Summary

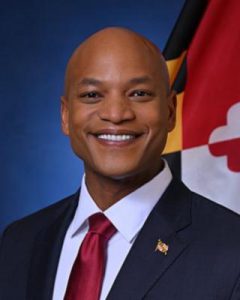

Current: Governor of State of Maryland since 2023

Affiliation: Democrat

History: Wes Moore is a combat veteran (2004 to 2014), bestselling author, small business owner, Rhodes Scholar and former CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation (2015 – 2021), one of the nation’s largest anti-poverty organizations.

In February 2006, Moore was named a White House Fellow to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. He later worked as an investment banker at Deutsche Bank in Manhattan and at Citibank from 2007 to 2012

Featured Quote: Moore has devoted his life’s work to a basic principle: no matter your start in life, you deserve an equal opportunity to succeed – a job you can raise a family on, a future you can look forward to.

Featured Video: State of the State Address with Maryland Governor Wes Moore (Streamed Feb. 1, 2023 … 1:14:01)

OnAir Post: Wes Moore – MD

News

Gov. Wes Moore is holding a press conference Thursday to provide updates on efforts underway following the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge in Baltimore. Moore will be joined by the Unified Command, U.S. Small Business Administrator Isabel Casillas Guzman, and federal and local elected leaders.

For Gov. Wes Moore of Maryland, it all comes back to service, no matter the location.

So it’s fitting that Moore on Saturday found himself in the military-and defense-heavy Hampton Roads region of Virginia as he stumped for Democratic candidates ahead of Tuesday’s critical legislative elections in the Commonwealth.

With all 140 seats in the legislature up for grabs, Moore made several stops across the state ahead of what will be a defining election for Virginia Gov. Glenn Youngkin. The Republican is looking to hold the House of Delegates and flip the state Senate in order to enact a conservative agenda in a state where Democrats have largely been ascendant over the past decade.

About

Source: Government site

Wes Moore is the 63rd Governor of the state of Maryland. He is Maryland’s first Black Governor in the state’s 246-year history, and is just the third African American elected Governor in the history of the United States.

Wes Moore is the 63rd Governor of the state of Maryland. He is Maryland’s first Black Governor in the state’s 246-year history, and is just the third African American elected Governor in the history of the United States.

Born in Takoma Park, Maryland, on Oct. 15, 1978, to Joy and Westley Moore, Moore’s life took a tragic turn when his father died of a rare, but treatable virus when he was just three years old. After his father’s death, his family moved to the Bronx to live with Moore’s grandparents before returning to Maryland at age 14.

Moore is a proud graduate of Valley Forge Military Academy and College, where he received an Associate’s degree in 1998, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the U.S. Army. Afterward, he went on to earn his Bachelor’s in international relations and economics at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he graduated Phi Beta Kappa.

While at Johns Hopkins, Moore interned in the office of former Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke. Moore was the first Black Rhodes Scholar in the history of Johns Hopkins University. As A Rhodes Scholar, he earned a Master’s in international relations from Wolfson College at Oxford.

In 2005, Moore deployed to Afghanistan as a captain with the 82nd Airborne Division, leading soldiers in combat. Immediately upon returning home, Moore served as a White House Fellow, advising on issues of national security and international relations.

In 2010, Moore wrote “The Other Wes Moore,” a story about the fragile nature of opportunity in America, which became a perennial New York Times bestseller. He went on to write other best-selling books that reflect on issues of race, equity, and opportunity, including his latest book “Five Days,” which tells the story of Baltimore in the days that followed the death of Freddie Gray in 2015.

Moore built and launched a Baltimore-based business called BridgeEdU, which reinvented freshman year of college for underserved students to increase their likelihood of long-term success. BridgeEdu was acquired by the Brooklyn-based student financial success platform, Edquity, in 2018.

It was Moore’s commitment to taking on our toughest challenges that brought him to the Robin Hood foundation, where he served for four years as CEO. During his tenure, the Robin Hood foundation distributed over $600 million toward lifting families out of poverty, including here in Maryland.

While the Robin Hood foundation is headquartered in New York City, Wes and his family never moved from their home in Baltimore.

Moore has also worked in finance with Deutsche Bank in London and with Citigroup in New York.

Moore and his wife Dawn Flythe Moore have two children – Mia, 12; and James, 9.

Personal

Full Name:

Westley ‘Wes’ Moore

Gender:

Male

Family: Wife: Dawn; 2 Children: Mia, James

Birth Date: 10/15/1978

Birth Place: Takoma Park, MD

Home City: Baltimore, MD

Education

MLitt, International Relations and Affairs, University of Oxford, 2001-2004

Bachelor’s, International Relations and Affairs, The John Hopkins University, 1998-2001

Office

100 State Circle, Annapolis, MD 21401

(410) 974-3901

By Phone

(410) 974-3901

1-800-811-8336

MD Relay 1-800-735-2258

By Mail

100 State Circle

Annapolis, Maryland

21401-1925

Contact

Email: Government

Locations

State Capital

100 State Circle

Annapolis, Maryland

21401-1925

Phone: 1-800-811-8336

Web Links

Videos

More from Moore: Governor Wes Moore Recaps The Week (October 30, 2023)

October 30, 2023 (02:40)

By: Governor Wes Moore

From discussion about Maryland’s economic growth to launching our Service Year program, our administration has been hard at work building a more inclusive Maryland where we love and uplift all our communities to build a stronger state.

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic |

| 217,524 | 32.4 | |

| Democratic |

| 202,175 | 30.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 141,586 | 21.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 26,594 | 4.0 | |

| Democratic |

| 25,481 | 3.8 | |

| Democratic |

| 24,882 | 3.7 | |

| Democratic |

| 13,784 | 2.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 11,880 | 1.8 | |

| Democratic |

| 4,276 | 0.6 | |

| Democratic |

| 2,978 | 0.4 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic |

| 1,293,944 | 64.53 | +21.02 | |

| Republican |

| 644,000 | 32.12 | -24.23 | |

| Libertarian |

| 30,101 | 1.50 | +0.93 | |

| Working Class |

| 17,154 | 0.86 | N/A | |

| Green |

| 14,580 | 0.73 | +0.25 | |

| Write-in | 5,444 | 0.27% | +0.19 | ||

| Total votes | 2,005,259 | 100.0 | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

New Legislation

Issues

Source: Campaign

Wes Moore is running for Governor because he believes no matter where you start in life, you deserve an equal opportunity to succeed. He has the experience, the vision, and the path to expand work, wages, and wealth for every family in Maryland.

More Information

Requests

Wikipedia

Contents

Westley Watende Omari Moore (born October 15, 1978) is an American politician, businessman, author, and former U.S. Army officer, serving as the 63rd governor of Maryland since 2023.

Moore was born in Maryland and raised primarily in New York. He graduated from Johns Hopkins University and received a master’s degree from Wolfson College, Oxford, as a Rhodes Scholar. After several years in the U.S. Army and Army Reserve, he became an investment banker in New York. Between 2010 and 2015, Moore published five books, including a young-adult novel. He served as CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation from 2017 to 2021.[1] Moore authored The Other Wes Moore and The Work. He also hosted Beyond Belief on the Oprah Winfrey Network (OWN), and was executive producer and a writer for Coming Back with Wes Moore on PBS.[2]

Moore is a member of the Democratic Party. He won the 2022 Maryland gubernatorial election, becoming Maryland’s first black governor and the third black person elected governor of any U.S. state.[a][4][5]

Early life and education

Moore was born in Takoma Park, Maryland in 1978, to William Westley Moore Jr., a broadcast news journalist,[6] and Joy Thomas Moore,[7] a daughter of immigrants from Cuba and Jamaica, and a news media professional.[8][9][10][11] His maternal grandfather, James Thomas, a Jamaican immigrant,[12] was the first black minister in the history of the Dutch Reformed Church.[13] His grandmother, Winell Thomas, a Cuban who moved to Jamaica before immigrating to the U.S., was a retired schoolteacher.[12] His grandmother’s stepfather was Chinese.[14]: 2:17

On April 15, 1982, when Moore was three years old,[15] his father died of acute epiglottitis.[16] In the summer of 1984, Moore’s mother took him and his two sisters to live in the Bronx, New York, with her parents.[12] His occasional babysitter was Kamala Harris‘ stepmother, Carol Kirlew.[17] Moore attended Riverdale Country School. When his grades declined and he became involved in petty crime, his mother enrolled him in Valley Forge Military Academy and College.[13][18] Moore’s family moved back to Maryland after his mother’s employer, the Annie E. Casey Foundation, relocated to Baltimore.[19]

In 1998, Moore graduated Phi Theta Kappa from Valley Forge with an associate degree, completed the requirements for the United States Army‘s early commissioning program, and was appointed a second lieutenant of Military Intelligence in the Army Reserve. He then attended Johns Hopkins University, from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a B.A. in international relations and economics in 2001.[20] At Johns Hopkins, he also played wide receiver for the Johns Hopkins Blue Jays football team for two seasons,[21][22] served as the chair of the university’s Men of the NAACP branch,[19] and was initiated into the Omicron Delta Kappa honor society, and Sigma Sigma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha.[23] In 1998 and 1999, Moore interned for Baltimore Mayor Kurt Schmoke.[24] He later became involved with the March of Dimes before serving in the Army.[25] He also interned at the United States Department of Homeland Security under Secretary Tom Ridge.[26]

After graduating, he attended Wolfson College, Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar, where he earned a master’s degree in international relations in 2004[27] and submitted a thesis titled Rise and Ramifications of Radical Islam in the Western Hemisphere.[28] He then served in the 82nd Airborne Division and was deployed to Afghanistan from 2005 to 2006,[29] attaining the rank of captain.[1][30] He left the Army in 2014.[28]

Career

by New America in January 2020

In February 2006, Moore was named a White House Fellow to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.[1][31][32] He later worked as an investment banker at Deutsche Bank in Manhattan[26] and at Citibank from 2007 to 2012[33] while living in Jersey City, New Jersey.[1][34] In 2009, Moore was included on Crain’s New York Business‘s “40 Under 40” list.[35]

In 2010, Moore founded a television production company, Omari Productions, to create content for networks such as the Oprah Winfrey Network, PBS, HBO, and NBC.[36] In May 2014, he produced a three-part PBS series, Coming Back with Wes Moore, which followed the lives and experiences of returning veterans.[37][38][39]

In 2014, Moore founded BridgeEdU, a company that provided services to support students in their transition to college.[40] Students participating in BridgeEdU paid $500 into the program with varying fees.[41] BridgeEdU was not able to achieve financial stability and was acquired by student financial services company Edquity in 2019, mostly for its database of clients.[42][43] A Baltimore Banner interview with former BridgeEdU students found that the short-lived company had mixed results.[43]

In September 2016, Moore produced All the Difference, a PBS documentary that followed the lives of two young African-American men from the South Side of Chicago from high school through college and beyond.[44][45] Later that month, he launched Future City, an interview-based talk show with Baltimore’s WYPR station.[46][47][48]

From June 2017 until May 2021, Moore was CEO of the Robin Hood Foundation, a charitable organization that attempts to alleviate problems caused by poverty in New York City. It works mainly through funding schools, food pantries and shelters. It also administers a disaster relief fund.[49][50][1][51] During his tenure as CEO, the organization also raised more than $650 million, including $230 million in 2020 to provide increased need for assistance during the COVID-19 pandemic.[52] Moore also sought to expand his advocacy to include America’s poor and transform the organization into a national force in the poverty fight.[53]

Prior to his election as governor, Moore was a member of the boards of directors for Under Armour and Green Thumb Industries.[54][42][55][56] In October 2022, Moore announced that he would use a blind trust to hold his assets and resign from every board position if elected governor.[57][58] In May 2023, Moore finalized his trust, making him the first governor to have one since Bob Ehrlich.[59] In May 2025, after similar conflict of interest concerns were raised about former governor Larry Hogan during his 2024 U.S. Senate campaign, Moore signed into law a bill requiring future governors to put their assets into a blind trust or sign an agreement not to participate in decisions affecting their businesses.[60]

Books

On April 27, 2010, Spiegel & Grau published his first book, The Other Wes Moore.[61] The 200-page book explores the lives of two young Baltimore boys who shared the same name and race, but largely different familial histories that leads them both down very different paths.[13][62][63] In December 2012, Moore announced that The Other Wes Moore would be developed into a feature film, with Oprah Winfrey attached as an executive producer.[64] In September 2013, Ember published his second book, Discovering Wes Moore. The book maintains the message and story set out in The Other Wes Moore, but is more accessible to young adults.[65] In April 2021, Unanimous Media announced it would adapt The Other Wes Moore into a feature film.[66] As of June 2022, a film has yet to be produced.[67]

In January 2015, Moore wrote his third book, The Work.[68] In November 2016, he wrote This Way Home, a young adult novel about Elijah, a high school basketball player, who emerges from a standoff with a local gang after they attempt to recruit him to their basketball team, and he refuses.[69] In March 2020, Moore and former Baltimore Sun education reporter Erica L. Green wrote Five Days: The Fiery Reckoning of an American City, which explores the 2015 Baltimore protests from the perspectives of eight Baltimoreans who experienced it on the front lines.[70][71]

Disputed biographical claims

In April 2022, CNN accused Moore of embellishing his childhood and where he actually grew up.[72] Shortly after the article was published, Moore created a website that attempted to rebut the allegations.[73]

On November 19, 2024, Moore was cited with a Bronze Star Medal for meritorious service in Afghanistan. Lieutenant General Michael R. Fenzel pinned the decoration on Moore on December 14. Fenzel recommended Moore for the Bronze Star in 2006 and encouraged Moore to list the award in his application for a White House fellowship. Fenzel assumed the medal would have been awarded by the time the fellows were named. In his view, Moore’s medal was awarded 20 years late.[74] Moore failed to correct journalists who referred to him as a Bronze Star recipient, and he apologized for the mistake.[75][76][77]

In December 2025, the Washington Free Beacon accused Moore of exaggerating various details of his academic and military achievements on his 2006 White House fellowship application, in which he claimed to have graduated Oxford a year and a half earlier than he had, did not submit his doctoral thesis, was working toward a doctorate at Oxford, and was a “foremost expert” on Islamic extremism who authored four articles and featured in two books on the threat of radical Islam in Latin America. A spokesperson for Moore disputed the claims made by the Free Beacon, saying that Moore had submitted his thesis and that the website would be spreading a conspiracy theory by suggesting otherwise, though his office was unable to locate the four articles Moore claimed to have contributed to.[78] Julia Paolitto, the deputy head of university communications at Oxford University, clarified to WBFF that submitting a thesis to the Bodleian Library was not a requirement to complete the university’s MLitt program, but it was a requirement to confer degrees at a ceremony, which Moore did not have.[79] When asked about the Free Beacon report by Armstrong Williams of The Baltimore Sun, Moore described the story as a distraction and declined to release his doctoral thesis, saying that he was “not going to spend a second of my time trying to dig up a paper that I wrote 20 some odd years ago because a right-wing blog post is asking me to.”[80]

Moore has repeatedly claimed that his great-grandfather, a pastor from Charleston, South Carolina, had fled the Ku Klux Klan by moving to Jamaica in 1924.[81][82][83] In February 2026, the Washington Free Beacon examined church records, which found that his grandfather was transferred to Jamaica to replace a pastor who had died.[84] Moore rejected the Free Beacon's reporting as coming from a “right-wing blog” during a CBS News town hall later that month, suggesting that the website “should ask the Ku Klux Klan” if his family story was true.[85]

Political career

Ideology

During an August 2006 interview with C-SPAN, Moore said he identified as a “registered Democrat” who is “social moderate and strong fiscal conservative”.[86] In September 2022, he reiterated his position on fiscal issues as being “fiscally responsible”.[87] During his gubernatorial campaign, he was described as center-left[88] as well as progressive.[89] He has been described as a moderate during his tenure as governor.[90][91]

Moore has cited Jared Polis, Parris Glendening, and Roy Cooper as his political role models.[92][93]

Early political involvement

Moore first expressed interest in politics in June 1996, telling a New York Times reporter that he planned to attend law school and enter politics after two years at Valley Forge.[94] Moore first expressed interest in running for governor of Maryland during an interview with The Baltimore Sun in 2006,[26] later telling The Baltimore Sun in October 2022 that he felt the idea of holding elected office only started to feel like a real possibility in 2020, when he was about to leave his job running Robin Hood.[34]

Maryland Democratic Party picnic, 2014

Moore gave a speech at the 2008 Democratic National Convention, supporting Barack Obama for president.[95][96] In 2013, he said that he had “no interest” in running for public office, instead focusing on his business and volunteer work.[97] Later that year, Attorney General Doug Gansler said that he considered choosing Moore as his running mate in the 2014 Maryland gubernatorial election, in which he ran with state delegate Jolene Ivey.[98]

In April 2015, following the 2015 Baltimore protests, Moore said that the demonstrations in Baltimore were a “long time coming”[99] and that Baltimore “must seize this moment to redress systemic problems and grow.”[100] Moore attended the funeral for Freddie Gray but left early to catch a plane to Boston for a speech he was giving on urban poverty. He later said he “felt guilty being away, but it wasn’t just that. An audience in Boston would listen to me talk about poverty, but at a historic moment in my own city’s history, I was MIA.”[101] On the eighth anniversary of Gray’s death in April 2023, Moore made a tweet calling his death a turning point for not just those who knew Gray personally, but the entire city.[102]

In February 2017, Governor Larry Hogan nominated Moore to serve on the University System of Maryland Board of Regents.[103] In October 2020, Moore was named to serve on the transition team of Baltimore mayor-elect Brandon Scott.[104] In January 2021, Speaker of the Maryland House of Delegates Adrienne A. Jones consulted with Moore to craft her “black agenda” to tackle racial inequalities in housing, health, banking, government, and private corporations.[105]

Gubernatorial campaigns

2022

In February 2021, Moore announced he was considering a run for governor of Maryland in the 2022 election.[106] He launched his campaign on June 7, 2021,[107][108] emphasizing “work, wages, and wealth”[83][109] and running on the slogan “leave no one behind”.[110][111] His running mate was Aruna Miller, a former state delegate who represented Maryland’s 15th district from 2010 to 2019.[112]

During the primary, Moore was endorsed by House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer,[113] Prince George’s County executive Angela Alsobrooks,[114] television host Oprah Winfrey,[115] and former Governor Parris Glendening.[116] He also received backing from the Maryland State Education Association[117] and VoteVets.org.[118]

On April 6, 2022, Moore filed a complaint with the Maryland State Board of Elections against the gubernatorial campaign of John King Jr., accusing “an unidentified party” of anonymously disseminating “false and disparaging information regarding Wes Moore via electronic mail and social media in an orchestrated attempt to disparage Mr. Moore and damage his candidacy.” The complaint also suggested that King “may be responsible for this smear campaign”, which the King campaign denied.[119][120] In April 2024, King’s campaign was fined $2,000 after prosecutors connected the email address to an IP address used by Joseph O’Hearn, King’s campaign manager.[121]

Moore won the Democratic primary on July 19, 2022, defeating former Democratic National Committee chairman Tom Perez and Comptroller Peter Franchot with 32.4% of the vote.[122] During the general election, Moore twice campaigned with U.S. President Joe Biden.[123][124] He also campaigned on reclaiming “patriotism” from Republicans, highlighting his service in the U.S. Army while also bringing attention to Republican nominee and state delegate Dan Cox‘s participation in the January 6 United States Capitol attack.[125][126][127] Moore defeated Cox in the general election,[4] and became Maryland’s first black governor[128] and the first veteran to be elected governor since William Donald Schaefer.[111]

In December 2022, Moore was elected to serve as finance chair of the Democratic Governors Association.[129]

2026

On September 9, 2025, Moore announced that he would run for re-election to a second term.[130]

Governor of Maryland

Moore was sworn in on January 18, 2023.[131] He took the oath of office on a Bible owned by abolitionist Frederick Douglass, as well as his grandfather’s Bible.[132][133] The morning before his inauguration, Moore participated in a wreath-laying ceremony at the Kunta Kinte–Alex Haley Memorial at the Annapolis City Dock to “acknowledge the journey” that led to him becoming the third elected black governor in U.S. history.[134][135][136] Later that night, he held a celebratory event at the Baltimore Convention Center.[137]

As governor, Moore testified for several of his administration’s bills, making him the first governor to do so since Martin O’Malley.[138] During his first term, his legislative priorities included establishing a “service year option” for high school graduates,[139] removing regulations around new housing development,[140] and supporting military families through health care benefits, tax cuts, and employment opportunities.[141][142] He has also sought to undo or revise many of his predecessor’s decisions, including the cancellation of the Baltimore Red Line,[143] the withholding of state funding for training abortion care providers,[144] and plans to expand portions of the Capital Beltway and Interstate 270 using high-occupancy toll lanes.[145] During the 2025 legislative session, Moore and leaders of the Maryland General Assembly negotiated and passed a spending plan that cut $2.5 billion in state spending and raised more than $1 billion in new taxes to close a $3.3 billion budget deficit.[146][147]

The Francis Scott Key Bridge collapse occurred during Moore’s tenure, after which he supported and signed into law legislation to provide financial assistance to workers and businesses affected by the subsequent closure of the Port of Baltimore.[148] Following the disaster, Moore has urged Congress to pass legislation that would have the federal government cover the costs of rebuilding the bridge.[149][150] In December 2024, President Joe Biden signed into law a continuing resolution bill that included a provision to fully fund the Francis Scott Key Bridge replacement.[151][152]

In July 2025, Moore was elected as the vice chair of the National Governors Association (NGA).[153] In February 2026, President Donald Trump excluded Moore and Colorado governor Jared Polis from a bipartisan dinner event for governors and their spouses,[154] after which the NGA said they would no longer meet with Trump and multiple other Democratic governors said they would skip the event.[155] In a post on Truth Social, Trump confirmed he did not invite Moore while also making multiple baseless accusations against him.[156] Moore attended a NGA business meeting at the White House after the Trump administration reversed course and extended invites to Moore and Polis.[157]

In December 2025, The Baltimore Banner reported that Moore and several members of his administration were, at times, communicating using the Google Chat platform with the “History is Off” function activated, which auto-deletes messages after 24 hours. State law requires that every unit of the state government to have policies defining which records need to be saved and which do not. In response to the Banner's findings, the Moore administration defended its use of self-deleting messages, saying that it was an “approved internal messaging feature” and “complies fully with all Maryland records laws and retention policies”, but later said that the governor’s office would work with the attorney general of Maryland to create a “uniform retention policy” across the executive branch.[158]

Personal life

at his gubernatorial inauguration, 2023

Moore met Dawn Flythe in Washington, D.C. in 2002.[159] They moved to the Riverside community in Baltimore in 2006.[160] The couple eloped in Las Vegas while he was on a brief leave from Afghanistan and were married by an Elvis impersonator.[161] Their official wedding ceremony was held on July 6, 2007.[162] They have two children, born in 2011 and 2013.[163]

In late 2008, the Moores moved from Riverside to Guilford, where they lived until Moore’s election as governor in 2022.[164] From 2015 to 2023, he attended services at the Southern Baptist Church in east Baltimore.[165] They reside in Government House, the official residence of the Maryland governor and First Family in Annapolis, Maryland.[166]

Moore holds honorary degrees from Lafayette College,[167] Skidmore College,[168] Lincoln University,[169] and the University of the Commonwealth Caribbean.[170] He is a member of the Sons of the American Revolution; his ancestor Prince Ames served in the Massachusetts Militia in the Revolutionary War.[171]

Moore is a fan of the Baltimore Ravens, Baltimore Orioles, and New York Knicks.[172]

In June 2013, a Baltimore Sun investigation alleged that Moore was improperly receiving homestead property tax credits and owed back taxes to the city of Baltimore. Moore told The Sun that he was unaware of any issues with the home’s taxes and wanted to pay what he owed immediately.[160] In October 2022, Baltimore Brew reported that Moore had not paid any water and sewage charges since March 2021, owing $21,200 to the city of Baltimore.[173] Moore settled his outstanding bills shortly after the article was published.[174]

Military decorations and badges

Moore’s decorations and medals include:[28][77][74]

Parachutist Badge Parachutist Badge |

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic |

| 217,524 | 32.4 | |

| Democratic |

| 202,175 | 30.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 141,586 | 21.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 26,594 | 4.0 | |

| Democratic |

| 25,481 | 3.8 | |

| Democratic |

| 24,882 | 3.7 | |

| Democratic |

| 13,784 | 2.1 | |

| Democratic |

| 11,880 | 1.8 | |

| Democratic |

| 4,276 | 0.6 | |

| Democratic |

| 2,978 | 0.4 | |

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | ±% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic |

| 1,293,944 | 64.53 | +21.02 | |

| Republican |

| 644,000 | 32.12 | −24.23 | |

| Libertarian |

| 30,101 | 1.50 | +0.93 | |

| Working Class |

| 17,154 | 0.86 | N/A | |

| Green |

| 14,580 | 0.73 | +0.25 | |

| Write-in | 5,444 | 0.27% | +0.19 | ||

| Total votes | 2,005,259 | 100.0 | |||

| Democratic gain from Republican | |||||

Bibliography

- The other Wes Moore : one name, two fates, New York : Spiegel & Grau, 2010. ISBN 9780385528191

- Discovering Wes Moore : My Story, New York : Ember (Random House), 2013.ISBN 9780385741682, 9780385741675, 9780375986703

- The work : searching for a life that matters, New York : Spiegel & Grau, 2015.ISBN 9780812983845

- Wes Moore; Shawn Goodman, This way home, New York : Delacorte Press, 2015.ISBN 9780385741699

- Wes Moore; Erica L Green, Five days : the fiery reckoning of an American city, New York : One World, 2020.ISBN 9780525512363

See also

Notes

- ^ Moore is the fifth black U.S. state governor, following P. B. S. Pinchback of Louisiana, Douglas Wilder of Virginia, Deval Patrick of Massachusetts and David Paterson of New York. Pinchback and Paterson were not elected, but succeeded from the lieutenant governorship.[3]

References

- ^ a b c d e McLeod, Ethan (February 8, 2021). “Wes Moore stepping down as CEO of New York’s Robin Hood Foundation”. Baltimore Business Journal. Archived from the original on February 8, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- ^ Moore, Wes. “Coming Back With Wes Moore”. PBS.org. Archived from the original on August 15, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Milevski, Laila (January 19, 2023). “How many Black governors have served in the U.S. before Wes Moore?”. Baltimore Banner. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Epstein, Reid J. (November 9, 2022). “Moore, a Democrat, Will Become Maryland’s First Black Governor”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Booker, Brakkton (November 8, 2022). “Wes Moore makes history as Maryland’s first Black governor”. Politico. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ May, Eric Charles (December 17, 1987). “PEOPLE”. The Washington Post. Retrieved July 20, 2022.

- ^ “Excerpt from The Other Wes Moore”. Oprah.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ “Joy Thomas Moore”. MAEC, Inc. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ “Wes Moore for Maryland”. Wes Moore for Maryland. Archived from the original on October 4, 1999. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- ^ “About The Author”. The Other Wes Moore. Archived from the original on July 15, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Cassie, Ron (November 9, 2022). “Wes Moore to Become Maryland’s First Black Governor”. Baltimore. Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c “Character List”. The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ a b c Moore, Wes (January 11, 2011). The Other Wes Moore. Random House Publishing Group. pp. 250. ISBN 9780385528207. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ Office of Governor Wes Moore (August 1, 2025). “Governor Wes Moore Answers the Web’s Most Searched Questions”. Retrieved August 6, 2025 – via YouTube.

- ^ “The Wes Moores: two fatherless boys, 2 different paths”. MinnPost. November 2, 2012. Archived from the original on November 3, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ Cheng, Allen (October 7, 2020). “The Other Wes Moore Book Summary, by Wes Moore”. Allen Cheng. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved December 27, 2020.

- ^ Draper, Robert (October 4, 2024). “Kamala Harris and the Influence of an Estranged Father Just Two Miles Away”. The New York Times. Retrieved October 4, 2024.

- ^ Trent, Sydney (November 2, 2022). “Wes Moore tried to run away from military school. It changed his life instead”. The Washington Post. Retrieved November 2, 2022.

- ^ a b “Johns Hopkins Student Selected for Rhodes Scholarship”. Headlines@Hopkins (Press release). Johns Hopkins University. December 10, 2000. Retrieved October 8, 2025.

- ^ “Author, JHU alum Wes Moore to speak at School of Education commencement”. April 17, 2013. Archived from the original on August 1, 2013. Retrieved October 11, 2016.

- ^ Lee, Edward (December 15, 2022). “‘The guy’s got a way about him’: Maryland Gov.-elect Wes Moore honed leadership skills as Johns Hopkins football player”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 15, 2022.

- ^ “Former JHU Football Player Wes Moore Selected as 2006-07 White House Fellow”. hopkinssports.com. Johns Hopkins Blue Jays. June 21, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ “Maryland’s New Governor, Wes Moore, Is a Brother of Alpha Phi Alpha”. watchtheyard.com. Watch The Yard. November 8, 2022. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Cadiz, Laura (December 11, 2000). “Hopkins senior a Rhodes scholar”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (January 23, 2001). “Payoff on a Parent’s Persistence”. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c Davis, Julie Hirschfeld (July 3, 2006). “Path leads city man to halls of power”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Harris, Elizabeth (April 25, 2017). “Robin Hood, Favorite Charity on Wall Street, Gets New Leader”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c Wood, Pamela (November 9, 2022). “Who is Maryland’s next governor, Wes Moore?”. Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 9, 2022.

- ^ Weisz, Zac (November 1, 2022). “Wes Moore has a plan”. National Journal. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Rogers, Keith (April 27, 2014). “Author to screen his PBS documentary on returning veterans”. Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ “The White House Announces Regional Finalists for the 2006-2007 White House Fellowships”. The White House. February 27, 2006. Archived from the original on September 5, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ “Class of 2006-2007”. White House Fellows. The White House. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved September 5, 2022.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (July 23, 2022). “What you need to know about Maryland Democratic gubernatorial nominee Wes Moore”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ^ a b Janesch, Sam (October 8, 2022). “After a lifetime of circling politics, Wes Moore picks his moment. Will Maryland voters hire him for his most ambitious job yet?”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ “40 Under 40 Class of 2009”. crainsnewyork.com. Crain’s New York Business. July 26, 2018. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Messner, Rebecca (December 11, 2012). “Back in Baltimore, Wes Moore has big plans for his hometown”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Coming Back with Wes Moore”. pbs.org. PBS. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Peterson, Tyler (August 6, 2013). “PBS Orders COMING BACK WITH WES MOORE Veterans Special”. Broadway World. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Zurawik, David (May 9, 2014). “‘Coming Back’ – At last, TV does right by veterans”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Herbst, Diane (June 29, 2017). “The Improbable Life of Wes Moore, the New CEO of The Robin Hood Foundation: ‘We Are Not Promised Anything’“. People. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Gantz, Sarah (June 15, 2015). “Wes Moore wants to help more students succeed in college”. Baltimore Business Journal. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Mirabella, Lorraine (September 3, 2020). “Wes Moore takes on director role at Under Armour”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Bowie, Liz; Wood, Pamela (May 3, 2022). “Wes Moore says his Baltimore education business was a success. The reality is much more complicated”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Zurawik, David (September 9, 2016). “‘All the Difference’ tells new story of young black men in college”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “All the Difference | POV”. pbs.org. PBS. Archived from the original on September 9, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Dunn, Susan (September 19, 2016). “Wes Moore to Host Monthly Show on WYPR”. Baltimore Fishbowl. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Future City”. www.wypr.org. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- ^ Britto, Brittany (September 19, 2016). “Wes Moore to host monthly show on WYPR starting this week”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Wes Moore | Robin Hood”. robinhood.org. Archived from the original on January 3, 2018. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ Epstein, Reid (July 16, 2022). “Unpredictable Maryland Governor’s Race Pits Old Guard vs. Upstarts”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved July 18, 2022.

- ^ CNBC profile Archived July 18, 2022, at the Wayback Machine, Robin Hood Foundation CEO Wes Moore: ‘Have faith, not fear. I feel that has guided me’, February 16, 2021

- ^ Deutch, Gabby (October 18, 2021). “Wes Moore bets on Maryland”. Jewish Insider. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Gordon, Amanda L. (January 12, 2018). “Robin Hood CEO, Tina Fey, Gerwig Start New York’s Awards Season”. Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ Neukam, Stephen (April 29, 2022). “Maryland gubernatorial candidate’s financial connections pose conflict problems”. Capital News Service. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ “Maryland Governor-elect Wes Moore Steps Down From Under Armour’s Board of Directors”. GlobeNewswire (Press release). November 11, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2022.

- ^ “Green Thumb Industries Announces Departure of Wes Moore from Board of Directors”. GlobeNewswire (Press release). March 11, 2022. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (October 28, 2022). “Dan Cox and Wes Moore won’t release their tax returns in Maryland’s gubernatorial race. Here’s what’s known about their finances”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 28, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (November 1, 2022). “Wes Moore says he’ll hand control of his investments to a blind trust if elected governor”. Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 1, 2022.

- ^ Sears, Bryan P. (May 1, 2023). “Moore puts millions into blind trust, will sell off major portion of cannabis holdings”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved May 1, 2023.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (May 6, 2025). “New ethics law clamps down on future Maryland governors’ business dealings”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved May 6, 2025.

- ^ Rosenthal, Dave (April 27, 2010). “The Other Wes Moore — the two faces of Baltimore”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ “The Other Wes Moore: One Name and Two Fates—A Story of Tragedy and Hope”. Publishers Weekly. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Sragow, Michael (April 30, 2010). “‘The Other Wes Moore’ tells a tale of two inner-city destinies”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 21, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Messner, Rebecca (December 11, 2012). “Oprah executive producing film adaptation of ‘The Other Wes Moore’“. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Moore, Wes. “Discovering Wes Moore”. Penguinrandomhouse.com. Penguin Random House. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ^ D’Allesandro, Anthony (April 27, 2021). “Unanimous Media & Pathways Alliance Arm Developing Feature Adaptation Of ‘The Other Wes Moore’“. Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on April 27, 2021. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Swift, Tim (May 31, 2022). “Oprah Winfrey, Maryland governor candidate Wes Moore to hold virtual fundraiser”. WBFF. Archived from the original on June 1, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ McCauley, Mary Carole (January 24, 2015). “Baltimore author Wes Moore publishes his second book”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Moore, Wes (November 10, 2015). This Way Home. Random House Childrens Books. p. 256. ISBN 978-0385741699.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (June 28, 2020). “Wes Moore, others discuss underlying race issues, reforms and societal failures in virtual ‘Five Days’ panel”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Greenhouse, Lisa (September 16, 2020). “A Look at Wes Moore’s new Book about the Baltimore Uprising “Five Days”“. Enoch Pratt Free Library. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Dovere, Edward-Isaac (April 13, 2022). “A rising Democratic star told his origin story. But did he allow a narrative to take hold that didn’t match the facts?”. CNN. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Stole, Bryn (April 15, 2022). “‘I’ve been very clear and transparent,’ Maryland gubernatorial candidate Wes Moore says about his Baltimore ties”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ a b Cox, Erin (December 21, 2024). “Eighteen years and one controversy later, Wes Moore gets a Bronze Star”. The Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2025.

- ^ Frost, Mikenzie (April 28, 2022). “Bronze Star recipient? Wes Moore seen failing to correct record again in past interview”. WBFF. Archived from the original on April 28, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Stole, Bryn (April 29, 2022). “Maryland’s Wes Moore pushes back against criticism he failed to set interviewers straight about his background”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on April 29, 2022. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ a b Epstein, Reid J. (August 29, 2024). “Wes Moore and the Bronze Star He Claimed but Never Received”. The New York Times. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ Kerr, Andrew (December 11, 2025). “EXCLUSIVE: Wes Moore Won a Key White House Post Claiming He Was ‘Touted as a Foremost Expert’ on Radical Islam and Was Studying for an Oxford PhD—But His Thesis Is ‘Missing’ and There’s No Evidence He Was Ever a Doctoral Student”. Washington Free Beacon. Retrieved December 12, 2025.

- ^ Frost, Mikenzie (December 12, 2025). “Gov. Moore addresses questions about academic record while at Oxford University”. WBFF. Retrieved January 7, 2025.

- ^ Williams, Armstrong (December 24, 2025). “Wes Moore on integrity, radical Islam and running for president: a conversation with The Sun”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 24, 2025.

- ^ Moore, Wes (August 19, 2017). “Opinion | The KKK chased my grandfather from the U.S., but he returned. Here’s what he’d say now”. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 12, 2026.

- ^ Wood, Marie Robey (November 1, 2020). “Wes Moore – With a Little Help From His Friends – Sees a Historic Moment”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved February 12, 2026.

- ^ a b Ball, Molly (February 14, 2023). “Where Wes Moore Comes From”. TIME. Easton, Maryland. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

- ^ Kerr, Andrew (February 4, 2026). “Wes Moore Says the KKK Chased His Great-Grandfather Out of South Carolina. Historical Records Tell a Different Story”. Washington Free Beacon. Retrieved February 10, 2026.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (February 15, 2026). “5 key moments from Gov. Wes Moore’s nationally televised town hall”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved February 15, 2026.

- ^ “Q&A with Westley Moore”. c-span.org. C-SPAN. August 25, 2006. Archived from the original on November 9, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

You know I look at my history and I look at the fact that I am, you know, I’m a social moderate. I’m a, you know, strong fiscal conservative. I’m a military officer. I’m an investment banker and I just happen to be also a registered Democrat.

- ^ Cox, Erin; Wiggins, Ovetta (September 18, 2022). “Charisma fueled Wes Moore’s primary win. Now he sharpens his focus on policy”. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Cox, Erin (September 19, 2022). “Poll: Wes Moore leads big against Dan Cox in Md. governor’s race”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Gaskill, Hannah; Janesch, Sam (July 18, 2022). “Five questions ahead of Maryland’s vacation time primary election”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 18, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Peck, Louis (July 18, 2023). “The Almanac of American Politics on Moore: A charismatic leader who broke barriers as a political outsider”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ^ Booker, Brakkton (November 8, 2022). “Wes Moore makes history as Maryland’s first Black governor”. Politico. Retrieved April 10, 2025.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (December 15, 2021). “Glendening Backs Moore in Democratic Race for Governor”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Tim; Swift, Jim (September 27, 2022). “Can Wes Moore’s Progressive Patriotism Make Him a Democratic Star?”. The Bulwark. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Rhoden, William (June 28, 1996). “ON BASKETBALL;No Longer Trapped by the Stuff Dreams Are Made Of”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 8, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2022.

- ^ Mulcahy, Conrad (August 29, 2008). “THE CAUCUS; Denver Brigade”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ “2008 Democratic Convention, Day 4”. c-span.org. C-SPAN. August 28, 2008. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ Broadwater, Luke (June 9, 2013). “What’s next for Wes Moore?”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Wagner, John (October 11, 2013). “Gansler to announce Jolene Ivey as running mate in Maryland’s race for governor”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 4, 2015. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Wes Moore: Demonstrations a long time coming”. MSNBC. April 28, 2015. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved September 18, 2015.

- ^ Marbella, Jean; Scharper, Julie (April 29, 2015). “After Baltimore riots, fighting an image that paints a city ‘with no control over itself’“. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Burg, Daniel Cotzin (August 11, 2020). “Memories of Freddie Gray and those Fiery ‘Five Days’ of Reckoning in Baltimore”. JMORE Baltimore Jewish Living. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ Sullivan, Emily; Wintrode, Brenda (April 22, 2023). “Banner political notes: Unions unite; New Montgomery delegate; Baltimore police union vs. Moore”. Baltimore Banner. Retrieved April 22, 2023.

- ^ Cox, Erin (February 17, 2017). “Baltimore author Wes Moore nominated to University System of Maryland board”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ “Mayoral candidate Brandon Scott names civic, business and community leaders to transition team”. Baltimore Fishbowl. October 20, 2020. Archived from the original on September 23, 2022. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- ^ Wiggins, Ovetta (January 19, 2021). “Maryland House speaker to unveil a ‘Black agenda’ focused on health, wealth, homeownership”. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 6, 2023.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (February 24, 2021). “Wes Moore Actively Exploring 2022 Bid for Governor”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on November 20, 2021. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Stole, Bryn (June 7, 2021). “Wes Moore, author and former nonprofit executive, launches campaign for Maryland governor”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 7, 2021. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Wiggins, Ovetta (June 7, 2021). “Author, former nonprofit leader Wes Moore launches bid for Maryland governor”. Retrieved November 20, 2021.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle (August 26, 2021). “Wes Moore: Work, Wages and Wealth Will be North Stars”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2022.

- ^ Dashniell, Timothy; Gartner, Emmett (September 16, 2022). “Cox, Moore campaigns heat up as early voting nears”. Capital News Service. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ a b Kurtz, Josh (September 6, 2022). “How Wes Moore is deploying his military service on the campaign trail”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on September 6, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (December 9, 2021). “Moore Picks Ex-Delegate Aruna Miller to Be His Running Mate”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Montellaro, Zach (April 28, 2022). “Hoyer endorses Moore in Maryland governor race”. Politico. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ Wiggins, Ovetta (March 5, 2022). “Prince George’s County Executive Alsobrooks endorses Wes Moore for Maryland governor”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ DePuyt, Bruce; Kurtz, Josh (May 31, 2022). “Political Notes: Moore Getting the Oprah Treatment, Schulz Sticks to the Script, and Gansler Lays Out Crime Plan”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on June 2, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (December 15, 2021). “Glendening Backs Moore in Democratic Race for Governor”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on April 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Gaines, Danielle E. (April 2, 2022). “Wes Moore Nabs Coveted State Teachers’ Union Endorsement”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (September 15, 2021). “Veterans’ Political Group Backs Moore for Governor”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on May 16, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2022.

- ^ Kurtz, Josh (April 6, 2022). “Moore Campaign Files Complaint, Accuses King Campaign of Circulating False Information”. Maryland Matters. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (April 6, 2022). “Anonymous accusations about Wes Moore’s Baltimore ties spark complaint in Maryland governor’s race”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on September 27, 2022. Retrieved September 27, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (April 4, 2024). “State fines former governor candidate John King $2K over anonymous Moore attacks”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved April 4, 2024.

- ^ Epstein, Reid (July 22, 2022). “Wes Moore Wins the Democratic Primary for Maryland Governor”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 23, 2022. Retrieved October 22, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (August 25, 2022). “Biden rallies Maryland Democrats and stumps for Wes Moore in Montgomery County”. Baltimore Banner. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Ford, William J. (November 7, 2022). “Joe Biden Stumps for Wes Moore in pre-Election Day rally at Bowie State University”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved November 8, 2022.

- ^ Soellner, Mica (September 9, 2022). “Wes Moore runs on patriotism to take back Maryland governor’s mansion for Democrats”. The Washington Times. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Dorman, John L. (October 29, 2022). “Maryland Democratic gubernatorial nominee Wes Moore says MAGA can’t ‘define what it means to be a patriot’“. Business Insider. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ McCammond, Alexi (December 12, 2022). “Democrats aim to steal GOP playbook on patriotism and freedom”. Axios. Retrieved December 17, 2022.

- ^ Shepard, Ryan (June 8, 2021). “Wes Moore Strives To Become The First Black Governor Of Maryland”. Black Information Network. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Montellaro, Zach (December 7, 2022). “Democrats elected a big class of young governors. They might be the future of the party”. Politico. Retrieved December 8, 2022.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (September 9, 2025). “Moore makes it official: Governor is running for reelection”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved September 9, 2025.

- ^ Cox, Erin; Wiggins, Ovetta (January 18, 2023). “Wes Moore to be sworn in, making history as Md.’s first Black governor”. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Heim, Joe (January 14, 2023). “Maryland’s governor to take oath on Frederick Douglass’s Bible”. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ Witte, Brian (January 18, 2023). “Wes Moore to Be Sworn in as Maryland’s First Black Governor”. NBC Washington. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (January 17, 2023). “Before becoming Maryland’s first Black governor, Wes Moore will visit ‘sacred place’ where enslaved people once landed”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Ford, William J. (January 18, 2023). “Moore joins with dignitaries at wreath laying ceremony before inauguration as state’s first Black governor”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (January 18, 2023). “As Wes Moore began his first day as Maryland governor, he acknowledged the state’s shameful history with slavery”. Baltimore Banner. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Kushner, Kelsey (January 18, 2023). “Wes Moore’s inaugural ball attracts thousands of supporters”. WJZ-TV. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (February 16, 2023). “Gov. Wes Moore testifies on veterans’ tax cut bill as state lawmakers begin to consider his policy priorities”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved November 8, 2023.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (February 2, 2023). “Moore’s first bills focus on poverty, improving access to banking and broadband”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Miller, Hallie (January 10, 2024). “Gov. Moore housing agenda: Development, density and renter protections”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (December 13, 2023). “Gov. Moore’s first 2024 bills would benefit military families”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Cox, Erin (January 26, 2023). “Wes Moore’s first legislation: Tax cuts and health care for veterans”. The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (June 15, 2023). “Gov. Moore relaunches planning for Red Line transit in Baltimore”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Wintrode, Brenda; Wood, Pamela (January 19, 2023). “Gov. Wes Moore releases $69 million in withheld state funds”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Lazo, Luz; Shepherd, Katie (August 21, 2023). “Maryland pursues publicly funding Beltway relief project”. The Washington Post. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Sears, Bryan P. (March 20, 2025). “Budget agreement could generate more than $1 billion in new revenue”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved January 24, 2026.

- ^ Sears, Bryan P. (May 21, 2025). “Moore signs fiscal 2026 budget with tax increases into law in final bill signing”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved January 24, 2026.

- ^ Sears, Bryan P. (April 9, 2024). “Port aid, protections for highway and election workers signed into law”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Collins, David (May 8, 2024). “Governor pushes Congress to pass Baltimore BRIDGE Relief Act”. WBAL-TV. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Borter, Gabriella (March 31, 2024). “After bridge collapse, Maryland governor urges Congress to pass funding for rebuild”. Reuters. Retrieved November 28, 2024.

- ^ Mascaro, Lisa; Amiri, Faroush (December 20, 2024). “Biden signs bill that averts government shutdown, includes Key Bridge funding”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved December 21, 2024.

- ^ Lebowitz, Megan (December 21, 2024). “Biden signs government funding bill, averting shutdown crisis”. NBC News. Retrieved December 21, 2024.

- ^ “Moore elected vice chair, chair-elect of National Governors Association”. The Daily Record. July 29, 2025. Retrieved February 8, 2026.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (February 8, 2026). “Gov. Moore says he’s been ‘singled out’ by White House, disinvited from events for governors”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved February 8, 2026.

- ^ Wood, Pamela (February 10, 2026). “Democratic governors will skip White House dinner in support of Moore”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved February 10, 2026.

- ^ Alfaro, Mariana (February 11, 2026). “Trump allows Democratic governors at White House meeting after initial snub”. The Washington Post. Retrieved February 11, 2026.

- ^ Fortinsky, Sarah (February 20, 2026). “Moore, Polis to attend governors meeting after White House reverses course”. The Hill. Retrieved February 20, 2026.

- ^ Wood, Pamela; Wintrode, Brenda (December 19, 2025). “Moore administration deleting internal messages after 24 hours”. The Baltimore Banner. Retrieved December 19, 2025.

- ^ Gruskin, Abigail (May 8, 2024). “Maryland’s first lady is trying to ‘raise amazing human beings’ in the limelight”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Calvert, Scott (June 18, 2013). “Author Wes Moore got undeserved tax breaks”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Antrim, Taylor (July 18, 2023). “Wes Moore On Gen Z, Social Media, Winning Over Republicans, and Why “Service Will Save Us”“. Vogue. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ “Dawn Flythe, Westley Moore”. New York Times. July 8, 2007. Archived from the original on June 3, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ “Being Wes Moore”. Baltimorestyle.com. June 17, 2015. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved June 2, 2022.

- ^ Janesch, Sam (July 17, 2023). “Maryland Gov. Wes Moore’s Baltimore home sells for $2.5M”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ Pitts, Jonathan (January 16, 2023). “At Gov.-elect Wes Moore’s last Baltimore church service before inauguration, hugs of encouragement, prayers of hope”. The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved January 27, 2024.

- ^ Mosbrucker, Kristen (February 22, 2023). “Gov. Wes Moore’s Baltimore City home is up for sale with $2.7M price tag”. WYPR. Retrieved February 22, 2023.

- ^ Block, Dave (May 16, 2019). “Westley Moore, Max Weinberg, and Hyman Muss ’64 to Receive Honorary Degrees”. Lafayette College (Press release). Retrieved November 8, 2025.

- ^ Campbell, Ned (February 23, 2017). “Secret’s out: Oprah to speak at Skidmore commencement”. The Daily Gazette. Retrieved January 31, 2025.

- ^ Hill, Chanel (March 10, 2025). “Lincoln names Maryland Gov. Moore as keynote speaker for graduation”. The Philadelphia Tribune. Retrieved March 11, 2025.

- ^ Davidson, Vernon (July 18, 2023). “Jamaica gives me a deep sense of clarity, says Maryland Governor Wes Moore”. Jamaica Observer. Retrieved July 23, 2023.

- ^ Pittman, Elijah; Ford, William J.; Sears, Bryan P. (August 16, 2024). “MACo Matters: Ferguson renews stance against broad-based tax increases”. Maryland Matters. Retrieved August 16, 2024.

- ^ Epstein, Reid J.; Glueck, Katie; Browning, Kellen (March 9, 2025). “Democrats Turn to Sports Radio and Podcasts to Try to Reach Young Men”. The New York Times. Retrieved March 9, 2025.

- ^ Reutter, Mark (October 5, 2022). “EXCLUSIVE: Maryland gubernatorial candidate Wes Moore owes $21,000 in delinquent Baltimore City water bills”. Baltimore Brew. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 5, 2022.

- ^ Jensen, Cassidy (October 5, 2022). “Wes Moore settled $21K in unpaid Baltimore water bills Wednesday, spokesman says”. The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on October 6, 2022. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ “Official 2022 Gubernatorial Primary Election Results for Governor / Lt. Governor”. elections.maryland.gov. Maryland State Board of Elections. July 19, 2022. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ “Official 2022 Gubernatorial General Election Results for Governor / Lt. Governor”. Maryland State Board of Elections. Retrieved December 7, 2022.

External links

- The Office of Governor Wes Moore official government website

- Wes Moore for Maryland campaign website

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Wes Moore at IMDb