Summary

Mission:

The Senate Select Committee on Ethics is a select committee of the United States Senate charged with dealing with matters related to senatorial ethics.

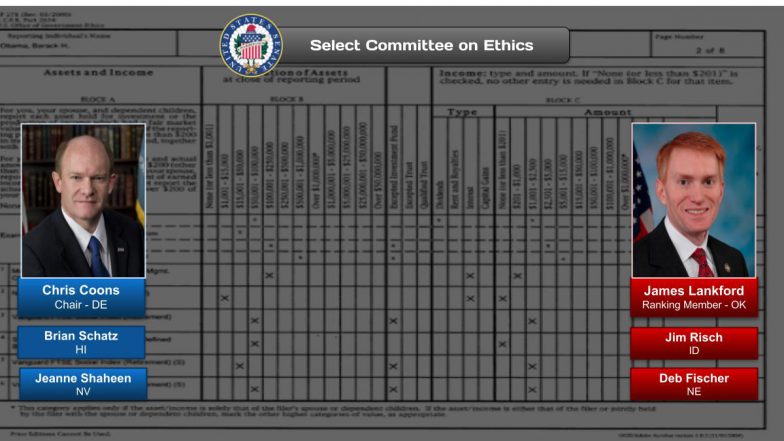

Democratic Members (Majority):

Chris Coons, Delaware, Chair

Brian Schatz, Hawaii

Jeanne Shaheen, New Hampshire

Republican Members (Minority):

James Lankford, Oklahoma, Vice Chair

Jim Risch, Idaho

Deb Fischer, Nebraska

Featured Video:

How the Senate ethics committee investigates

OnAir Post: Select Committee on Ethics

News

Majority Press Releases and news can be found here at the committee website.

Minority Press Releases and news can be found here at the committee website.

Gotham Gazette, – August 27, 2021

Looking over the scandal-pocked landscape of Albany in the wake of former Governor Andrew Cuomo’s resignation, lawmakers in the State Senate set their sights this week on the dysfunctional Joint Commission on Public Ethics, the state’s ethics watchdog often criticized for its apparent lack of independence and bite.

At a Senate ethics committee hearing Wednesday, senators on both sides of the aisle tore into JCOPE’s executive director, Judge Sanford Berland, over the rules and practices dictating the body’s decision-making and confidentiality, particularly surrounding an alleged 2019 illegal leak of a closed-doors vote regarding whether the agency should investigate one of Cuomo’s former top aides. On Thursday, JCOPE commissioners voted to refer that matter to New York Attorney General Letitia James for an investigation. JCOPE also sent James a criminal inquiry into whether the state inspector general’s investigation into the leak was adequate or if it amounted to a ‘cover up.’

About

Jurisdictional Authorities

Source: Committee website

History

The following is an excerpt from The Senate Select Committee on Ethics: A Brief History of Its Evolution and Jurisdiction, Mildred L. Amer, Congressional Research Service, The Library of Congress (March 26, 2008), pp. 4-7. Internal citations have been omitted.

Creation of the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct

Prior to 1964, there were no congressional ethics committees or formal rules governing the conduct of Members, officers, and employees of either house of Congress; nor was there a consistent approach to the investigation of alleged misconduct. When allegations were investigated, the investigation was usually done by a special or select committee created for that purpose. Sometimes, however, allegations were considered by the House or Senate without prior committee action.

Traditionally, the Senate and the House of Representatives have exercised their powers of self discipline with caution. According to Senate Historian Richard Baker, “[f]or nearly two centuries, a simple and informal code of behavior existed. Prevailing norms of general decency served as the chief determinants of proper legislative conduct.” Baker further noted that for most of its history, “Congress has chosen to deal, on a case-by-case basis, only with the most obvious acts of wrongdoing, those clearly ‘inconsistent with the trust and duty of a member.’”

Increasing attention to congressional ethics began in the 1940s, when concern was first expressed about the lack of financial disclosure requirements for the three branches of government. There was also public criticism about Members of Congress supplementing their salaries with income from speeches and other outside activities. Senator Wayne Morse, the first Member to introduce public financial disclosure legislation, defended Members’ right to earn outside income, but believed that the American people were entitled to know about their sources of income. Senator Morse’s 1946 resolution (S. Res. 306) would have required Senators to file annual public financial disclosure reports. It was predicated “upon the very sound philosophical principle enunciated by Plutarch that [Members of Congress just as] Caesar’s wife must be above suspicion.”

Senator Morse continued to introduce his measure through the 1960s, ultimately expanding it to include all three branches of government, and gaining support from Senators Paul Douglas and Clifford Case. During the 1950s and early 1960s, there were various unsuccessful attempts to create joint or select congressional committees to adopt and monitor codes of official conduct for Members and employees of the Senate.

Momentum for reform grew after Robert G. (Bobby) Baker, Secretary to the Senate Democratic Majority, resigned from his job in October 1963, following allegations that he had misused his official position for personal financial gain. For the next year and a half, the Senate Rules and Administration Committee held hearings to investigate the business interests and activities of Senate officials and employees in order to ascertain what, if any, conflicts of interest or other improprieties existed and whether any additional laws or regulations were needed. The committee recognized that serious allegations had been made against a former employee, and that no specific rules or regulations governed the duties and scope of activities of Members, officers, or employees of the Senate.

In its first report, the Senate Rules Committee characterized many of Baker’s outside activities as being in conflict with his official duties and made several recommendations, including adoption of public financial disclosure rules and other guidelines for Senate employees.

Subsequently, as part of its conclusion of the Baker case, the Rules Committee held additional hearings on proposals advocating a code of ethics in conjunction with a pending pay raise, the creation of a joint congressional ethics committee to write an ethics code, and the adoption of various rules requiring public disclosure of personal finances by Senators and staff and the disclosure of ex parte communications. Additions to the Senate rules — calling for public financial disclosure reports and more controls on staff involvement in Senate campaign funds — were then introduced to implement the committee’s recommendations.

In the report on the proposed additions to Senate rules, Senator John Sherman Cooper, a member of the Rules Committee, discussed the committee’s rejection of his proposal for the establishment of a select committee on standards and conduct. The proposed committee would have been empowered to receive and investigate complaints of unethical activity, as well as to propose rules and make recommendations to the Senate on disciplinary action.

To implement the proposed new Senate rules, the Committee on Rules and Administration reported a measure granting itself authority to investigate infractions of all Senate rules and to recommend disciplinary action. On July 24, 1964, during debate on the proposed new ethics rules (S. Res. 337), and a resolution (S. Res. 338) to give the Rules Committee additional authority, the Senate adopted a substitute proposal by Senator Cooper to establish a permanent, bipartisan Senate Select Committee on Standards and Conduct. The Senate chose to create a bipartisan ethics committee instead of granting the Rules Committee disciplinary authority, in part, because of the difficulties in the Baker investigation.

The new select committee was similar to the one Senator Cooper had advocated during several stages of the Bobby Baker investigation. The Senator had declared that, “one of the greatest duties of such a committee would be to have the judgment to know what it should investigate and what it should not.” Moreover, with the creation of this committee, an internal disciplinary body was established in Congress for the first time on a continuing basis.

The six members of the new committee were not appointed until a year later, in July 1965, however, because of the Senate leadership’s desire to wait until the Rules Committee had completed the Baker investigation. In October 1965, the committee elected a chairman and vice chairman, appointed its first staff, and began developing standards of conduct for the Senate.

Creation of the Select Committee on Ethics

Although the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct undertook several investigations from 1969 to 1977, it was sometimes characterized as “antiquated,” “do-little,” or as a “watchdog without teeth.” Moreover, the Senate ethics code, which the committee wrote in 1968, was often viewed as ineffective.

In 1976, a select committee, created to study the Senate committee system, recommended that the functions of the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct should be placed under the Senate Rules and Administration Committee. The Rules Committee, however, rejected the idea and instead recommended establishment of a newly constituted bipartisan ethics committee to demonstrate to the public the “seriousness with which the Senate views congressional conduct.” In response, the permanent Select Committee on Ethics was created in 1977 to replace the Select Committee on Standards and Conduct. Initially, membership on the new select committee was limited to six years. Two years later, the six-year limitation was removed.

Source: Committee website

Contact

Email: Contacting the Committee

Locations

Select Committee on Ethics

220 Hart Building, United States Senate, Washington, DC 20510

Phone: (202) 224-2981

Web Links

More Information

Wikipedia

Contents

The U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics is a select committee of the United States Senate charged with dealing with matters related to senatorial ethics. It is also commonly referred to as the Senate Ethics Committee. Senate rules require the Ethics Committee to be evenly divided between the Democrats and the Republicans, no matter who controls the Senate, although the chairman always comes from the majority party. The leading committee member of the minority party is referred to as Vice Chairman rather than the more common Ranking Member.

History

The Senate Select Committee on Standards and Conduct was first convened in the 89th Congress (1965–66) and later replaced by the Senate Select Committee on Ethics in the 95th Congress (1977–78).

Membership

Pursuant to Senate Rule 25, the committee is limited to six members, and is equally divided between Democrats and Republicans. This effectively means that either party can veto any action taken by the committee.[1]

Current membership

| Majority[2] | Minority[3] |

|---|---|

|

|

Chairs

List of chairs of the Senate Select Committee on Ethics

| Chair | Party | State | Term |

|---|---|---|---|

| John C. Stennis | D | Mississippi | 1965–1975 |

| Howard Cannon | D | Nevada | 1975–1977 |

| Adlai Stevenson III | D | Illinois | 1977–1980 |

| Howell Heflin | D | Alabama | 1980–1981 |

| Malcolm Wallop | R | Wyoming | 1981–1983 |

| Ted Stevens | R | Alaska | 1983–1985 |

| Warren Rudman | R | New Hampshire | 1985–1987 |

| Howell Heflin | D | Alabama | 1987–1992 |

| Terry Sanford | D | North Carolina | 1992–1993 |

| Richard Bryan | D | Nevada | 1993–1995 |

| Mitch McConnell | R | Kentucky | 1995–1997 |

| Bob Smith | R | New Hampshire | 1997–1999 |

| Pat Roberts | R | Kansas | 1999–2001 (ended January 3) |

| Vacant | — | — | 2001 (January 3–20) |

| Pat Roberts | R | Kansas | 2001 (January 20 – June 6) |

| Harry Reid | D | Nevada | 2001–2003 (started June 6, 2001) |

| George Voinovich | R | Ohio | 2003–2007 |

| Barbara Boxer | D | California | 2007–2015 |

| Johnny Isakson | R | Georgia | 2015–2019 |

| James Lankford | R | Oklahoma | 2019–2021 |

| Chris Coons | D | Delaware | 2021–present |

Historical committee rosters

110th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

111th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

112th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: 2011 Congressional Record, Vol. 157, Page S557

113th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: 2011 Congressional Record, Vol. 157, Page S557

114th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: 2013 Congressional Record, Vol. 159, Page S296

115th Congress

Members of the Senate Select Committee on Ethics, 115th Congress[4]

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

116th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

117th Congress

| Majority | Minority |

|---|---|

|

|

See also

References

- ^ “U.S. Senate: Select Committee on Ethics”. www.senate.gov. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- ^ S.Res. 30 (118th Congress)

- ^ S.Res. 31 (118th Congress)

- ^ Straus, Jacob R. (January 31, 2017). “Appendices A and B”. Senate Select Committee on Ethics: A Brief History of Its Evolution and Jurisdiction (PDF) (Report). Congressional Research Service. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

External links

- U.S. Senate Select Committee on Ethics Official Website (Archive)

- Senate Ethics Committee. Legislation activity and reports, Congress.gov.