A citizen of a foreign country who wishes to work in the United States must first get the right visa. If the employment is for a fixed period, the applicant can apply for a temporary employment visa. There are 11 temporary worker visa categories. Most applicants for temporary worker visas must have an approved petition. The prospective employer must file the petition on behalf of the applicant. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) reviews the petition.

- In the ‘About’ section of this post is an overview of the issues or challenges, potential solutions, and web links. Other sections have information on relevant legislation, committees, agencies, programs in addition to information on the judiciary, nonpartisan & partisan organizations, and a wikipedia entry.

- To participate in ongoing forums, ask the post’s curators questions, and make suggestions, scroll to the ‘Discuss’ section at the bottom of each post or select the “comment” icon.

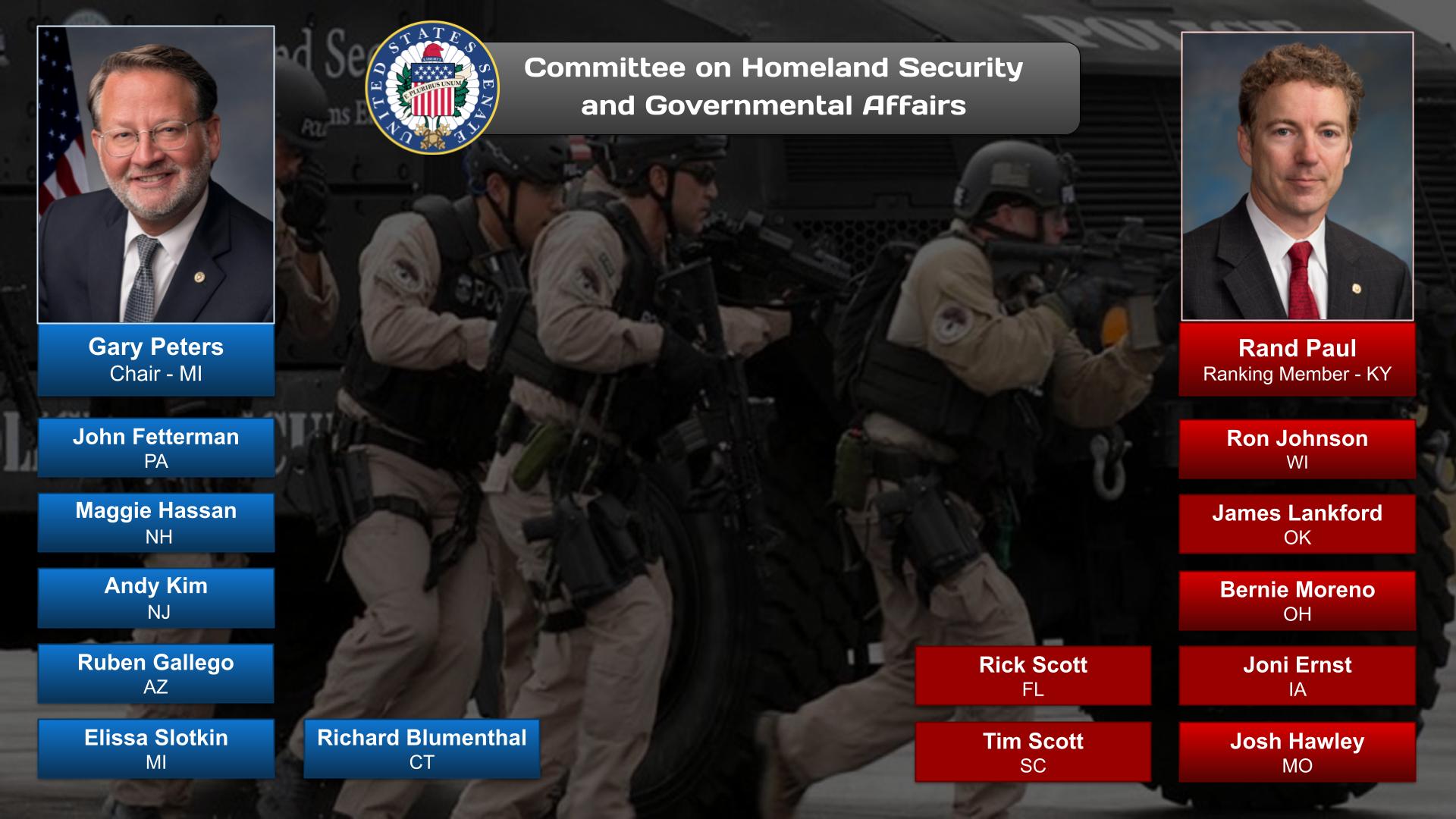

The Work Visas category has related posts on government agencies and departments and committees and their Chairs.

PBS NewsHour – 20/05/2021 (08:10)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X5lvR8tvImg

President Joe Biden has said that changing immigration law remains an important piece of his agenda. But the path to new legislation is complex and hardly clear. One of the biggest flashpoints in this debate are questions about undocumented workers and their role in the economy. Paul Solman dives into those questions for his latest report for “Making Sense.”

OnAir Post: Work Visas