News

CNN, – March 10, 2022

In public statements and at international summits, Chinese officials have attempted to stake out a seemingly neutral position on the war in Ukraine, neither condemning Russian actions nor ruling out the possibility Beijing could act as a mediator in a push for peace.

But while its international messaging has kept many guessing as to Beijing’s true intentions, much of its domestic media coverage of Russia’s invasion tells a wholly different story.

There, an alternate reality is playing out for China’s 1.4 billion people, one in which the invasion is nothing more than a “special military operation,” according to its national broadcaster CCTV; the United States may be funding a biological weapons program in Ukraine, and Russian President Vladimir Putin is a victim standing up for a beleaguered Russia.

MSNBC – March 10, 2022 (05:20)

Joe Scarboutgh and the Morning Joe panel discuss why Putin’s invasion of Ukraine is such a “nightmare” for China. The current global world order, Joe says, is something “the Chinese have maniacally been focused on dominating for 30 years, and now that they’re in the position where they can start dominating, Putin is setting it on fire.”

The Conversation, – March 10, 2022

Russia has few friends in the international community following its invasion of Ukraine. But China, which shares a 2,672-mile (4,300-kilometer) border with Russia, is among the handful of nations that has refused to condemn Vladimir Putin’s actions, while criticizing the West’s response to the crisis and its role in pushing tensions to a “breaking point.”

But Beijing hasn’t offered full-throated messages of support to Moscow over the war, instead calling for peace talks and “maximum restraint.” The Conversation asked Joseph Torigian, a specialist on Russia and China at American University who has a forthcoming book on power struggles in the Soviet Union and China after Stalin and Mao, to unpack what is behind Beijing’s delicate position on Ukraine.

What is behind China’s position on Russia and the war in Ukraine?

China’s President, Xi Jinping, said on March 8 that he was “pained” to see “flames of war reignited in Europe.” But China has been reticent to criticize Russia.

The Russian Foreign Ministry on Feb. 28, 2022, described China as one of Russia’s key remaining friends, and Moscow will hope that Beijing will continue to provide rhetorical and substantive assistance.

Beijing will be sensitive to Western attempts to foster tension in the relationship, and Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi recently described ties with Moscow as “rock solid.” He added that China and Russia “will always maintain strategic focus and steadily advance our comprehensive strategic partnership of coordination for a new era.”

China has carefully ensured that its own media remains pro-Russian and has even republished false reports by Russian state media.

Yet the invasion of Ukraine is problematic for Beijing. It is unclear how much economic help China can provide to Russia. And the Chinese government will not put the country’s own financial interests at stake in any significant way to help Russia avoid sanctions.

Meanwhile, China is also trying to preserve its reputation as a responsible stakeholder and protect its economic, trading and political ties to Europe. Underlying this, Xi met with his German and French counterparts on March 8, 2022, to discuss a diplomatic solution to the war in Ukraine.

Beijing’s balancing act – seen in its decision to abstain from a United Nations Security Council vote condemning the invasion – will grow harder to maintain the longer the fighting continues, especially as the Russian army resorts to even more brutal methods and the Russian economy continues to deteriorate.

What has been Beijing’s reaction to the sanctions on Russia?

Beijing has been critical of Western sanctions against Russia, and it certainly does not want to see a complete collapse of the Russian economy. Such an outcome could encourage instability in a neighboring state that Beijing sees as an important strategic partner.

But so far, China has not rushed to support the Russian Federation economically. China is very vulnerable to secondary sanctions – penalties levied against institutions with ties to the country under primary sanctions – and it is notable that some Chinese financial institutions have begun to distance themselves from the Russian economy.

Meanwhile, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, a development bank that China launched and in which it holds 27% of voting power, halted its work in Belarus and Russia in protest of the invasion of Ukraine.

What remains to be seen is whether China will use creative, less visible methods to help the Russia economy in a way that would not put its bigger institutions at risk of being accused of sanctions busting.

Beijing will also likely be drawing lessons about its own potential vulnerabilities to sanctions should China ever, like Russia, find itself provoking large-scale economic penalties from the West.

What role does anti-West feeling play in China-Russia relations?

Russia and China endured decades of rivalry and hostility during much of the Cold War. But a rapprochement decades in the making has picked up pace in recent years based in part in opposition to the West.

The governments of both countries hold similarly negative views about America’s role in Europe and Asia. They also share a distaste for Western democracy and a desire to make global public opinion more welcoming to autocracies.

But Washington is not the only factor pushing them together. In the 2000s, Russia and China finally fully resolved their long-running territorial dispute over their shared border. The two countries are also trading partners: Russia sells weapons, gas and oil to China, and China provides investment and consumer goods.

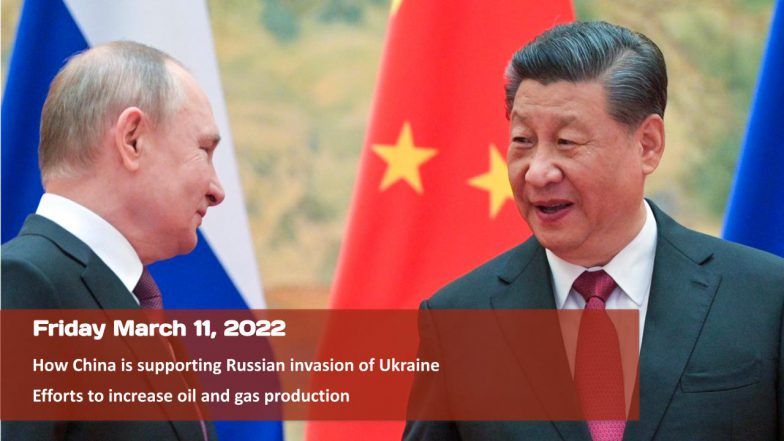

Close ties have been reflected at the highest level, with Putin and Xi developing a personal relationship they are eager to present to the world. In July 2021, Wang, China’s foreign minister, described Moscow and Beijing’s relationship as everything but an alliance yet also better than an alliance. And then, in February, Xi and Putin signed a joint declaration outlining their shared positions on a number of issues.

How significant was that statement, coming just before the invasion?

The timing of the joint declaration came on the eve of the Olympics in Beijing, and Putin’s presence at that event contrasted strongly with the absence of Western leaders, many of whom imposed a diplomatic boycott.

The document was signed at the height of pre-war tensions over Ukraine, and it included language criticizing America’s system of alliances in both Europe and Asia. It specifically outlined the countries’ joint opposition to any “further enlargement of NATO.”

There has also been some suggestion in Western media that the Chinese had been warned before that pact about a Russian invasion of Ukraine. The details of the conversation Putin and Xi had about Ukraine in Beijing are not fully known, but the joint statement certainly gave observers in the West cause to believe China’s behavior might have helped to enable Russian aggression.

Is there a role for China in ending the war?

China has floated the idea of playing some kind of mediating role, but what exactly it might mean remains unclear. Beijing is widely seen in the West as too pro-Russian, and it doesn’t have experience playing that kind of a role in Europe.

There is certainly some hope that China will put pressure on Russia to end the conflict. Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba said on March that he had received assurances that “China is interested in stopping this war,” adding: “Chinese diplomacy has sufficient tools to make a difference, and we count that it is already involved.”

Western policymakers have signaled to China that Beijing would face costs if it is seen to be an enabler of Russia’s continued aggression. And Putin may be sensitive to any change in Xi’s position. But China lacks the will and capability to force Russia to completely back down. And both sides have reason to try to manage whatever strains may exist for now.

CNN, – March 11, 2022

An intense, closely guarded diplomatic effort by a core team of Biden energy and national security officials to raise global oil production amid surging prices from Russia’s war in Ukraine has fostered a cautious sense of optimism inside the White House.

The two main targets of the effort, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, have had frosty relations with the US since Biden took office. Both countries are members of OPEC, the powerful bloc of 13 countries that together control 40% of global oil production. And both were on friendlier terms with the Trump administration.

But over the past month, US officials say progress has been made and there may be evidence the diplomatic work is starting to pay off.

March 11, 2022 – 12:00 pm (ET)

PBS NewsHour – March 10, 2022 (09:32)

March 11, 2022 – 2:00 pm (ET)

March 11, 2022 – 1:30 pm (ET)

Intercept, – March 11, 2022

The oil and gas industry won’t increase production because it’s enjoying the profits from high prices.

This week, as President Biden banned the import of Russian oil and gas, fuel prices skyrocketed, and pundits and Substack bros across the land repeated the company line we all know by heart now: We need to drill more and increase production.

It’s a rallying cry that makes no sense. On top of the fact that there’s no such thing as an “immediate” increase in oil and gas production, if anything this crisis is one more reason to speed up the transition away from fossil fuels. And in the meantime, since the industry is going to blame the government for everything anyway, a little intervention would actually be helpful here, not to help the oil and gas companies but to rein them in and actually help the American public.

During the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, Arab members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries imposed an embargo on exporting oil to the U.S. due to its support of Israel in the war. The result was rationing, miles-long lines at gas stations, a whole lot of headlines questioning our dependency on foreign oil, and ultimately a huge boom in energy efficiency and non-fossil energy in the U.S. The oil industry, of course, claimed that the shortages were all the government’s fault for refusing to let them drill more in the years preceding the embargo.

German Marshall Fund, – March 11, 2022

The resurgent Russia has posed many strategic challenges to Turkey since its war against Georgia in 2008.

Its involvement in the Syrian civil war and its annexation of Crimea in 2014 deepened these, yet Turkey has avoided being critical, forging instead a special relationship with Russia in areas ranging from the economy to tourism, energy, and the defense industry. Among other factors, a rather benign assessment of Russia and its intentions facilitated the emergence of this strategic relationship of dependence.

As Russia increased its pressure on Ukraine in recent months, many expected Turkey to sit on the fence and maintain its balancing act between the two countries. However, prior to NATO’s meeting on February 25 following the start of the invasion, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan urged a more determined stance by the alliance. Many analysts were far too dismissive of these remarks as a continuation of his rhetorical bashing of the West. While the duality in Erdoğan’s approach toward the West and his skepticism toward Western responsibility in the current crisis remain, his remarks reflected a deep watershed in Turkey’s assessment of its relations with Russia.

As the world wakes up to a new geopolitical reality, it would be naïve for Turkey to continue with a benign reading of the strategic environment and to seek a policy of neutrality between the warring parties. If Turkey’s previous encounters with Russia in Syria or developments since 2014 have not already done so, this war has laid bare Moscow’s encroachments in its sphere of interest. As the external security environment turns restrictive, the prospects of conducting foreign policy with domestic imperatives are weakened. Therefore, analyzing Turkey’s behavior in this crisis too much through the lenses of its domestic politics may be misleading and one should look at how systemic imperatives affect its strategic priorities. In a fundamentally altered international environment, the imperative to counter the risks posed by the new phase of Russian revisionism will be more decisive.

PBS NewsHour – March 11, 2022 (04:13)

President Biden and other leaders of the so-called G-7 on Friday revoked Russia’s “most favored nation” trade status, which will allow for large tariffs on Russian exports. This as Russia further cracked down on access to social media in the country. Special correspondent Ryan Chilcote joins Judy Woodruff from Moscow.

March 11, 2022