They are not in the line of succession and are not necessarily officers of the United States.[9]

Former executive and Cabinet-level departments

- Department of War (1789–1947), headed by the secretary of war: renamed Department of the Army by the National Security Act of 1947.

- Department of the Navy (1798–1949), headed by the secretary of the Navy: became a military department within the Department of Defense.

- Post Office Department (1829–1971), headed by the postmaster general: reorganized as the United States Postal Service, an independent agency.

- National Military Establishment (1947–1949), headed by the secretary of Defense: created by the National Security Act of 1947 and recreated as the Department of Defense in 1949.

- Department of the Army (1947–1949), headed by the secretary of the Army: became a military department within the Department of Defense.

- Department of the Air Force (1947–1949), headed by the secretary of the Air Force: became a military department within the Department of Defense.

Renamed heads of the executive departments

- Secretary of Foreign Affairs: created in July 1781 and renamed Secretary of State in September 1789.[10]

- Secretary of War: created in 1789 and was renamed as Secretary of the Army by the National Security Act of 1947. The 1949 Amendments to the National Security Act of 1947 made the secretary of the Army a subordinate to the secretary of defense.

- Secretary of Commerce and Labor: created in 1903 and renamed Secretary of Commerce in 1913 when its labor functions were transferred to the new secretary of labor.

- Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare: created in 1953 and renamed Secretary of Health and Human Services in 1979 when its education functions were transferred to the new secretary of education.

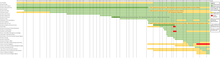

Positions intermittently elevated to Cabinet-rank

- Ambassador to the United Nations (1953–1989, 1993–2001, 2009–2018, 2021–present)

- Director of the Office of Management and Budget (1953–1961, 1969–present)

- White House Chief of Staff (1953–1961, 1974–1977, 1993–present)

- Counselor to the President (1969–1977, 1981–1985, 1992–1993): A title used by high-ranking political advisers to the president of the United States and senior members of the Executive Office of the President since the Nixon administration.[11] Incumbents with Cabinet rank included Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Donald Rumsfeld, and Anne Armstrong.

- White House Counsel (1974–1977)

- United States Trade Representative (1975–present)

- Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers (1977–1981, 1993–2001, 2009–2017, 2021–present)

- National Security Advisor (1977–1981)

- Director of Central Intelligence (1981–1989, 1995–2001)[12][13][14]

- Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency (1993–present)

- Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy (1993–2009)[15][16]

- Administrator of the Small Business Administration (1994–2001, 2012–present)

- Director of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (1996–2001): Created as an independent agency in 1979, raised to Cabinet rank in 1996,[17] and dropped from Cabinet rank in 2001.[18]

- Director of National Intelligence (2017–present)

- Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (2017–2021, 2023–present)

- Director of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (2021–present)

Proposed Cabinet departments

- Department of Industry and Commerce, proposed by Secretary of the Treasury William Windom in a speech given at a Chamber of Commerce dinner in May 1881.[19]

- Department of Natural Resources, proposed by the Eisenhower administration,[20] President Richard Nixon,[21] the 1976 GOP national platform,[22] and by Bill Daley (as a consolidation of the Departments of the Interior and Energy, and the Environmental Protection Agency).[23]

- Department of Peace, proposed by Founding Father Benjamin Rush in 1793, Senator Matthew Neely in the 1930s, Congressman Dennis Kucinich, 2020 and 2024 presidential candidate Marianne Williamson, and other members of the U.S. Congress.[24][25][26]

- Department of Social Welfare, proposed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1937.[27]

- Department of Public Works, proposed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in January 1937.[27]

- Department of Conservation (renamed Department of the Interior), proposed by President Franklin Roosevelt in January 1937.[27]

- Department of Urban Affairs and Housing, proposed by President John F. Kennedy.[28]

- Department of Business and Labor, proposed by President Lyndon B. Johnson.[29]

- Department of Community Development, proposed by President Richard Nixon; to be chiefly concerned with rural infrastructure development.[21][30]

- Department of Human Resources, proposed by President Richard Nixon; essentially a revised Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.[21]

- Department of Economic Affairs, proposed by President Richard Nixon; essentially a consolidation of the Departments of Commerce, Labor, and Agriculture.[31]

- Department of Environmental Protection, proposed by Senator Arlen Specter and others.[32]

- Department of Intelligence, proposed by former Director of National Intelligence Mike McConnell.[33]

- Department of Global Development, proposed by the Center for Global Development.[34]

- Department of Art, proposed by Quincy Jones.[35]

- Department of Business, proposed by President Barack Obama as a consolidation of the U.S. Department of Commerce’s core business and trade functions, the Small Business Administration, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the Export-Import Bank, the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency.[36][37]

- Department of Education and the Workforce, proposed by President Donald Trump as a consolidation of the Departments of Education and Labor.[38]

- Department of Health and Public Welfare, proposed by President Donald Trump as a renamed Department of Health and Human Services.[39]

- Department of Economic Development, proposed by Senator Elizabeth Warren to replace the Commerce Department, subsume other agencies like the Small Business Administration and the Patent and Trademark Office, and include research and development programs, worker training programs, and export and trade authorities like the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative with the single goal of creating and protecting American jobs.[40]

- Department of Technology, proposed by businessman and 2020 Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang.[41]

- Department of Culture, patterned on similar departments in many foreign nations, proposed by, among others, Murray Moss[42] and Jeva Lange.[43]

- When he was SEC Chairman, Harvey Pitt proposed that the Securities and Exchange Commission be elevated to Cabinet level. In July 2002, The New York Times wrote: “Democratic and Republican members of Congress joined administration officials today in ridiculing Harvey L. Pitt’s request that his pay be increased and his job as chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission be elevated to Cabinet rank … evoking an outpouring of bipartisan scorn.”[44] Pitt had tried to insert a provision into corporate antifraud legislation that would increase his pay by 21%, and also elevate his status to that of Cabinet level, at a time when the stock markets had sunk to five-year lows and some congressional leaders were calling for him to resign.[45][46][47][48]

See also

- Black Cabinet

- Brain trust

- Cabinet of Joe Biden

- Cabinet of the Confederate States of America

- Kitchen Cabinet

- List of African-American United States Cabinet members

- List of Hispanic and Latino American United States Cabinet members

- List of female United States Cabinet members

- List of foreign-born United States Cabinet members

- List of people who have held multiple United States Cabinet-level positions

- List of United States Cabinet members who have served more than eight years

- List of United States political appointments that crossed party lines

- St. Wapniacl (historical mnemonic acronym)

- United States presidential line of succession

- Unsuccessful nominations to the Cabinet of the United States

References

- ^ “Cabinet Room—White House Museum”. www.whitehousemuseum.org. Retrieved March 17, 2021.

- ^ Prakash, Sai. “Essays on Article II:Executive Vesting Clause”. The Heritage Guide to The Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ a b Gaziano, Todd. “Essays on Article II: Opinion Clause”. The Heritage Guide to The Constitution. The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved July 3, 2018.

- ^ “John Adams · George Washington’s Mount Vernon”. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2018.

- ^ Wulwick, Richard P.; Macchiarola, Frank J. (1995). “Congressional Interference With The President’s Power To Appoint” (PDF). Stetson Law Review. XXIV: 625–652. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Pierce, Olga (January 22, 2009). “Who Runs Departments Before Heads Are Confirmed?”. ProPublica. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 20, 2017.

- ^ Obama, Barack (December 19, 2014). “Adjustments of Certain Rates of Pay” (PDF). Executive Order 13686. The White House. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Purcell, Patrick J. (January 21, 2005). “Retirement Benefits for Members of Congress” (PDF). CRS Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ The White House. “The Cabinet”. Retrieved February 6, 2021.

- ^ The office of Secretary of Foreign Affairs existed under the Articles of Confederation from October 20, 1781, to March 3, 1789, the day before the Constitution came into force.

- ^ “Clayton Yeutter’s Obituary”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 31, 2018.

- ^ Tenet, George (2007). At the Center of the Storm. London: HarperCollins. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-06-114778-4.

Under President Clinton, I was a Cabinet member—a legacy of John Deutch’s requirement when he took the job as DCI—but my contacts with the president, while always interesting, were sporadic. I could see him as often as I wanted but was not on a regular schedule. Under President Bush, the DCI lost its Cabinet-level status.

- ^ Schoenfeld, Gabriel (July–August 2007). “The CIA Follies (Cont’d.)”. Commentary. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

Though he was to lose the Cabinet rank he had enjoyed under Clinton, he came to enjoy “extraordinary access” to the new President, who made it plain that he wanted to be briefed every day.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Sciolino, Elaine (September 29, 1996). “C.I.A. Chief Charts His Own Course”. New York Times. Archived from the original on May 30, 2013. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

It is no secret that Mr. Deutch initially turned down the intelligence position, and was rewarded for taking it by getting Cabinet rank.

- ^ Clinton, Bill (July 1, 1993). “Remarks by the President and Lee Brown, Director of Office of National Drug Control Policy”. White House. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

We are here today to install a uniquely qualified person to lead our nation’s effort in the fight against illegal drugs and what they do to our children, to our streets, and to our communities. And to do it for the first time from a position sitting in the President’s Cabinet.

- ^ Cook, Dave (March 11, 2009). “New drug czar gets lower rank, promise of higher visibility”. Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on March 15, 2009. Retrieved March 16, 2009.

For one thing, in the Obama administration the Drug Czar will not have Cabinet status, as the job did during George W. Bush’s administration.

- ^ “President Clinton Raises FEMA Director to Cabinet Status” (Press release). Federal Emergency Management Agency. February 26, 1996. Archived from the original on January 16, 1997. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ^ Fowler, Daniel (November 19, 2008). “Emergency Managers Make It Official: They Want FEMA Out of DHS”. CQ Politics. Archived from the original on November 29, 2008. Retrieved March 3, 2010.

During the Clinton administration, FEMA Administrator James Lee Witt met with the Cabinet. His successor in the Bush administration, Joe M. Allbaugh, did not.

(Archived March 3, 2010, by WebCite at - ^ “A Department of Commerce”. The New York Times. May 13, 1881.

- ^ Improving Management and Organization in Federal Natural Resources and Environmental Functions: Hearing Before the Committee on Governmental Affairs, U. S. Senate. Diane Publishing. April 1, 1998. ISBN 9780788148743. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved February 20, 2017 – via Google Books.

Chairman Stevens. Thank you very much. I think both of you are really pointing in the same direction as this Committee. I do hope we can keep it on a bipartisan basis. Mr. Dean, when I was at the Interior Department, I drafted Eisenhower’s Department of Natural Resources proposal, and we have had a series of them that have been presented.

- ^ a b c “116—Special Message to the Congress on Executive Branch Reorganization”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

The administration is today transmitting to the Congress four bills which, if enacted, would replace seven of the present executive departments and several other agencies with four new departments: the Department of Natural Resources, the Department of Community Development, the Department of Human Resources and the Department of Economic Affairs.

- ^ “Republican Party Platform of 1976”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. August 18, 1976. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Thrush, Glenn (November 8, 2013). “Locked in the Cabinet”. Politico. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ^ Rush, Benjamin, M.D. (1806). “A plan of a Peace-Office for the United States”. Essays, Literary, Moral and Philosophical (2nd ed.). Thomas and William Bradford, Philadelphia. pp. 183–188. Retrieved June 3, 2010.

benjamin rush peace plan office.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schuman, Frederick L. (1969). Why a Department of Peace. Beverly Hills: Another Mother for Peace. p. 56. OCLC 339785.

- ^ “History of Legislation to Create a Dept. of Peace”. Archived from the original on July 20, 2006.

- ^ a b c “10—Summary of the Report of the Committee on Administrative Management”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 13, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

Overhaul the more than 100 separate departments, boards, commissions, administrations, authorities, corporations, committees, agencies and activities which are now parts of the Executive Branch, and theoretically under the President, and consolidate them within twelve regular departments, which would include the existing ten departments and two new departments, a Department of Social Welfare, and a Department of Public Works. Change the name of the Department of Interior to Department of Conservation.

- ^ “23—Special Message to the Congress Transmitting Reorganization Plan 1 of 1962”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ “121–Special Message to the Congress: The Quality of American Government”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

In my State of the Union Address, and later in my Budget and Economic Messages to the Congress, I proposed the creation of a new Department of Business and Labor.

- ^ “33—Special Message to the Congress on Rural Development”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ “116—Special Message to the Congress on Executive Branch Reorganization”. The University of California, Santa Barbara—The American Presidency Project. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

The new Department of Economic Affairs would include many of the offices that are now within the Departments of Commerce, Labor and Agriculture. A large part of the Department of Transportation would also be relocated here, including the United States Coast Guard, the Federal Railroad Administration, the St. Lawrence Seaway Development Corporation, the National Transportation Safety Board, the Transportation Systems Center, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Motor Carrier Safety Bureau and most of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. The Small Business Administration, the Science Information Exchange program from the Smithsonian Institution, the National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety from the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and the Office of Technology Utilization from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration would also be included in the new Department.

- ^ “Public Notes on 02-RMSP3”. Archived from the original on June 13, 2017. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- ^ “A Conversation with Michael McConnell”. Council on Foreign Relations (Federal News Service, rush transcript). June 29, 2007. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved January 9, 2013.

- ^ “Time for a Cabinet-Level U.S. Department of Global Development”. The Center for Global Development. Archived from the original on January 14, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2017.

- ^ Clarke, John Jr. (January 16, 2009). “Quincy Jones Lobbies Obama for Secretary of Culture Post”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 8, 2012. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ “President Obama Announces proposal to reform, reorganize and consolidate Government”. whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 8, 2017 – via National Archives.

- ^ “Obama Suggests ‘Secretary of Business’ in a 2nd Term—Washington Wire—WSJ”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 1, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ “White House Proposes Merging Education And Labor Departments”. NPR.org. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ “Delivering Government Solutions in the 21st Century | Reform Plan and Reorganization Recommendations” (PDF). whitehouse.gov. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 12, 2019.

- ^ Warren, Team (June 4, 2019). “A Plan For Economic Patriotism”. Medium. Archived from the original on July 31, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2019.

- ^ “Regulate AI and other Emerging Technologies”. Andrew Yang for President. Archived from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved August 21, 2019.

- ^ Garber, Megan (July 1, 2013). “Should the U.S. Have a Secretary of Culture?”. The Atlantic. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ “Hey Joe—appoint a culture secretary”. theweek.com. November 16, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Stephen Labaton (July 25, 2002). “S.E.C. Chief Draws Ridicule In Quest for Higher Status,” The New York Times.

- ^ Labaton, Stephen (October 9, 2002). “Top Democrats and White House Battle Over S.E.C. Chairman”. The New York Times.

- ^ Stephen Labaton (November 6, 2002). “S.E.C.’s Embattled Chief Resigns In Wake of Latest Political Storm,” The New York Times.

- ^ “SEC Chairman Harvey Pitt shows a tin ear,” Houston Chronicle, July 25, 2002.

- ^ “Lawmakers blast Pitt’s pay request”. Chron. July 25, 2002.

Further reading

- Bennett, Anthony. The American President’s Cabinet. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Macmillan, 1996.ISBN 0-333-60691-4. A study of the U.S. Cabinet from Kennedy to Clinton.

- Grossman, Mark. Encyclopedia of the United States Cabinet (Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO; three volumes, 2000; reprint, New York: Greyhouse Publishing; two volumes, 2010). A history of the United States and Confederate States Cabinets, their secretaries, and their departments.

- Rudalevige, Andrew. “The President and the Cabinet”, in Michael Nelson, ed., The Presidency and the Political System, 8th ed. (Washington, D.C.: CQ Press, 2006).

External links

- Official site of the President’s Cabinet

- U.S. Senate’s list of Cabinet members who did not attend the State of the Union Address (since 1984)