Summary

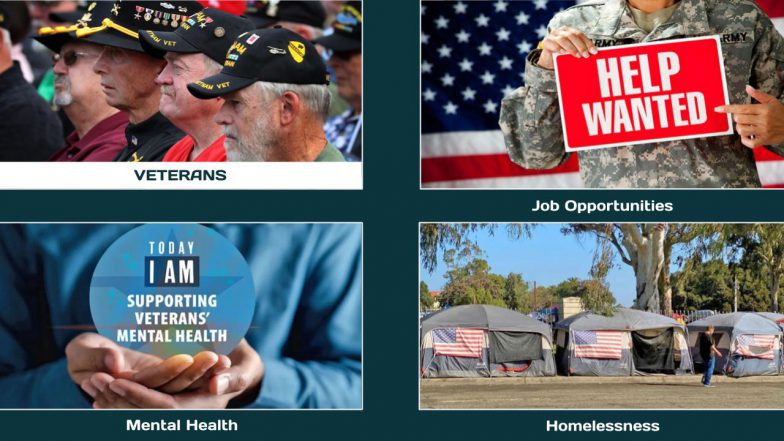

There are many issues related to Veterans that Congress is looking to address with legislation.

We have identified three issues for particular focus: Mental Health, Job Opportunities, Homelessness. This post summarizes the key challenges and solutions around Veterans and the ways Congress and the government are addressing them. Go to the posts on each issue to learn more about each issue and how Congress is addressing the problems.

In the Discussion section of this post, you can ask our curators questions, make suggestions, and discuss other issues related to Veterans not being addressed in the three focused issues.

ConEquip Parts and Equipment – 11/11/2019 (05:31)

We are so fortunate to live in such a great county. We came across this powerful Veterans Day video online and wanted to share it. This video was not produced by ConEquip Parts. . Call 716-246-0030

OnAir Post: Veterans

News

PBS NewsHour – November 11, 2023 (06:29)

An estimated 15 percent of veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan suffer from PTSD and depression. For some, it’s the invisible wounds that take the greatest toll. A program at a farm in Connecticut is helping ease those struggles by connecting veterans with horses. Pamela Watts of Rhode Island PBS Weekly reports

Marine Corps veteran Juliana Mercer discusses her work to support veterans, using psychedelic therapies for PTSD symptoms and more as this month’s guest on The American Legion’s Be the One podcast. Through this series, The American Legion aims to continue to raise awareness about its mission to reduce the rate of veteran suicide through Be the One.

Throughout her 16-year military career, Mercer served in and out of war zones, including deployments to Iraq and Afghanistan. She also spent four years providing holistic support to injured Marines recovering at the Wounded Warrior Battalion in San Diego. Her initial role was to determine what the injured Marines needed in terms of support services and make that connection. Later, she would “do everything holistic, non-medical, to take care of them and help them figure out how to live their lives post-injury.”

That experience helped her discover her passion and also transition into the nonprofit space after her service.

About

Overview

Access to Healthcare

- Long wait times for appointments

- Lack of access to specialized care, especially in rural areas

- High cost of prescription medications

- Mental health disparities

Housing and Homelessness

- High rates of homelessness among veterans

- Insufficient affordable housing options

- Difficulties navigating bureaucratic hurdles for VA housing assistance programs

Economic Security

- Unemployment and underemployment

- Low wages and poverty

- Lack of access to job training and retraining programs

- Financial exploitation and scams

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

- High rates of PTSD, depression, and anxiety

- Substance abuse disorders

- Lack of access to evidence-based mental health treatments

- Stigma associated with mental illness

Education and Training

- Difficulty transitioning from military to civilian education

- Lack of employer recognition for military experience and skills

- Limited access to VA education benefits

Social Support and Isolation

- Loneliness and social isolation

- Lack of peer support or community connections

- Difficulties building relationships outside of the military

Justice and Legal Issues

- Incarceration and recidivism

- Barriers to employment and housing due to criminal records

- Lack of access to legal assistance

VA Claims and Benefits

- Delays in processing disability claims

- Denials or inadequate compensation for injuries or illnesses

- Lack of transparency and accountability in VA claims adjudications

Suicide Prevention

- High rates of suicide among veterans

- Lack of access to timely and effective mental health care

- Stigma associated with seeking help

Advocacy and Outreach

- Need for increased awareness and education about veteran issues

- Improved coordination and collaboration among veteran service organizations

- Strengthened advocacy efforts to influence policy and funding decisions

Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation

Party positions

Republican Party platform: In 2020, the Republican Party decided not to write a platform for that presidential election cycle, instead simply expressing its support for Donald Trump’s agenda.

- Go here to see a PDF on 2016 Republican Platform.

- Go to this Wikipedia entry to read “Political positions of Donald Trump”.

Democratic Party platform:

- Go here to read the Democratic Party’s plaform on the DNC’s website.

- Go to this Wikipedia entry to read the”Political positions of the Democratic Party”

Democratic Party

- Expanding access to healthcare: Democrats support expanding access to healthcare for veterans, including mental health services and long-term care.

- Improving benefits: Democrats support increasing disability benefits, education benefits, and other benefits for veterans.

- Ending homelessness among veterans: Democrats support programs to end homelessness among veterans, including housing vouchers and supportive services.

- Reducing suicide rates: Democrats support programs to reduce suicide rates among veterans, including mental health screenings and crisis intervention services.

- Honoring veterans: Democrats support initiatives to honor veterans, such as the creation of a national veterans memorial and the expansion of the VA cemetery system.

Republican Party

- Privatizing the VA: Republicans support privatizing the VA, arguing that it would improve efficiency and reduce costs.

- Reducing benefits: Republicans support reducing benefits for veterans, arguing that it would save taxpayer money.

- Limiting access to healthcare: Republicans support limiting access to healthcare for veterans, arguing that it would reduce government spending.

- Opposing gun control: Republicans oppose gun control measures, arguing that they would infringe on the rights of veterans.

- Supporting veterans’ businesses: Republicans support policies that benefit veterans’ businesses, such as tax breaks and government contracting preferences.

Independent/Other

- Progressive Party: Progressives support expanding benefits for veterans, increasing access to healthcare, and ending homelessness among veterans.

- Libertarian Party: Libertarians support privatizing the VA, reducing benefits for veterans, and limiting access to healthcare.

- Green Party: Greens support expanding benefits for veterans, increasing access to healthcare, and ending homelessness among veterans.

Source: Government Agencies Nonprofit Organizations Healthcare and Mental Health Employment and Education Legal Assistance Other Resources Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) 2. Department of Defense (DoD) 3. Department of Labor (DOL) 4. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) 5. Department of Justice (DOJ) 6. Department of Agriculture (USDA) 7. Department of the Interior (DOI) 8. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation Senate Committees House of Representatives Committees Joint Committees Subcommittees Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation House of Representatives Senate Additional Caucuses Source: Google Search + Gemini + onAir curation The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers and outpatient clinics located throughout the country. Non-healthcare benefits include disability compensation, vocational rehabilitation, education assistance, home loans, and life insurance. The VA also provides burial and memorial benefits to eligible veterans and family members at 135 national cemeteries. While veterans’ benefits have been provided by the federal government since the American Revolutionary War, a veteran-specific federal agency was not established until 1930, as the Veterans’ Administration. In 1982, its mission was expanded to include caring for civilians and people who were not veterans in case of a national emergency.[2] In 1989, the Veterans’ Administration became a cabinet-level Department of Veterans Affairs. The president appoints the secretary of veterans affairs, who is also a cabinet member, to lead the agency.[3][4] As of June 2020, the VA employed 412,892 people[5] at hundreds of Veterans Affairs medical facilities, clinics, benefits offices, and cemeteries. In Fiscal Year 2016 net program costs for the department were $273 billion, which includes the VBA Actuarial Cost of $106.5 billion for compensation benefits.[6][7] The long-term “actuarial accrued liability” (total estimated future payments for veterans and their family members) is $2.491 trillion for compensation benefits; $59.6 billion for education benefits; and $4.6 billion for burial benefits.[8] The history and evolution of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs are inextricably intertwined and dependent on the history of America’s wars, as wounded soldiers are the population the VA cares for. The list of wars involving the United States from the American Revolutionary War to the present totals ninety-nine wars. The majority of the United States military casualties of war, however, occurred in the following eight wars: American Revolutionary War (est. 8,000), American Civil War (218,222), World War I (53,402), World War II (291,567), Korean War (33,686), Vietnam War (47,424), Iraq War (3,836), and the War in Afghanistan (1,833). It is these wars that have primarily driven the mission and evolution of the VA. The VA maintains a detailed list of war wounded, as it is this population that comprises the VA care system.[9] The Continental Congress of 1776 encouraged enlistments during the American Revolutionary War by providing pensions for soldiers who were disabled. Direct medical and hospital care given to veterans in the early days of the U.S. was provided by the individual states and communities. In 1811, the first domiciliary and medical facility for veterans was authorized by the federal government but not opened until 1834. In the 19th century, the nation’s veterans assistance program was expanded to include benefits and pensions not only for veterans but also their widows and dependents.[10] After the end of the American Civil War in 1865, many state veterans’ homes were established. Since domiciliary care was available at all state veterans homes, incidental medical and hospital treatment was provided for all injuries and diseases, whether or not of service origin. Indigent and disabled veterans of the Civil War, Indian Wars, Spanish–American War, and Mexican Border periods, as well as discharged regular members of the Armed Forces, were cared for at these homes.[10] During this period, two of the three predecessors of the Veterans’ Administration were established: the Bureau of Pensions in 1832 and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in 1865.[10] Congress established a new system of veterans benefits when the United States entered World War I in 1917. Included were programs for disability compensation, insurance for service members and veterans, and vocational rehabilitation for the disabled.[10] The Veterans’ Bureau was established in August 1921, absorbing the War Risk Bureau and the Rehabilitation Division of the Federal Board for Vocational Education.[11] In 1922,[12] it gained a large number of veterans’ hospital facilities from the Public Health Service, most of which had been recently established on former U.S. Army bases.[10][13] By the 1920s, the various benefits were administered by three different federal agencies: the Veterans’ Bureau, the Bureau of Pensions, and the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers.[10] The establishment of the Veterans’ Administration came in 1930, when Congress authorized the president to “consolidate and coordinate Government activities affecting war veterans”. The three component agencies became bureaus within the Veterans’ Administration. Brigadier General Frank T. Hines, who directed the Veterans’ Bureau for seven years, was named the first Administrator of Veterans Affairs, a job he held until 1945.[10] The close of World War II resulted in not only a vast increase in the veteran population but also a large number of new benefits enacted by Congress for veterans of the war.[10] In addition, during the late 1940s, the VA had to contend with aging World War I veterans. During that time, “the clientele of the VA increased almost fivefold with an addition of nearly 16,000,000 World War II veterans and approximately 4,000,000 World War I veterans.”[14][15][16] Prior to World War II, in response to scandals at the Veterans Bureau, programs that cared for veterans were centralized in Washington, D.C. This centralization caused delays and bottlenecks as the agency tried to serve World War II veterans. As a result, the VA went through a decentralization process, giving more authority to the field offices.[17] The World War II GI Bill was signed into law on June 22, 1944, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[18] “The United States government began serious consolidated services to veterans in 1930. The GI Bill of Rights, which was passed in 1944, had more effect on the American way of life than any other legislation—with the possible exception of the Homestead Act.”[19] Further educational assistance acts were passed for the benefit of veterans of the Korean War. The Department of Veterans Affairs Act of 1988 (Pub. L. 100–527) changed the former Veterans’[20] Administration, an independent government agency established in 1930 into a Cabinet-level Department of Veterans Affairs. It was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan on October 25, 1988, but came into effect under the term of his successor, George H. W. Bush, on March 15, 1989. The reform period of 1995 to 2000 saw the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) dramatically improve care access, quality, and efficiency. This was achieved by leveraging its national integrated electronic health information system (VistA) and in so doing, implementing universal primary care, which increased patients treated by 24%, had a 48% increase in ambulatory care visits, and decreased staffing by 12%. By 2000, the VHA had 10,000 fewer employees than in 1995 and a 104% increase in patients treated since 1995, and had managed to maintain the same cost per patient-day, while all other facilities’ costs had risen by over 30% to 40% during the same period.[citation needed] Authored by Senator Jim Webb, the Post-9/11 Veterans Educational Assistance Act of 2008 doubled the GI Bill’s college benefits and provided a 13-week extension to federal unemployment benefits. The new GI Bill more than doubled the value of the benefit from $40,000 to about $90,000. In-state public universities are essentially covered to provide full scholarships for veterans under the new education package. For those veterans who served at least three years, a monthly housing stipend was also added to the law.[21] Congress and President Barack Obama extended the new GI Bill in August 2009 at a cost of roughly $70 billion over the next decade. The Department of Defense (DoD) allows individuals who, on or after August 1, 2009, have served at least six years in the Armed Forces and who agree to serve at least another four years in the U.S. Armed Forces to transfer unused entitlement to their surviving spouse. Service members reaching 10-year anniversaries could choose to transfer the benefit to any dependents, such as their spouse or children.[22] In May 2014, critics of the VA system reported problems with scheduling timely access to medical care. In May 2014, a retired doctor said that veterans died because of delays in getting care at the Phoenix, Arizona, Veterans Health Administration facilities.[23][24] An investigation of delays in treatment in the Veterans Health Administration system conducted by the Veterans Affairs Inspector General of 3,409 veteran patients found that there were 28 instances of clinically significant delays in care associated with access or scheduling. Of these 28 patients, six were deceased.[25] The same OIG report stated that the Office of Investigations had opened investigations at 93 sites of care in response to allegations of wait time manipulations, and found that wait time manipulations were prevalent throughout the VHA. On May 30, 2014, Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki resigned from office due to the fallout from the scandal,[26] saying he could not explain the lack of integrity among some leaders in VA healthcare facilities. “That breach of integrity is irresponsible, it is indefensible, and unacceptable to me. I said when this situation began weeks to months ago that I thought the problem was limited and isolated because I believed that. I no longer believe it. It is systemic. I was too trusting of some and I accepted as accurate reports that I now know to have been misleading with regard to patient wait-times,” Shinseki said in a statement.[27] In September 2017, the VA declared its intent to abolish a 1960s conflict of interest rule prohibiting employees from owning stock in, performing service for, or doing any work at for-profit colleges; arguing that, for example, the rule prohibits VA doctors from teaching veterans at for-profit universities with special advantages for veterans.[28] In 2018, the VA instead established a process for employees to seek waivers of the policy based on individual circumstances.[29] In 2023, the VA adopted a new mission statement: “To fulfill President Lincoln’s promise to care for those who have served in our nation’s military and for their families, caregivers, and survivors.” The VA’s previous mission statement, established in 1959, was, “To fulfill President Lincoln’s promise ‘to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan’ by serving and honoring the men and women who are America’s veterans.”[30] The VA’s primary function is to support veterans in their time after service by providing benefits and support. Providing care for non-veteran civilian or military patients in case hospitals overflowed in a crisis was added as a role by Congress in 1982, and became known as the VA’s “fourth mission” (besides the three missions of serving veterans through care, research, and training).[31][2] It can provide medical services (reimbursed from other federal agencies) to the general public for major disasters and emergencies declared by the President of the United States, and when the Secretary of Health and Human Services activates the National Disaster Medical System.[31][32] During disasters and health emergencies, requests for VA assistance are made by state governors to the Federal Emergency Management Agency or the Department of Health and Human Services, which then relay approved requests to the VA.[33][34] The VA is also allowed to provide paid medical care on an emergency basis to non-veterans.[35] On March 27, 2020, the VA made public its COVID-19 response plan within its medical facilities to protect veterans, their families, and staff.[36] One initiative in the department is to prevent and end veterans’ homelessness.[37] The VA works with the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness to address these issues. The USICH identified ending veterans’ homelessness by 2015 as a primary goal in its proposal Opening Doors: Federal Strategic Plan to Prevent and End Homelessness, released in 2010; amendments to the 2010 version made in 2015 include a preface written by U.S. Secretary of Labor Thomas E. Perez that cites a 33% reduction in veteran homelessness since the creation of the Opening Doors initiative.[38] The prominent role of the Department of Veterans Affairs and its joined up approach to veteran welfare are such that they have been deemed to distinguish the US response to veteran homelessness internationally.[39] The General Services Administration (GSA) has delegated authority to the VA to procure medical supplies under the VA Federal Supply Schedules Program for both the VA itself and other government agencies.[40] The Department of Veterans Affairs is headed by the secretary of veterans affairs, appointed by the President with the advice and consent of the Senate. The secretary of veterans affairs is Denis McDonough who was selected by President Joe Biden and sworn in by Vice President Kamala Harris on February 9, 2021.[41] The deputy secretary of veterans affairs position is currently vacant with the retirement of Thomas G. Bowman on June 15, 2018.[42] The third listed executive on the VA’s official web site is its Chief of Staff (currently Pamela J. Powers);[43] the Chief of Staff position does not require Senate confirmation. In addition to Secretary and Deputy Secretary, the VA has ten more positions requiring presidential appointment and Senate approval. The department has three main subdivisions, known as administrations, each headed by an undersecretary: There are Assistant Secretaries of Veteran Affairs for: Congressional and Legislative Affairs; Policy and Planning; Human Resources and Administration; and Operations, Security and Preparedness. Other Senate-approved presidential nominees at the VA include the Chief Financial Officer; Chairman of the Board of Veterans’ Appeals; General Counsel; and Inspector General.[44] The VA employs[when?] 377,805 people, of whom 338,205 are nonseasonal full-time employees.[45] The American Federation of Government Employees represents 230,000 VA employees,[46] with VA matters addressed in detail by the National VA Council.[47] The VA, through its Veterans Benefits Administration (VBA), provides a variety of services for veterans, including disability compensation, pension, education, home loans, life insurance, vocational, rehabilitation, survivors’ benefits, health care, and burial benefits.[48] The Department of Labor (DOL) provides job development and job training opportunities for disabled and other veterans through contacts with employers and local agencies. In 1973, the Veterans Administration assumed responsibility for the National Cemetery System (NCS), with the exception of Arlington National Cemetery, which was transferred from the Department of the Army. This was made official by Public Law 93-43, also known as the National Cemeteries Act of 1973. Five years later, Congress established the State Cemetery Grants Program under Public Law 95-476. The National Cemetery Administration now administers this program, which provides assistance to states and U.S. territories in establishing, expanding, and improving veterans cemeteries.[49] As part of its operations, the VA marks graves in national and state cemeteries (and the graves of veterans in private cemeteries upon request), and manages the State Cemetery Grants Program. The VA’s National Cemetery Administration oversees 131 national cemeteries in 39 states (including Puerto Rico), along with 33 soldier lots and monument sites. There are two national cemeteries maintained by the Department of the Army: Arlington National Cemetery and the U.S. Soldiers’ & Airmen’s Home National Cemetery. Additionally, many states have established their own state veterans cemeteries. The American Battle Monuments Commission manages 25 overseas military cemeteries that serve as the final resting places for almost 125,000 American war dead. It also memorializes over 94,000 U.S. servicemen and women on Tablets of the Missing, and through 25 memorials, monuments, and markers. Finally, the National Park Service maintains 14 national cemeteries. The Center for Women Veterans (CWA) was established within the Department of Veterans Affairs by Public Law 103-446 in November 1994.[50] The Center’s mission is to: Center for Women Veterans activities include monitoring and coordinating delivery of benefits and services to women veterans; coordinating with Federal, state, and local agencies and organizations and non-government partners which serve women veterans; serving as a resource and referral center for women veterans, their families, and their advocates; educating VA staff on women’ military contributions; ensuring that outreach materials portray and target women veterans; promoting recognition of women veterans’ service with activities and special events; and coordinating meetings of the Advisory Committee on Women Veterans. CWA has held summits and forums for female veterans and created social media campaigns and exhibits to highlight women’s military service. CWA offers a Women Veterans Call Center (1-855-829-6636) to assist female U.S. military veterans with VA services and resources.[51] In 2018, the Center for Women Veterans launched the “I Am Not Invisible” photography project, featuring individual portraits, to highlight and represent the contributions, needs, and experiences of America’s two million women veterans.[52] The VA categorizes veterans into eight priority groups and several additional subgroups, based on factors such as service-connected disabilities, and their income and assets (adjusted to local cost of living).[53] Veterans with a 50% or higher service-connected disability as determined by a VA regional office “rating board” (e.g., losing a limb in battle, PTSD, etc.) are provided comprehensive care and medication at no charge.[54] Veterans with lesser qualifying factors who exceed a pre-defined income threshold have to make co-payments for care for non-service-connected ailments and prescription medication.[dubious ] VA dental and nursing home care benefits are more restricted.[citation needed] Reservists and National Guard personnel who served stateside in peacetime settings or have no service-related disabilities generally do not qualify for VA health benefits.[55] The VA’s budget has been pushed to the limit in recent years[when?] by the War on Terrorism.[56] In December 2004, it was widely reported that VA’s funding crisis had become so severe that it could no longer provide disability ratings to veterans in a timely fashion.[57] This is a problem because until veterans are fully transitioned from the active-duty TRICARE healthcare system to VA, they are on their own with regard to many healthcare costs.[original research?] The VA’s backlog of pending disability claims under review (a process known as “adjudication”) peaked at 421,000 in 2001, and bottomed out at 254,000 in 2003, but crept back up to 340,000 in 2005.[58] Today’s[when?] backlog numbers are much lower at 69,626. These numbers are released every Monday.[59] No copayment is required for VA services for veterans with military-related medical conditions. VA-recognized service-connected disabilities include problems that started or were aggravated due to military service. Veteran service organizations such as the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Disabled American Veterans, as well as state-operated Veterans Affairs offices and County Veteran Service Officers (CVSO), have been known to assist veterans in the process of getting care from the VA. In his budget proposal for fiscal year 2009, President George W. Bush requested $38.7 billion—or 86.5% of the total Veterans Affairs budget—for veteran medical care alone.[citation needed] In the 2011 Costs of War report from Brown University, researchers projected that the cost of caring for veterans of the War on Terror would peak 30–40 years after the end of combat operations. They also predicted that medical and disability costs would ultimately total between $600 billion and $1 trillion for the hundreds of thousands treated by the Department of Veterans Affairs.[60] In a 2015 Center for Effective Government analysis of 15 federal agencies which receive the most Freedom of Information Act (United States) (FOIA) requests (using 2012 and 2013 data, the most recent years available), the VA earned a D by scoring 64 out of a possible 100 points, i.e. did not earn a satisfactory overall grade, for facilitating FOIA requests.[61] Websites

DEPARTMENT & AGENCIES

Departments

Agencies

Committees & Caucuses

Committees

Caucuses

More Information

Nonpartisan Organizations

“United States Department of Veterans Affairs” (Wiki)

Contents

History

Origins

Consolidation into Veterans’ Administration

World War II

Promotion to Department of Veterans Affairs

Functions

Organization

Veterans Benefits Administration

National Cemetery Administration

Center for Women Veterans

Costs for care

Freedom of Information Act processing performance

Related legislation

Proposed

See also

Notes and references

VA expends a substantial amount of its budgetary resources on medical care for Veterans and also disburses large cash amounts for Veteran’s compensation and education benefits programs.

![]() This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.OIG examined the Electronic Health Records (EHRs) and other information for the 3,409 veteran patients and identified 28 instances of clinically significant delays in care associated with access or scheduling. Of these 28 patients, 6 were deceased. In addition, we identified 17 cases of care deficiencies that were unrelated to access or scheduling. We also found problems with access to care for patients requiring Urology Services. As a result, Urology Services at PVAHCS will be the subject of a subsequent report. The 45 cases discussed in this report reflect unacceptable and troubling lapses in followup, coordination, quality, and continuity of care. The VA OIG Office of Investigations opened investigations at 93 sites of care in response to allegations of wait time manipulations. While most are still ongoing, these investigations confirmed wait time manipulations were prevalent throughout VHA.

External links

![]()