News

Ukraine’s second-largest city and several strategic hubs were liberated in the operation.

A surprise counteroffensive over the weekend saw Ukrainian troops push into areas around Kharkiv in the country’s northeast, liberating villages and cities, and catching Russian troops flat-footed. The swift maneuvers threatened to encircle a portion of the Russian army and led them to rapidly abandon positions and military hardware as Ukrainian troops closed in.

The counteroffensive has recaptured around 1,160 square miles of territory since it began in earnest earlier this month, commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian Armed Forces Gen. Valerii Zaluzhnyy told the Associated Press Sunday. The eastward push caught Russian forces off-guard and forced several units to abandon their posts as Ukrainian troops took control of the strategic cities of Izyum, Balakliya, and Kupiansk — critical areas for the Russian supply and logistics lines in the Donbas region.

It’s the most significant blow to the Russian military since Ukraine pushed troops out of Kyiv in March, and frees Ukraine’s second-largest city, Kharkiv, which Russian forces have devastated with near-constant shelling for months.

Ukraine has carried out such a swift counteroffensive against Russia it’s taken even their own forces by surprise.

Ukrainian troops have recaptured huge areas of territory in the east of the country, some reportedly reaching a settlement almost on the border with Russia.

As Russian troops abandon their positions, leaving tanks, ammunition and military hardware behind, Ukrainian flags have been raised in dozens of newly liberated villages and towns.

The Conversation, – September 15, 2022

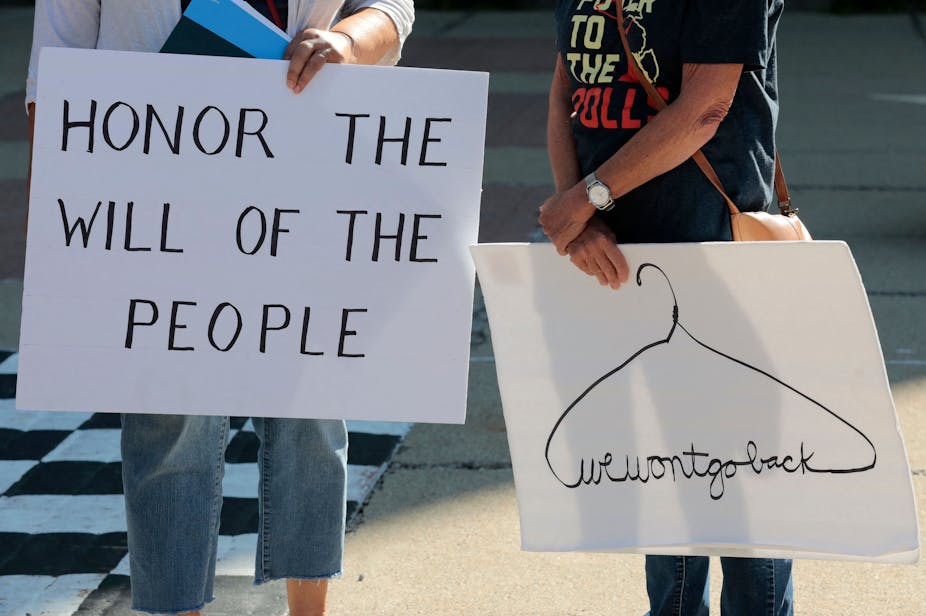

The Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade has led to a push for citizens initiatives to enshrine abortion rights. Jeff Kowalsky/AFP via Getty Images

In August 2022, a statewide referendum in Kansas saw citizens overwhelmingly reject a plan to insert anti-abortion language into the state’s constitution. It comes as a slew of similar votes on abortion rights are planned in the coming months – putting the issue directly to the people after the Supreme Court struck down the landmark Roe v. Wade ruling.

But are referendums and citizens initiatives good for democracy? It may seem like an odd question to pose on International Day for Democracy, especially at a time when many feel democracy is imperiled both in the U.S. and around the world.

As someone who researches democracy, I know the answer isn’t simple. It depends on the kind of initiative and the reason that it comes to be held.

First, some simple distinctions. Referendums and citizens initiatives are mechanisms of direct democracy – instances in which members of the public vote on issues that are commonly decided, in representative systems, by legislatures or governments. While with referendums it is typically the government that places questions on the ballot, with citizens initiatives – more common at the state level in the U.S. – the vote originates outside of government, usually through petition drives.

The Chicago Center on Democracy, which I lead at the University of Chicago, recently launched a website that tracks many of these direct democracy efforts over the past half-century.

Appealing to the masses or settling scores

That a majority of democracies retain some form of direct democracy is a testament to the legitimacy with which citizens’ voices are heard, even when, in fact, most decisions are made by our elected leaders. Often, national governments call referendums to bring important questions directly to its citizens.

But why would governments ever decide to turn a decision over to the people?

In some cases, they have no choice. Many countries, among them Australia, require that constitutional amendments be approved in popular referendums.

In other instances, such votes are optional. United Kingdom Prime Minister David Cameron, for example, was under no obligation to undertake a 2016 referendum on continued EU membership. Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos had plenty of legislative support that same year to ratify peace accords with a rebel group through an act of congress. But he turned the decision over to the people, instead.

One reason leaders voluntarily put important issues before voters is to solve disputes within their own political parties. The Brexit vote is a case in point. The U.K. Conservative Party was deeply divided over British membership in the EU, and – as Cameron later acknowledges in his memoirs – his position as head of the party, and thus as prime minister, was increasingly threatened.

In these instances, the government is in effect using the people as a referee to decide an internal dispute. It is a high-risk move, though. For Cameron, going to the country meant the end of his premiership. And six years on, the U.K. is still dealing with the fallout of that vote.

Sometimes leaders seek public support on issues about which they expect powerful opposition upon implementation. Colombia’s Santos expected resistance to the peace deal from opponents, including wealthy landed interests. He used the people as a kind of force field to protect the policy. But again, the strategy backfired. The Colombian accords were defeated, and have since faced powerful resistance when subsequent attempts were made to implement them through legislative approval.

But do these two high-profile instances illustrate fatal flaws in referendums, and direct democracy in general? Perhaps not.

Though plenty of disinformation circulated before both votes, the results probably fairly accurately reflected the people’s preferences. Moreover, they illustrate the perils to political leaders of placing issues of crucial importance before voters – they can’t be sure they will like the results.

And when their referendums fail, they may set back causes that these politicians care about. For example, Brazil held a referendum on gun control in 2005. It failed, and later pro-guns rights president Jair Bolsonaro used its failure to try to loosen restrictions on firearms, claiming that the failure of the referendum allowed him to do so.

Tool of demagogues

Sometimes the prime minister or president does prevail. A kind of referendum was used in Australia in 2017 to pressure the legislature into legalizing same-sex marriage. Conservative politicians were willing to hold a vote, with the same kind of “referee logic” as in Brexit – they were opposed to same-sex marriage, but preferred to go along with the public’s will, rather than continue to fight over this internally divisive issue.

In the end, the pro-marriage equality prime minister opted for a “postal survey” rather than a formal referendum. And the gamble worked for Australia’s leader – a very large majority expressed support of same-sex marriage and the prime minister got his way.

For every Colombia-style debacle, in which a leader holds an optional referendum but fails, one can point to governments putting matters to a popular vote to produce a force field, and winning. The approval of the public can make policy immune to –- or at least undermine – later opposition. Such was the case of same-sex marriage in Ireland, passed by referendum in 2015. The following year, Ireland settled the issue of abortion access, overturning a ban by a two-thirds majority.

Referendums are not only used by democratic leaders but also by autocrats and demagogues. Russian president Vladimir Putin put a series of constitutional reforms before voters in 2020, including one that overturned Putin’s prior term limit in office.

Accusations of fraud and intimidation followed the vote. The process could hardly have been more at odds with direct democracy and the autonomous expression of the people’s will.

Getting policy to line up with people’s will

There are no national referendums in the U.S. But American voters have a great deal of experience with initiatives at the state level – and with state-wide referendums, as well. These votes have the potential to force governments to abide by the people’s will in cases where legislators may be resisting popular policies.

Yet problems can arise with these exercises in direct democracy. Even though they are presumably citizens’ initiatives, the influence of political parties, special interests, lobbyists and big money can turn them into something quite different, as was the experience of California in the 1990s – which in turn undermined the public’s satisfaction in the initiative process.

But recently we have seen a spate of state initiatives that seem more promising – where majorities of citizens are demanding that their state legislatures bring policy more in line with public opinion. Florida voters approved ex-felon voting; Arizona voters approved bigger budgets for public schools; Missouri voters forced a reluctant legislature to expand Medicare in their state. All of these initiatives were backed with popular public support.

Most recently, Kansans said “no,” in referendum, to inserting pro-life language into their state´s constitution.

‘Let the people decide!’

The potential for mechanisms of direct democracy to improve citizen representation depends on the context in which they are held, including the manner in which they are placed on the ballot and the motives of those who placed them there.

At one extreme are autocrats like Vladimir Putin who held votes that augment his power and the length of his term. At the other are citizens frustrated by legislators whose actions stray far from public opinion. In between are measures sponsored by governments that may want to insulate policies they care about with the help of the people’s backing, and parties that throw their hands up, in the context of internal divisions, and say, “let the people decide.”

PBS NewsHour – September 17, 2022 (03:08)

In our news wrap Saturday, the Justice Department asked a federal appeals court to restore its access to the classified materials found at Mar-a-Lago while an independent arbiter conducts his review, Puerto Rico is under a hurricane warning as Tropical Storm Fiona approaches, violent protests have broken out in Haiti’s capital, and Queen Elizabeth II lies in state for a final two days in London.

Capehart and Gerson on how immigration debate and abortion access will play into midterms

Washington Post associate editor Jonathan Capehart and Washington Post opinion columnist Michael Gerson join Judy Woodruff to discuss the week in politics, including controversies over immigration and how access to abortion is likely to play into the midterm elections.

PBS NewsHour – September 14, 2022 (09:17)

Historical trends and months of polling previously predicted that Democrats will face trouble in the midterms. But recent data shows that a red wave may not be the tsunami that Republicans were hoping for. Democratic strategist Joel Benenson and Republican pollster Neil Newhouse join Amna Nawaz to discuss what they’re watching ahead of Election Day.

The Conversation, September 14, 2022 – 10:00 am (ET)

https://theconversation.com/should-you-vote-early-in-the-2022-midterm-elections-3-essential-reads-190187

New Hampshire, Delaware, and Rhode Island picked their candidates.

Winner: National Democrats

National Democrats pushed weak Republican candidates over the finish line both in a congressional race and in the New Hampshire GOP Senate primary. Don Bolduc — a retired Army brigadier general who believes Donald Trump won the 2020 election, said that the election was rigged in New Hampshire, and has made false claims about Covid vaccines — pulled off a victory over state senate president Chuck Morse in a split field. Morse conceded early Wednesday

Loser: Kevin McCarthy

The Congressional Leadership Fund (CLF), a super PAC aligned with the House minority leader, spent $1.8 million in New Hampshire’s First Congressional District to boost Matt Mowers, a veteran political operative who had been the GOP nominee in that swing district in 2020. Mowers lost. Instead, Karoline Leavitt, a 25-year-old who would be the youngest female member of Congress in history, won. Leavitt has recently refused to say whether she’d vote for McCarthy for speaker and made false claims about the 2020 election.

Winner: Elise Stefanik

Leavitt’s win wasn’t bad news for everyone in House leadership. Elise Stefanik, the House GOP conference chair, had vigorously backed Leavitt, her former staffer.

Winner: Incumbent governors

Outside of New Hampshire, Rhode Island Gov. Dan McKee managed to narrowly win the Democratic primary against a split field that included Secretary of State Nellie Gorbea and former CVS CEO Helena Foulkes.

The Conversation, – September 13, 2022

As political campaigning for the midterm elections is ramping up, millions of voters are considering how they should cast their ballots on Nov. 8, 2022. In addition to the traditional way of voting at their local precinct on Election Day, many have the option to vote earlier by mail.

With the exception of Alabama, Connecticut, Mississippi and New Hampshire, early voting is allowed in 46 states and is offered in different forms such as drop boxes, mail or early voting in person.

It’s important to check with your state’s election office, because different states have different deadlines and options available.

In Montana, for instance, early voting is allowed for about four weeks between Oct. 11 and Nov. 7. But in Texas, the early-voting period is only the 10 weekdays between Oct. 24 and Nov. 4.

1. The long, long history of early voting

Early voting periods are as old as presidential elections in the U.S.

The first presidential election occurred in 1789 and started on Dec. 15, 1788. It ended almost a month later, on Jan. 10, 1789, with the election of George Washington.

It wasn’t until 1845 that Congress adopted the Tuesday after the first Monday in November as the national Election Day.

Given the long history, Terri Bimes, an associate teaching professor of political science at the University of California, Berkeley, raises an interesting point on the impact of early voting on turnout.

“While some scholars contend that early in-person voting periods potentially can decrease voter turnout,” Bimes writes, “studies that focus on vote-by-mail, a form of early voting, generally show an increase in voter turnout.”

Regardless of overall turnout, more and more voters are choosing nontraditional ways of casting their ballots. In the 2020 election, for instance, 69% of voters nationwide voted by mail or through another means earlier than Election Day. That number was 40% in 2016.

Read more: There’s nothing unusual about early voting – it’s been done since the founding of the republic

2. Is early voting safe?

Election fraud is rare.

And mail-in ballot fraud is even rarer.

The conservative Heritage Foundation conducted a survey in 2020 and found 1,200 “proven instances of voter fraud” since 2000, with 1,100 criminal convictions over those two decades.

Only 204 allegations, and 143 convictions, involved mail-in ballots – even with more than 250 million mail-in ballots cast since 2000.

Edie Goldenberg is a University of Michigan political scientist who belongs to a National Academy of Public Administration working group that offered recommendations to ensure voter participation and public confidence during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Goldenberg writes: “The evidence we reviewed finds that voting by mail is rarely subject to fraud, does not give an advantage to one political party over another and can in fact inspire public confidence in the voting process, if done properly.”

Read more: What’s the best way to get out the vote in a pandemic?

3. Voting turnout is key to democracy

More people voted in the 2020 presidential election than in any election in the past 120 years, even as nearly one-third of eligible voters sat it out. That means nearly 80 million Americans did not vote.

Among the reasons nonvoters gave were not being registered, not being interested or not believing their vote made a difference. Despite such apathy, about 155 million voters – that’s 67% of Americans over 18 – did vote in 2020.

Part of the problem of reducing the percentage of nonvoters at the street level can be getting people to answer their doors to strangers or answering a telephone call placed by a campaign volunteer from an unrecognized number. Before the pandemic, an effective door-to-door campaign could increase turnout by almost 10%; a well-run phone campaign could add an additional 5%.

When University of California, Berkeley’s Vice Provost for Graduate Studies Lisa García Bedolla began studying voter mobilization in 2005, it was common for door-to-door campaigns to reach half of the people they tried to contact. By 2018, that number had dropped to about 18%.

To close the gap, campaigns moved toward asking people to contact people they knew and help turn out those supporters and social networks. Text messages, especially reminder texts, became the virtual door knock.

“These friend-to-friend approaches are seen as a way to cut through the noise,” Bedolla writes.

These personal approaches can also create a sense of accountability.

Knowing that someone is paying attention to your vote, however it is cast, might make a difference in a local, state or federal election.

Over the past two years, Republicans have used their dominant hold on most state legislatures to advance a polarizing agenda moving social policy sharply to the right on issues from abortion and voting to book bans and classroom teaching of race and gender.

Now, a new analysis has found that over the next decade, Democrats will face an uphill challenge to dislodge the GOP state house advantage that has allowed conservatives to advance this agenda so broadly and so quickly. In the battle for control of state legislatures, “Democrats face a defensive outlook over the decade ahead,” the Democratic group Forward Majority concludes in a report released Monday. “Good years for Democrats are ones in which power will come down to razor-thin margins; in contrast, good years for Republicans will be total routs.”

The study is based on an exhaustive effort by the group to model how the electoral competition between the two parties will evolve through 2030.

The final piece of the 2022 Senate puzzle is about to be set.

Democratic Sen. Maggie Hassan’s reelection campaign could be one of November’s most competitive races — but that depends on who wins Tuesday’s Republican primary in New Hampshire, the last nominating contest left in the battle to swing the 50-50 Senate.

The GOP’s establishment wing has lined up behind state Senate President Chuck Morse, who is mounting a late charge for the nomination against longtime polling leader Don Bolduc. But a leading Democratic super PAC has been attacking Morse on the airwaves, the latest example of the party’s involvement in GOP primaries.

New Hampshire Republicans are also picking two candidates to challenge each of the state’s vulnerable Democratic House incumbents. And just down I-95, Democrats in Rhode Island will decide whether to keep their appointed governor, Dan McKee, who took over in Providence after Gina Raimondo resigned to become President Joe Biden’s commerce secretary.

Not counting Louisiana, which runs its “jungle primaries” on November’s Election Day, Tuesday marks the final primaries of 2022. Here’s what to watch for:

NPR’s Tamara Keith and Amy Walter of the Cook Political Report with Amy Walter join Judy Woodruff to discuss the latest political news, including what’s next for Republicans and Democrats as primary season comes to a close and they turn their midterm messaging toward the general election.

Google searches for “college rankings” spike each year in the months that follow the release of US News & World Report’s annual lists of Best Colleges. The company says that about 40 million people read those lists last year; that’s more than 10 times the number of graduating high school seniors in the United States.

The company released its 2022-23 lists on Monday.

Demand for information is evident, as higher education – once affordable and accessible – has continued to become more competitive and more expensive.

In the nearly four decades since the US News rankings launched in 1983, the cost of college has ballooned more than five times for those attending four-year private institutions. The average student graduates with about $30,000 in debt for the past decade, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, which works out to more than half of their average starting salary.