Summary

Current Position: US Representative of MT-01 since 2023

Affiliation: Republican

Former Positions: United States secretary of the interior under president Donald Trump 2017 to 2019

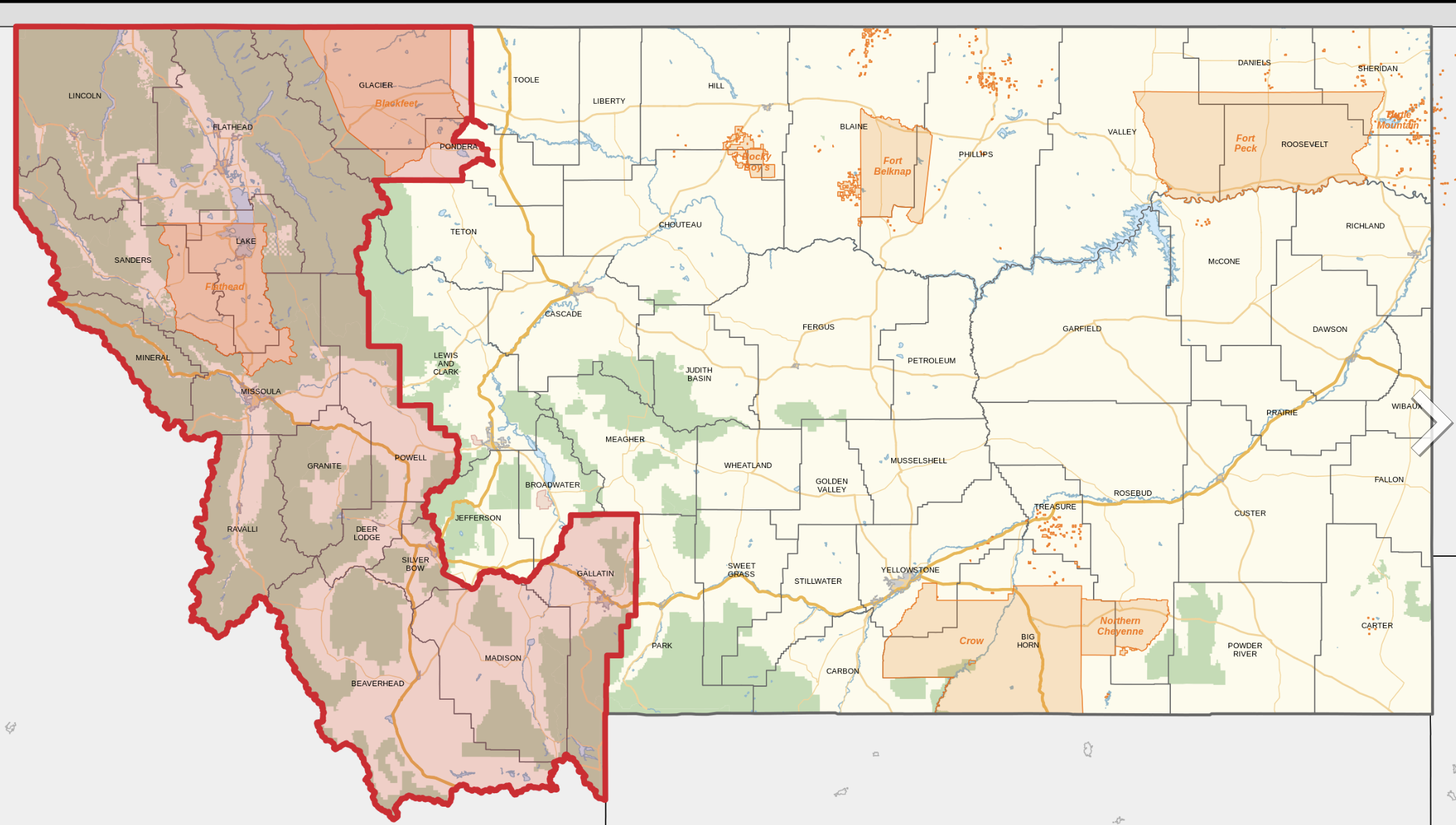

District: western third of the state

Upcoming Election:

Zinke served in the Montana Senate from 2009 to 2013 and as the U.S. representative for the at-large congressional district from 2015 to 2017. He served as the United States secretary of the interior under president Donald Trump from 2017 until his resignation in 2019 following a series of ethical scandals.

Zinke graduated from multiple colleges before he was a U.S. Navy SEAL from 1986 until 2008, retiring as a commander. In 2005, Zinke formed Continental Divide International, a property management and business development consulting company. His family members are officers of the company. In 2009, Zinke formed the consulting company On Point Montana.

OnAir Post: Ryan Zinke MT-01

News

About

Source: Government page

Ryan Zinke is a fifth generation Montanan who serves as Representative for Montana’s First Congressional District covering 16 counties in western Montana including the cities of Bozeman, Butte, Missoula, Kalispell. First elected to Congress in 2014, and serving as U.S. Secretary of the Interior between noncontiguous terms, Zinke has built a track record of accomplishments in energy, conservation, tribal and military issues. Now in his third term, Zinke is a member of the House Committee on Appropriations, focusing his legislative agenda on restoring accountability to federal spending, restoring American energy dominance, and bolstering national security at our borders and beyond.

Ryan began public service in 1985 when he joined the U.S. Navy and graduated from Officer Candidate School. He was recruited to join the U.S. Navy SEALs where he went on dozens of deployments targeting terrorist cells in Asia, war criminals in Bosnia, and combatting the rise of radical Islamic terrorists in the middle east. During his military career he held a number of leadership positions including as Ground Forces and Task Force commander at SEAL Teams SIX oversaw the U.S. Navy SEAL BUD/S training after 9/11, and was Deputy/Acting Commander of Joint Special Forces during the Iraq war. In 2006 he was awarded the Bronze Star for his service. Commander Zinke retired from active duty in 2008 after serving for 23 years.

Following his military service, Ryan was elected to the Montana State Senate and was twice elected as Montana’s sole member of the U.S. House of Representatives. During his first two terms as Congressman, Zinke served on the House Armed Services Committee and Natural Resources Committee. As a leading member of the Natural Resources Committee, Ryan challenged the Obama Administration on their policies that locked Montanans out of public lands and introduced legislation to strengthen public access and conservation.

In December 2016, Congressman Zinke was nominated to be the United States Secretary of the Interior by President Donald J. Trump and later confirmed by a bipartisan vote in the Senate.

Ryan is a fifth generation Montanan who was born in Bozeman and lives on the same property in Whitefish his family has called home since the 1950s. In high school, Ryan served as class president and was a multiple sport, All-State athlete who earned a place in the Whitefish High School Football Hall of Fame. He received an athletic scholarship to the University of Oregon where he lettered all four years and graduated with a B.S. in Geology. He also holds a Masters in Business Finance from National University and a Masters in Global Leadership from the University of San Diego.

Ryan is married to the former Lolita Hand and together they have three children: two sons, Wolfgang and Konrad, a daughter Jennifer. Ryan and Lola are grandparents to two granddaughters.

Personal

Full Name: Ryan K. Zinke

Gender: Male

Family: Wife: Lolita; 3 Children: Jennifer, Wolfgang, Konrad

Birth Date: 11/01/1961

Birth Place: Bozeman, MT

Home City: Whitefish, MT

Religion: Lutheran

Source: Vote Smart

Education

MS, Global Leadership, University of San Diego, 2004, Grade Point Average of 4.0

MBA, Finance, National University, 1991, Grade Point Average of 4.0

BS, Geology, University of Oregon, 1984, Grade Point Average of 3.4

Political Experience

Representative, United States House of Representatives, Montana, District 1, 2023-present

Candidate, United States House of Representatives, Montana, District 1, 2022

Secretary, United States Department of the Interior, 2017-2019

Representative, United States House of Representatives, District At-Large, 2014-2017

Nominated by President-elect Donald Trump, Secretary of the Interior, United States of America, December 13, 2016

Candidate, Montana State Lieutenant Governor, 2012

Senator, Montana State Senate, District 2, 2008-2012

Professional Experience

Chief Executive Officer, Continental Divide International, 2008-present

President, Continental Divide International, 2008-2014

Mission Commander, SEAL Team Six, United States Navy, 1985-2008

Director, Naval Special Warfare Technology, 2006

Deputy Commander, CJSOTF-AP Special Forces, Iraq, 2004

Commander, Joint Task Force, Kosovo, 2001

Commander, Joint Task Force, Bosnia, 1999

Ground Force Commander, Joint Special Operations Command, 1996

Offices

Washington DC Office

512 Cannon House Office Building

Washington, DC 20515

Phone: (202) 225-5628

Missoula District Office

2901 W. Broadway Street

Suite 200

Missoula, MT 59808

Phone: (406) 317-0276

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Election Results

To learn more, go to this wikipedia section in this post.

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

Appropriations:

The subcommittee on Interior, Environment and Related Agencies.

The subcommittee on Military Construction, Veterans Affairs and Related Agencies.

The subcommittee on Transportation, Housing and Urban Development and Related Agencies.

U.S. Joint Commission on China

Science, Space, and Technology:

The subcommittee on the Environment.

Caucuses:

Northern Border Security Caucus (Co-Chair).

Western Caucus.

Native American Caucus.

Republican Study Committee.

New Legislation

Learn more about legislation sponsored and co-sponsored by Congressman Zinke.

Issues

Source: Government page

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

District

Source: Wikipedia

Montana’s 1st congressional district is a congressional district in the United States House of Representatives that was apportioned after the 2020 United States census. The first candidates ran in the 2022 elections for a seat in the 118th United States Congress.

Montana’s 1st congressional district is a congressional district in the United States House of Representatives that was apportioned after the 2020 United States census. The first candidates ran in the 2022 elections for a seat in the 118th United States Congress.

This seat’s current representative is Republican Ryan Zinke.

Wikipedia

Contents

(Top)

1

Early life and education

2

Military career

3

Business ventures

4

Political career

5

Secretary of the Interior (2017–2019)

6

Return to U.S. House of Representatives (2023–present)

7

Personal life

8

Awards and decorations

9

Electoral history

10

See also

11

References

12

External links

Ryan Keith Zinke (/ˈzɪŋki/ ZING-kee; born November 1, 1961) is an American politician and businessman serving as the U.S. representative for Montana’s 1st congressional district since 2023. A member of the Republican Party, Zinke served in the Montana Senate from 2009 to 2013 and as the U.S. representative for the at-large congressional district from 2015 to 2017.[1] He served as the United States secretary of the interior under president Donald Trump from 2017 until his resignation in 2019 following a series of ethics inquiries.[2]

Zinke graduated from college before serving as a U.S. Navy SEAL from 1986 until 2008, retiring as a commander.[3] The first SEAL to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives,[4] he formerly served as a member of the Natural Resources Committee and the Armed Services Committee.[5] As a member of Congress, Zinke supported the use of ground troops in the Middle East to combat ISIS, and opposed the Affordable Care Act, various environmental regulations, and the transfer of federal lands to individual states.

Zinke was appointed secretary of the interior by Trump. He was confirmed on March 1, 2017, becoming the first SEAL and the first Montanan since statehood to occupy a Cabinet position.[6][7]

As Secretary, Zinke opened some federal lands for oil, gas and mineral exploration and extraction.[8] His actions as interior secretary raised ethical questions and were investigated by the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General.[9][10] In October 2018, the Interior’s inspector general referred the investigation to the Department of Justice.[11][12] On December 15, 2018, Trump announced that Zinke would leave his post as of January 2, 2019,[13][14] to be replaced by his deputy, David Bernhardt.[15] The Inspector General’s report concluded that Zinke had repeatedly violated ethical rules and then lied to investigators.[16][17]

On March 2, 2026, Zinke announced he would not seek re-election in 2026.

Early life and education

Zinke was born in Bozeman, Montana, and raised in Whitefish. He is the son of Jean Montana Harlow Petersen and Ray Dale Zinke, a plumber.[18][19] He was an Eagle Scout.[20] He was a star athlete at Whitefish High School and accepted a football scholarship to the University of Oregon in Eugene; recruited as an outside linebacker, he switched to offense and was an undersized starting center for the Oregon Ducks in the Pac-10 under head coach Rich Brooks.[21][22] Zinke earned a bachelor of science degree in geology in 1984 and graduated with honors.[23][24] He intended to pursue a career in underwater geology.[24] Despite never working as a geologist, Zinke publicly calls himself a geologist.[24][25] He earned a master’s degree in business administration from National University in 1993 and a Master of Science degree in global leadership from the University of San Diego in 2003.[23]

Military career

Zinke served as a U.S. Navy SEAL from 1986 to 2008, retiring at the rank of commander.[26] He graduated from Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training (BUD/S) class 136 in February 1986[3] and subsequently served with SEAL Team ONE. Following SEAL Tactical Training and completion of a six-month probationary period, he received the 1130 designator as a Naval Special Warfare Officer, entitled to wear the Special Warfare insignia also known as “SEAL Trident”. Zinke was assigned as a First Phase Officer of BUD/S from 1988 to 1991. In 1991, he received orders to United States Naval Special Warfare Development Group (NSWDG) and completed a specialized selection and training course. Zinke served at the command until 1993, during which time he planned, rehearsed, and took part in carrying out classified operations.[21][27] He then served as a Plans officer for Commander in Chief, U.S. Naval Forces, Europe and served a second tour with NSWDG as team leader, ground force commander, task force commander and current operations officer from 1996 to 1999.[21]

In the late 1990s, Zinke paid back the Navy $211 after improperly billing the government for personal travel expenses. His former commanding officer, retired vice admiral Albert M. Calland III, said that as a result, Zinke received a June 1999 Fitness Report that blocked him from being promoted to a commanding officer position or to the rank of captain.[28][29] Zinke acknowledged the error but maintains that the incident did not adversely affect his career.[28] His promotion from lieutenant commander to commander was approved the next year.[30]

From 1999 to 2001, Zinke served as executive officer for Naval Special Warfare Unit Two and then as executive officer, Naval Special Warfare Center from 2001 to 2004. In 2004, Zinke was the deputy and acting commander of the Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force-Arabian Peninsula.[23] His campaign website stated that he was “the deputy and acting commander” of Combined Joint Special Operations Task Force–Arabian Peninsula and “led a force of more than 3,500 Special Operations personnel in Iraq” in 2004.[28] Retired Major General Michael S. Repass, who was Zinke’s superior in Iraq, told The New York Times that these claims “might be a stretch” but that Zinke “did a good job” and was “a competent guy”.[28] After his tours in Iraq, Zinke served “as the second-ranking officer (and briefly acting commander) of the main SEAL training center.”[28] In 2006, he was selected to establish the Naval Special Warfare Advanced Training Command, serving as dean of the graduate school until his retirement from active duty in 2008.[23] The graduate school had 250 educators, offering over 43 college-level courses to over 2,500 students annually at 15 different locations worldwide.[31] Zinke retired from the Navy in 2008.[28][29]

Business ventures

In 2005, Zinke formed Continental Divide International, a property management and business development consulting company. His family members are officers of the company. In 2009, Zinke formed the consulting company On Point Montana. He served on the board of the oil pipeline company QS Energy (formerly Save the World Air) from 2012 to 2015. In November 2014, Zinke announced that he would pass Continental Divide to his family while remaining in an advisory role.[32]

In January 2019, Zinke began a new job as the managing director of Artillery One, a cryptocurrency investment firm founded by investor Daniel Cannon, saying that he was “going to make Artillery One great again.”[33] In an interview, he said:

“I’m focused on cybersecurity, protection of infrastructure and emerging countries that can act as a test bed for new technologies. There is some suspicion that blockchain does not really work. We think it does and we want to showcase the utility and flexibility of the model.”[34]

The company is working on a test bed project in Kosovo, where Zinke served during his time in the U.S. Navy.[34] Zinke also took consulting jobs with several energy firms.[35]

Political career

Montana Senate (2009–2013)

Zinke was elected to the Montana Senate in 2008, serving from 2009 to 2013, representing the city of Whitefish. While serving in the State Senate, he “was widely seen as a moderate Republican” but drifted to the right.[36] Zinke was selected as chair of the Senate Education Committee and promoted technology in the classroom, rural access to education and local control over schools.[37] He also served on the Senate Finance and Claims Committee.[38] As a state senator, Zinke was also a member of the SEMA-supported State Automotive Enthusiast and Leadership Caucus, a bipartisan group of state lawmakers sharing an appreciation for automobiles.[39][40]

In 2008, Zinke said he “support[s] increased coal production for electrical generation and believe[s] it can and should be done with adequate environmental safeguards” and that he “believe[s] the use of alternate energy sources and clean coal is preferred over petroleum based fuels”.[41] In 2010, he signed a letter calling global warming “a threat multiplier for instability in the most volatile regions of the world” and saying that “the clean energy and climate challenge is America’s new space race”. The letter spoke of “catastrophic” costs and “unprecedented economic consequences” that would result from failing to act on climate change and asked President Barack Obama and Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi to champion sweeping clean energy and climate legislation.[42]

In 2013, Zinke hosted a radio show in which he engaged with and promoted fringe conspiratorial views, including birtherism (the contention that Obama was not born in the United States). Zinke said on the show that he was not sure whether Obama was a foreign citizen and called on Obama to release his college transcripts. Later, in 2016, as a congressman, Zinke appeared on the radio show Where’s Obama’s Birth Certificate, known for its promotion of birther conspiracy theories.[43]

Elections

2012 campaign for lieutenant governor

Zinke was the running mate of Montana gubernatorial candidate Neil Livingstone in the 2012 election.[44] The Livingstone/Zinke ticket won 8.8% of the vote, a total of 12,038 votes, and finished fifth out of seven in the Republican primary.[45] The eventual nominees, Rick Hill and Jon Sonju, lost the general election to the Democratic nominees, Attorney General Steve Bullock and Montana National Guardsman John Walsh.

In 2012, Zinke founded a super PAC named Special Operations for America, or SOFA, to support Mitt Romney‘s 2012 presidential campaign. It raised over $100,000[46] and paid $28,258 to Continental Divide International, Zinke’s company, for fundraising consulting.[47] Zinke appointed right-wing commentator Paul E. Vallely, a promoter of “birther” claims and other anti-Obama conspiracy theories, to SOFA’s board.[48] Zinke announced he was resigning as chairman of SOFA on September 30, 2013, with his friend former Navy SEAL Gary Stubblefield taking his place.[46] While Zinke’s financial disclosure report for 2014 listed him as chairman of SOFA, SOFA had been making independent expenditures in support of Zinke’s campaign since November 20, 2013.[47] In 2014, the Campaign Legal Center and Democracy 21 filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission regarding coordination between Zinke’s campaign and SOFA. As of December 2016, the FEC had taken no action on the matter.[47]

2014 House election

In the spring of 2014, Zinke announced his candidacy for Montana‘s at-large congressional district, a seat vacated when the incumbent, Steve Daines, successfully sought a seat in the U.S. Senate.[49]

During the Republican primary, Zinke attracted attention for calling Hillary Rodham Clinton “the real enemy” and the “anti-Christ.”[36][50] He touted his anti-abortion credentials and was endorsed by the Montana Right to Life Association.[51]

Zinke won the five-way Republican primary with 43,766 votes (33.25%) and defeated Libertarian perennial candidate Mike Fellows and Democratic nominee John Lewis, a former state director for U.S. Senator Max Baucus, in the general election, with 55.4% of the nearly 350,000 votes cast statewide.[52]

2016 House election

In 2016, Zinke ran unopposed in the Republican primary on June 7 and faced the Democratic nominee, Superintendent of Public Instruction Denise Juneau in the general election on November 8.[53] He defeated Juneau with 56% of the vote.[54]

U.S. House of Representatives (2015–2017)

In Congress, Zinke supported the deployment of U.S. ground troops to combat ISIS, “abandoning” the Affordable Care Act, and cutting regulations.[36] He supported a Republican effort to repeal the estate tax.[55][56]

Zinke condemned the “anti-Semitic views” held by neo-Nazis planning a march in support of Richard B. Spencer in Whitefish, Montana, in January 2017.[57]

Political positions

Education

In 2015, Zinke voted for an amendment proposed by Representative Dave Loebsack that provided for the expansion of the use of digital learning through the establishment of a competitive grant program to implement and evaluate the results of technology-based learning practices.[58] The amendment passed, 218–213,[59] but stalled and died in the Senate.

Environmental regulation

Zinke frequently voted in opposition to environmentalists on issues including coal extraction and oil and gas drilling.[60] When Trump opened nearly all U.S. coastal waters to extractive drilling, rescinding Obama’s restrictions a dozen coastal states out of 30 total protested. Zinke visited with Florida governor Ron DeSantis and exempted only Florida’s coast from drilling.[61][62]

Climate change

Zinke has shifted over time on the issue of climate change.[63] In 2010, while in the Montana Senate, Zinke was one of nearly 1,200 state legislators who signed a letter to President Barack Obama and Congress calling for “comprehensive clean energy jobs and climate change legislation.”[63] Since 2010, however, he has repeatedly expressed doubt about anthropogenic climate change; in an October 2014 debate, Zinke said, “it’s not a hoax, but it’s not proven science either.”[63] During Senate confirmation hearings on his nomination as Interior Secretary, Zinke said that humans “influence” climate change, but did not acknowledge the scientific consensus that human activity is the dominant cause of climate change.[64]

Transfers of federal lands to states

Zinke broke with most Republicans on the issue of transfers of federal lands to the states, calling such proposals “extreme” and voting against them.[65] In July 2016, he withdrew as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in protest of the portion of the party’s draft platform that would require that certain public lands be transferred to state control. Zinke said he endorsed “better management of federal land” rather than transfers.[66]

Final committee assignments, 2017

Source:[67]

Caucus memberships

Secretary of the Interior (2017–2019)

Zinke was named as President-elect Donald Trump‘s nominee for United States Secretary of the Interior on December 13, 2016, at the recommendation of Trump’s son, Donald Trump Jr.[69][70] The Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee approved his nomination by a 16–6 vote on January 31, 2017,[71] and he was confirmed by the full Senate by a 68–31 vote on March 1.[7][72] Zinke had the support of both of Montana’s senators, including Democrat Jon Tester.[73] Zinke was sworn into office by Vice President Mike Pence the same day.[74]

The day after his swearing-in, Zinke rode a United States Park Police horse named Tonto several blocks to the entrance of the Department of Interior’s Main Interior Building to his official welcoming ceremony.[75][76]

On May 24, 2017, in the Montana special election to fill Zinke’s vacated House seat, Republican nominee Greg Gianforte defeated Democratic nominee Rob Quist, with 49.7% of the vote to Quist’s 44.1%.[77]

Rescinded ban on lead bullets

On his first full day in office, Zinke rescinded the policy implemented by outgoing Fish and Wildlife Service Director Daniel M. Ashe on January 19, 2017, the last day of the Obama administration, that banned the use of lead bullets and lead fishing tackle in national wildlife refuges. Zinke said in a statement:

“Over the past eight years … hunting, and recreation enthusiasts have seen trails closed and dramatic decreases in access to public lands across the board. It worries me to think about hunting and fishing becoming activities for the land-owning elite. This package of secretarial orders will expand access for outdoor enthusiasts and also make sure the community’s voice is heard.”[78]

The regulation was meant to help prevent lead contamination of plants and animals.[79][80][81]

The move was opposed by the Sierra Club,[79] Center for Biological Diversity,[82] and other environmental groups.[81][82] The rollback was praised, however, by Senator Steve Daines,[79] the National Rifle Association of America,[79][80] and National Shooting Sports Foundation,[82] as well as other “gun rights advocates, sportsmen’s groups, conservatives and state wildlife agencies.”[79]

National Monument reductions

In April 2017, Zinke began reviewing at least 27 national monuments to determine whether any of them could be reduced in size. In June 2017, he recommended that Bears Ears National Monument‘s boundaries be scaled back. In August, he added the Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument and Cascade-Siskiyou National Monument to the list of monuments to be shrunk, while also calling for new management rules for multiple national monuments to decrease the number of actions that are prohibited within the monuments.[83][84][85]

In December 2017, Trump signed executive proclamations that reduced Bears Ears National Monument by 85% and Grand Staircase–Escalante National Monument by almost 46%. These moves prompted several legal challenges. A day later, Zinke issued a report recommending that Trump also shrink two more national monuments—Gold Butte National Monument in Nevada and Cascade–Siskiyou National Monument in Oregon. He also recommended changes to the management of six other national monuments.[86] These changes were welcomed by Republicans such as Representative Rob Bishop, the chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, but condemned by Democrats and environmentalist groups such as the Natural Resources Defense Council and Sierra Club.[86][87]

After The New York Times took Zinke’s Interior Department to court, it won and got 25,000 documents, of which 4,500 pages were related to Zinke’s multi-monument review, and which showed the administration set out to increase coal, oil and gas mining access. The documents also showed that the Zinke administration’s new map largely matched a map previously promoted by longtime Utah Senator Orrin Hatch, whose plan claimed it “would resolve all known mineral conflicts for SITLA [Utah School and Institutional Trust Lands Administration] within the Bears Ears… the real [beneficiaries] are Utah schoolchildren and the people of San Juan County”, a claim the Utah Diné Bikéyah tribe disputed as hypocritical.[88]

Expenditure controversies

In September 2017, it was reported that on June 26, Zinke had chartered a jet belonging to an oil industry executive for a flight from Las Vegas to Kalispell, Montana. Zinke had been in Las Vegas to make an announcement related to public lands and to deliver a speech to the National Hockey League‘s Vegas Golden Knights, an expansion franchise owned by William P. Foley, a major donor to Zinke’s congressional campaigns. The chartered flight cost taxpayers $12,375. Costs for commercial flights between Las Vegas and Kalispell typically start at $300. Upon arrival in Kalispell, Zinke spent the night at his private residence before delivering remarks at the annual meeting of the Western Governors Association the next morning. Zinke and his staffers returned to Washington on a commercial flight the next day.[10][89][90]

Zinke used private aircraft and performed political duties in relation to an April 1 trip between St. Croix and St. Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Zinke had been in St. Croix on March 30 for an official meeting with Governor Kenneth Mapp during the day, and spent the night at a fundraiser for the Republican Party of the Virgin Islands, where attendees who pledged between $1,500 and $5,000 were allowed to have their pictures taken with Zinke. The next morning, he took a private flight costing the government $3,150 to St. Thomas to celebrate the centennial of the islands’ handover to the United States by Denmark.[91]

In December 2017, Politico reported that Zinke had booked government helicopters for more than $14,000 to travel in June and July 2017.[92] One of these trips was the swearing-in ceremony of his successor in Congress; the Department of Interior defended the use of government helicopters instead of a two-hour car drive by saying Zinke would otherwise not be able to fully participate in the ceremony.[92] An Interior spokesperson also told a Politico reporter asking about the expenses, “Shame on you for not respecting the office of a member of Congress.”[92] Another of these trips was the use of a Park Police helicopter to have a horseback ride with Vice President Mike Pence; the Interior Department justified the use of the helicopter over the three-hour car drive by saying, “the Secretary will be able to familiarize himself with the in-flight capabilities of an aircraft he is in charge of” and that Park Police staff would “provide an added measure of security to the Secretary during his travel.”[92] Zinke dismissed Politico‘s reporting as “total fabrications and a wild departure of reality” but did not identify any inaccuracies in the reporting.[93]

Inspector general investigations and other inquiries

In October 2017, the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) launched an investigation into Zinke’s use of three charter flights during his tenure as Interior Secretary.[9] In April 2018, OIG released its report, concluding that Zinke’s chartered flight to give the June 2017 speech to the Las Vegas Golden Knights was authorized “without complete information” and that the speech was not official business because Zinke did not discuss the Interior Department or his role as Interior Secretary. OIG concluded that the two other charter flights, one to Alaska and the other to the U.S. Virgin Islands, “appeared to have been reasonable as related to official DOI business.”[94][95]

In October 2017, the United States Office of Special Counsel launched a Hatch Act investigation into Zinke’s meeting with the Vegas Golden Knights.[96]

In a March 2018 Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Zinke said it was false that he had taken a private jet anywhere, noting that the charter flights he took were on aircraft with propellers, not jet engines.[97]

As of October 30, 2018, the OIG had referred Zinke to the Department of Justice for investigation, including of whether he lied to the OIG about his involvement in reviewing a tribal casino project in Connecticut.[98] The two Connecticut tribes claim that the Interior Department refused to sign off on the casino project after intense lobbying by MGM Resorts International and two Nevada Republican lawmakers.[99] Zinke said the OIG interviewed him twice about the casino decision and that he was truthful both times.[100] In late 2019, Deputy Attorney General Jeffrey Rosen stalled the probe into Zinke. Federal prosecutors had proposed to move forward with possible criminal charges against Zinke over his involvement in the casino deal.[101][102] In doing so, Rosen also prevented the Interior Department’s Office of Inspector General from making public a report about the casino deal.[101]

Trophy hunting

In November 2017, it was announced that Trump, on Zinke’s advice, wanted to lift the import ban on elephant and other big-game trophies from Zambia and Zimbabwe to the United States. A passionate hunter, Zinke justified himself to critics by saying that he had his best childhood memories of hunting with his father and that he was anxious to promote hunting for American families.[103] Critics feared that lifting the import ban would trigger a wave of U.S. hunters, and that the decision would be a major blow to the survival of the elephant species. Two days later, Trump put his decision on hold, saying that he wanted to better inform himself on the issue.[104][105][106]

In a memo dated March 1, 2018, the Fish and Wildlife Services, which operates under the Department of the Interior, declared that it would permit trophy hunting for elephants on a “case-by-case basis.”[107][108][109]

Greater sage-grouse

In 2017, Zinke took steps to unwind a 2015 plan that protected the greater sage-grouse. The Interior Department sought to change sage grouse habitat management plans in 10 states in a way that could open the sage-grouse habitat to mineral extraction and grazing. These proposals were welcomed by the oil and gas industry and condemned by environmentalists.[110][111] In April 2021, a federal judge blocked this expansion of livestock grazing in Nevada across four hundred square miles (1,000 km2) of some of the highest-priority sage-grouse habitat in the West.[112]

Migratory Bird Treaty Act

Under Zinke, the Interior Department adopted a restrictive interpretation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, issuing a guidance document stating that the killing of birds “resulting from an activity is not prohibited by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act when the underlying purpose of that activity is not to take birds.”[113] The move was opposed by a bipartisan group of 17 former top Interior Department officials, including seven former heads of migratory bird management at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who served in every administration from Nixon to Obama. In a letter sent to Zinke and members of Congress, the former officials wrote, “This legal opinion is contrary to the long-standing interpretation by every administration (Republican and Democrat) since at least the 1970s.”[114][115]

Interior Department employees

In June 2017, Zinke called for the elimination of 4,000 jobs from the Interior Department and supported the White House proposal to cut the department’s budget by 13.4%.[116] The same month, he ordered 50 Interior members of the Senior Executive Service to be reassigned, “forcing many into jobs for which they had little experience and that were in different locations.”[117] The scope of the move was unusual.[118][119] One reassigned Interior senior executive, scientist Joel Clement, published an op-ed in The Washington Post saying that the reassignment was retaliation against him “for speaking out publicly about the dangers that climate change poses to Alaska Native communities.”[118][120][121] The moves prompted the Interior Departments’ Office of Inspector General to launch a probe.[118]

In 2017, in a speech to the National Petroleum Council, Zinke said that one-third of Interior Department employees were disloyal to Trump and that “[he’s] got 30 percent of the crew that’s not loyal to the flag”. His remarks prompted objections from the Coalition to Protect America’s National Parks, Public Lands Foundation and Association of Retired Fish and Wildlife Service Employees (which called the comments “simply ludicrous, and deeply insulting”)[122] and Senator Maria Cantwell, the ranking member of the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources (who said that Zinke had a “fundamental misunderstanding of the role” of the federal civil service).[117]

Budget proposals

In 2018, as in 2017, Zinke proposed budget cuts to the Interior Department for fiscal year 2019, mostly from the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Geological Survey. His proposed budget would also have cut the Land and Water Conservation Fund to $8 million from $425 million in 2018.[123]

2018 wildfires

In August 2018, Zinke said that “environmental terrorist groups” were to blame for the wildfires in California, and that they had “nothing to do with climate change”. Fire scientists and forestry experts rejected that claim, attributing the increasingly destructive wildfires to heat and drought caused by climate change.[124] Later that month, Zinke walked back some of his earlier remarks, acknowledging that climate change played a part in the fires.[125] He also said that preventing removal of dead trees has increased the amount of flammable material and hurt timber salvaging.[126]

Calendar omissions

In October 2018, FOIA requests revealed that Zinke’s calendar, which was supposed to cover the Secretary of the Interior’s activities, contained glaring omissions. Zinke met with lobbyists and business executives on a number of occasions.[127][128] Reporting from September 2018 noted that the calendars of his activities were “so vaguely described… that the public is unable tell what he was doing or with whom he was meeting.”[129]

Departure from office

On December 15, 2018, Trump announced that Zinke would leave “the Administration at the end of the year”;[130] he later tweeted that he would name the new Secretary of the Interior the following week.[131] According to The Washington Post, Zinke had submitted his resignation the same morning.[132] Zinke himself later posted a statement on Twitter, saying, “I cannot justify spending thousands of dollars defending myself and my family against false allegations…It is better for the President and Interior to focus on accomplishments rather than fictitious allegations.”[133] His resignation came just a week after former White House Chief of Staff John Kelly‘s departure was announced.

| Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) tweeted: |

Secretary of the Interior @RyanZinke will be leaving the Administration at the end of the year after having served for a period of almost two years. Ryan has accomplished much during his tenure and I want to thank him for his service to our Nation…….

December 15, 2018

Zinke was facing several federal probes, including the “Montana land deal” in which a foundation owned by Zinke and the chairman of energy firm Halliburton, David Lesar, were accused of wrongdoing in relation to a development project in Zinke’s home town of Whitefish, Montana.[134] The Department of Justice was also investigating his use of personal email.[135]

In May 2020, Zinke criticized the investigations that led to his departure, saying they were politicized and that such investigations would result in only billionaires being able to afford to serve in a public office.[136]

Return to U.S. House of Representatives (2023–present)

Elections

2022 congressional election

In June 2021, Zinke announced his candidacy to return to the U.S. House of Representatives, this time in Montana’s 1st congressional district, which was reconstituted after the 2020 census.[137][138][139][b] He defeated Democratic nominee Monica Tranel in the general election.[140]

2024 congressional election

In 2024, Zinke defeated Democratic nominee Monica Tranel in the general election with 52% of the vote to Tranel’s 45%.[141]

Tenure

In 2023, Zinke voted against House Concurrent Resolution 21, which directed President Joe Biden to remove U.S. troops from Syria within 180 days.[142][143]

During the Gaza war, Zinke introduced legislation that would prohibit individuals who held passports from the Palestinian Authority from entering or seeking refuge in the US.[144] On his congressional website, Zinke touted the proposed bill as legislation aiming to “Expel Palestinians from the United States”.[145]

In June 2025, Zinke expressed opposition to the Senate’s version of the One Big Beautiful Bill over concerns of the proposed sale of over 1.2 million acres of public lands.[146]

In March 2026, Zinke announced that he would not run for re-election in that year’s congressional election.[147]

Personal life

Zinke married Lolita Hand on August 8, 1992. Both had been married before; Hand was a widow with a young daughter.[148] He and Hand also have two children together.[149] He is Catholic.[150]

Zinke splits his time among Washington, D.C.; Whitefish, Montana, his hometown; and Santa Barbara, California, his wife’s hometown.[149] In 2021, Politico reported that he no longer resided at his Whitefish house and spent more time in Santa Barbara.[151] Zinke was formerly Missouri Synod Lutheran.[152][153]

Awards and decorations

Electoral history

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 1,452 | 69.37 | |

| Republican | Suzanne Brooks | 641 | 30.63 | |

| Total votes | 2,093 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 5,498 | 54.60 | |

| Democratic | Brittany MacLean | 4,571 | 45.40 | |

| Total votes | 10,069 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 43,766 | 33.25 | |

| Republican | Corey Stapleton | 38,591 | 29.32 | |

| Republican | Matt Rosendale | 37,965 | 28.84 | |

| Republican | Elsie Arntzen | 9,011 | 6.85 | |

| Republican | Drew Turiano | 2,290 | 1.74 | |

| Total votes | 131,623 | 100 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 203,871 | 55.41 | |

| Democratic | John Lewis | 148,690 | 40.41 | |

| Libertarian | Mike Fellows | 15,402 | 4.19 | |

| Total votes | 367,963 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke (incumbent) | 144,660 | 100.0 | |

| Total votes | 144,660 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke (incumbent) | 285,358 | 56.19 | |

| Democratic | Denise Juneau | 205,919 | 40.55 | |

| Libertarian | Rick Breckenridge | 16,554 | 3.26 | |

| Total votes | 507,831 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 35,601 | 41.7 | |

| Republican | Albert Olszewski | 33,927 | 39.7 | |

| Republican | Mary Todd | 8,915 | 10.4 | |

| Republican | Matthew Jette | 4,973 | 5.8 | |

| Republican | Mitch Heuer | 1,953 | 2.3 | |

| Total votes | 85,369 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke | 123,102 | 49.65 | |

| Democratic | Monica Tranel | 115,265 | 46.49 | |

| Libertarian | John Lamb | 9,593 | 3.87 | |

| Total votes | 247,960 | 100% | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke (incumbent) | 66,409 | 73.74 | |

| Republican | Mary Todd | 23,647 | 26.26 | |

| Total votes | 90,056 | 100.0 | ||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Ryan Zinke (incumbent) | 168,529 | 52.3 | |

| Democratic | Monica Tranel | 143,783 | 44.62 | |

| Libertarian | Dennis Hayes | 9,954 | 3.09 | |

| Total votes | 322,226 | 100.0 | ||

See also

- 2018 United States Senate election in Montana

- Environmental policy of the first Trump administration

- List of Department of the Interior appointments by Donald Trump

- List of United States representatives in the 115th Congress

- List of Montana state senators

- Whitefish Energy

References

Notes

- ^ From 1913 to 1993, Montana had two congressional seats, after which, the 2nd district was eliminated and the remaining seat was elected at-large.

- ^ Montana had been split between two districts from 1919 to 1993, but for the next three decades had been represented by a single member.

Citations

- ^ “Montana Legislature: Ryan Zinke”. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ Rott, Nathan (December 15, 2018). “Ryan Zinke is Leaving the Interior Department, Trump Tweets”. NPR. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Angel, Kristi. “Certificate of release”. The Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “Donald Trump picks Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke for interior secretary”. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “Zinke favors increasing ‘uses,’ boosting production of federal lands”. Spokesman.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Steele, Jeanette. “Zinke marks 1st Navy SEAL for Cabinet slot”. The San Diego Union-Tribune. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Killough, Ashley; Barrett, Ted (March 1, 2017). “Senate approves Trump’s nominee for Interior”. CNN. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved March 1, 2017.

- ^ Turkewitz, Julie (April 16, 2018). “Ryan Zinke Is Opening Up Public Lands. Just Not at Home”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2018.

- ^ a b “Ryan Zinke’s use of charter flights under investigation by interior department”. TheGuardian.com. Associated Press. October 2, 2017. Archived from the original on April 14, 2019. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Green, Miranda (October 4, 2017). “Ryan Zinke, Golden Knights meeting under investigation”. CNN. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet; Dawsey, Josh; Rein, Lisa (November 1, 2018). “White House concerned Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke violated federal rules”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 13, 2021. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Lefebvre, Ben; Colman, Zack (October 30, 2018). “Zinke’s heir apparent ready to step in”. Politico. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Knickmeyer, Ellen; Brown, Matthew; Press, Jonathan Lemire | The Associated (December 15, 2018). “Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke resigning, cites “vicious” attacks”. The Denver Post. Archived from the original on January 1, 2019. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- ^ Cama, Timothy; Green, Miranda (December 15, 2018). “Interior chief Zinke to leave administration“. The Hill. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Holden, Emily; Milman, Oliver (December 15, 2018). “Embattled interior secretary Ryan Zinke steps down after series of scandals”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 28, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ “Ryan Zinke broke ethics rules while leading Trump’s Interior Dept., watchdog finds”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on February 16, 2022. Retrieved February 16, 2022.

- ^ Rein, Lisa; Phillips, Anna (August 24, 2022). “Ex-interior secretary Zinke lied to investigators in casino case, watchdog finds”. Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 25, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2022.

- ^ Zinke, Ryan (November 29, 2016). American Commander: Serving a Country Worth Fighting For and Training the Brave Soldiers Who Lead the Way. HarperCollins Christian Publishing. ISBN 9780718081676. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2020 – via Google Books.

- ^ “Jean Montana Harlow Petersen, 65”. dailyinterlake.com. Archived from the original on September 23, 2017.

- ^ Zelisko, Larry (February 8, 2017). “Larry the Answer Guy: 4 Eagle Scouts in Trump’s Cabinet”. USA Today. Archived from the original on June 13, 2018. Retrieved July 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c Johnson, Charles S. (September 27, 2014). “U.S. House candidate profile: Ryan Zinke”. Ravelli Republic. Hamilton, Montana. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved December 14, 2016.

- ^ “Starting lineups”. Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. September 24, 1983. p. 2C. Archived from the original on April 4, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d Smita Nordwall (December 15, 2016). “Who is Ryan Zinke?”. Voice of America. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 26, 2017.

- ^ a b c Ganim, Sara. “Ryan Zinke refers to himself as a geologist. That’s a job he’s never held”. CNN. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Herron, Elise. “Secretary of Interior Ryan Zinke Says a 34-Year-Old Undergrad Degree From the University of Oregon Qualifies Him As a Geologist. Others Disagree”. Willamette Week. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Charles (August 9, 2014). “Zinke releases some Navy records on SEAL career; Dems seek more”. Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ McEwen, Scott; Miniter, Richard (February 25, 2014). Eyes on Target: Inside Stories from the Brotherhood of the U.S. Navy SEALs. Center Street. ISBN 9781455575688. Archived from the original on March 8, 2023. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Drew, Christopher; Naylor, Sean D. (January 16, 2017). “Interior Nominee Promotes Navy SEAL Career, While Playing Down ‘Bad Judgment’“. The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2018. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ a b Charles S. Johnson, Zinke’s Navy records show praise, lapses over travel claims Archived February 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Missoulian (October 27, 2014).

- ^ “PN1110 — Navy”. U.S. Congress. June 27, 2000. Archived from the original on March 3, 2017. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ “Montana State Senator Ryan Zinke Joins STWA’s Board of Directors :: QS Energy, Inc. (QSEP)”. www.qsenergy.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Charles S. (July 16, 2014). “U.S. House candidate Zinke amasses more wealth than Lewis”. Missoulian. Archived from the original on October 23, 2017. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ “Ryan Zinke says he’s now trying to make a cryptocurrency company “great again”“. Vice News. January 25, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved January 28, 2019.

- ^ a b swissinfo.ch, Matthew Allen (January 29, 2019). “Zinke ditches ‘hateful’ politics for blockchain future”. SWI swissinfo.ch. Archived from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Natter, Ari; Dlouhy, Jennifer A. (July 23, 2019). “Ryan Zinke Is Now Taking Clients From Industries He Oversaw in Trump’s Cabinet”. Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on May 30, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c Zarembo, Alan (October 24, 2014). “Does being a veteran help candidates? A Montana politician hopes so”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 15, 2017. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ “Zinke may have Trumped McMorris Rodgers for Interior secretary”. Spokesman.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “Congressional Meet and Greet – Congressman Ryan Zinke (R-MT) | Stay Informed | K&L Gates”. www.klgates.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “Examining the Fresh Faces in Congress | SEMA”. www.sema.org. Archived from the original on March 4, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “State Automotive Enthusiast Leadership Caucus | SEMA”. www.sema.org. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ “Congressional 2008 Political Courage Test”. www.ontheissues.org. Archived from the original on August 12, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Tim (December 14, 2016). “Trump’s Interior Nominee Was for Climate Action Before He Was Against It”. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

In 2010, as a member of the Montana Legislature, he … asked President Barack Obama and then-Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi to push through sweeping climate and clean-energy legislation.

- ^ Kaczynski, Andrew (April 16, 2018). “Zinke invited birthers, questioned Obama’s college records on his radio show in 2013”. CNN. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved April 16, 2018.

- ^ Johnson, Charles S. (July 10, 2011). “Livingstone taps Zinke as running mate”. Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on October 13, 2017. Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ “Archived Election Results”. sos.mt.gov. Archived from the original on June 1, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ a b Redden, Molly (November 1, 2013). “GOP congressional candidate using campaign money scheme pioneered by…Stephen Colbert”. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on March 2, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c Soo Rin Kim (December 14, 2016). “Zinke’s nomination could bring questions about super PAC ties – OpenSecrets Blog”. OpenSecrets. Archived from the original on May 17, 2018. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ Kaczynski, Andrew; Massie, Chris (April 24, 2018). “Zinke put birther conspiracy theorist on super PAC board”. CNN. Archived from the original on October 12, 2020. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ “Ryan Zinke Announces Statewide Bus Tour”. April 30, 2014. Archived from the original on May 18, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2014.

- ^ *Molly Redden, Meet the GOP Congressional Candidate Who Called Hillary Clinton the “Antichrist” Archived December 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Mother Jones (February 4, 2014).

- Cameron Joseph, House candidate calls Clinton ‘Antichrist’, The Hill (January 31, 2014).

- ^ Charles S. Johnson, Zinke’s abortion votes draw criticism, but he’s pro-life Archived August 30, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Billings Gazette (May 4, 2014) (also published in the Missoulian ).

- ^ Southall, -Ashley. “Montana Election Results”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ Dennison, Mike. “Zinke and Juneau raising big bucks for U.S. House battle”. KXLF. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- ^ “Election 2016 Results: Bullock Re-elected Governor, Zinke Cruises”. Flathead Beacon. November 8, 2016. Archived from the original on January 15, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ^ Wadley, Will (April 15, 2015). “MT Republicans push repeal of ‘Death Tax’“. KECI. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016.

- ^ Doering, Christopher (April 16, 2015). “Farm groups urge Senate to follow House and repeal estate tax”. Great Falls Tribune. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021.

- ^ Coffman, Keith; Johnson, Eric M. (December 27, 2016). “Montana Lawmakers Unite To Denounce Neo-Nazi Rally Plans”. Forward. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2016.

- ^ Fletcher-Frye, Jessica. “Loebsack visits Columbus to discuss legislation for rural schools”. The Quad-City Times. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Frederica, Wilson (February 26, 2015). “H.Amdt.42 to H.R.5 – 114th Congress (2015–2016) – Amendment Text”. www.congress.gov. Archived from the original on August 9, 2018. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet (December 13, 2016). “Trump taps Montana congressman Ryan Zinke as interior secretary”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Egan, Timothy (January 19, 2018). “Opinion | The Mad King Flies His Flag”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ Friedman, Lisa (January 4, 2018). “Trump Moves to Open Nearly All Offshore Waters to Drilling”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 12, 2018. Retrieved January 20, 2018.

- ^ a b c Harvey, Chelsea (December 21, 2016). “Trump’s pick for Interior secretary can’t seem to make up his mind about climate change”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Mooney, Chris; Erickson, Andee (January 17, 2017). “Ryan Zinke admits humans ‘influence’ climate change. But scientists say we’re the ‘dominant cause.’“. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 5, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Harder, Amy; Bender, Michael C. (December 13, 2016). “Donald Trump Picks Montana Congressman Ryan Zinke as Interior Secretary”. The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 24, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Lutey, Tom (July 15, 2016). “Zinke resigns delegate post over public lands disagreement; still will speak at RNC”. Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- ^ “Committees and Caucuses | Congressman Ryan Zinke”. January 26, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ “Caucus Memberships”. Congressional Western Caucus. Retrieved April 11, 2025.

- ^ Ioffe, Julia (June 20, 2018). “The Real Story of Donald Trump Jr”. GQ. Archived from the original on June 21, 2018. Retrieved June 21, 2018.

It was Don who recommended that former Navy SEAL Ryan Zinke—a fellow hunting enthusiast who once reportedly referred to Hillary Clinton as “the Antichrist”—should be tapped as Trump’s secretary of the interior.

- ^ “Trump picks Montana Rep. Zinke for interior post”. Associated Press. December 15, 2016. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Fears, Darryl (January 31, 2017). “Ryan Zinke is one step closer to becoming interior secretary”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Fears, Darryl (March 1, 2017). “Senate confirms Ryan Zinke as interior secretary”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 13, 2018. Retrieved April 18, 2021.

- ^ McLaughlin, Seth (February 12, 2021). “Jon Tester, Montana Democrat, backs interior pick Republican Ryan Zinke”. The Washington Times. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ “Pence swears in Zinke as Interior Secretary”. Reuters. March 1, 2017. Archived from the original on August 9, 2017. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Haag, Matthew (March 2, 2017). “The Interior Secretary, and the Horse He Rode in On”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 2, 2017.

- ^ “Trump cabinet member trots through Washington on horseback”. BBC News. March 2, 2017. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ “Montana Secretary of State”. mtelectionresults.gov. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2017.

- ^ Wolfgang, Ben (March 2, 2017). “Trump’s team scraps Obama-era ban on lead bullets”. The Washington Times. Archived from the original on April 25, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Cama, Timothy (March 2, 2017). “Interior secretary repeals ban on lead bullets”. The Hill. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Reilly, Patrick (March 3, 2017). “Lead shot OK’d for federal lands: what does that mean for conservation?”. The Christian Science Monitor. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ a b Daly, Matthew (March 2, 2017). “New Interior Secretary Zinke reverses lead-ammunition ban”. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 12, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ a b c “Lead Ammunition Poisons Wildlife But Too Expensive To Change, Hunters Say”. NPR. February 20, 2017. Archived from the original on May 12, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ Fears, Darryl; Eilperin, Juliet (June 12, 2017). “Interior secretary recommends Trump consider scaling back Bears Ears National Monument”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 19, 2018. Retrieved June 13, 2017.

- ^ Tobias, Jimmy (August 24, 2017). “Under threat: the three national monuments in Trump’s sights”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet; Fears, Darryl (August 24, 2017). “Interior secretary recommends Trump alter at least three national monuments, including Bears Ears”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 9, 2018. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ a b Eilperin, Juliet (December 5, 2017). “Zinke backs shrinking more national monuments and shifting management of 10”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ Candee, Adam (December 5, 2017). “Zinke recommends shrinking Gold Butte National Monument”. Las Vegas Sun. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- ^ “Oil and coal drove Trump’s call to shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase, according to insider emails released by court order”. The Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ Harwell, Drew; Rein, Lisa (September 28, 2017). “Zinke took $12,000 charter flight home in oil executive’s plane, documents show”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 20, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2017.

- ^ Stanton, Zack (September 28, 2017). “Interior Secretary Zinke traveled on charter, military planes”. Politico. Archived from the original on February 26, 2021. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- ^ Lefebvre, Ben; Whieldon, Esther (October 5, 2017). “Trump’s Interior chief ‘hopping around from campaign event to campaign event’“. Politico. Archived from the original on March 24, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Lefebvre, Ben (December 8, 2017). “Zinke booked government helicopters to attend D.C. events”. Politico. Archived from the original on May 10, 2018. Retrieved December 8, 2017.

- ^ Diaz, Daniella; Wallace, Gregory (December 10, 2017). “Zinke: Reports on helicopter use a ‘wild departure from reality’“. CNN. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved December 10, 2017.

- ^ “Watchdog: Zinke charter flight approved without full info”. Tampa Bay Times. Associated Press. April 16, 2018. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018.

- ^ Investigative Report on Secretary Zinke’s Use of Chartered and Military Aircraft Between March and September 2017 (PDF) (Report). Office of the Inspector General, United States Department of the Interior. April 16, 2018. 17-104. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 17, 2018.

- ^ Green, Miranda (April 6, 2018). “Watchdog: Zinke could have avoided charter flight after meeting with Las Vegas hockey team”. The Hill. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- ^ Lemire, Jonathan (March 14, 2018). “Cabinet chaos: Trump’s team battles scandal, irrelevance”. Associated Press News. Archived from the original on March 14, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Zapotsky, Matt (January 3, 2019). “Feds investigating whether former Interior Secretary Zinke lied about East Windsor casino”. Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Juliano, Nick (October 17, 2018). “Tribe says ‘improper political influence’ led Zinke to scuttle casino”. Politico. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ Brown, Matthew (January 3, 2019). “Ryan Zinke denies report that he lied to Interior investigators”. The Billings Gazette. Archived from the original on January 31, 2019. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ a b “Senior Justice Dept. official stalled probe against former interior secretary Ryan Zinke, sources say”. The Washington Post. November 12, 2020. Archived from the original on December 15, 2020. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Benner, Katie (November 11, 2020). “Barr’s Decision on Voter Fraud Inflames Existing Tensions With Anticorruption Prosecutors”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Timothy Cama: Trump to allow imports of African elephant trophies, The Hill (November 11, 2017).

After targeting elephants, Interior Department puts African lions in the crosshairs Archived November 17, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, A Humane Nation, (November 16, 2017). - ^ Eli Stokols, Trump delays policy allowing big game trophy body parts to be imported to US Archived November 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Wall Street Journal (November 18, 2017).

- ^ Emily Tillett, Trump reverses Obama-era ban on import of elephant trophies from Zimbabwe Archived November 18, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, CBS News (November 16, 2017).

- ^ Ashley Hoffman: People on Twitter Are Upset That President Trump Lifted an Elephant Trophy Ban Archived January 25, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, Time (November 16, 2017).

- ^ Rosenberg, Eli (March 6, 2018). “Trump administration quietly makes it legal to bring elephant parts to the U.S. as trophies”. The Washington Post. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Nuwer, Rachel (March 7, 2018). “U.S. Lifts Ban on Some Elephant and Lion Trophies”. The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Dwyer, Colin (March 6, 2018). “Trump Administration Quietly Decides — Again — To Allow Elephant Trophy Imports”. NPR. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Friedman, Lisa (September 28, 2017). “Interior Department to Overhaul Obama’s Sage Grouse Protection Plan”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 2, 2018.

- ^ Rott, Nathan (August 7, 2017). “Trump Administration Revises Conservation Plan For Western Sage Grouse”. NPR. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018.

- ^ “U.S. judge blocks Nevada grazing project as sage grouse dwindle”. KTLA. Associated Press. April 1, 2021. Archived from the original on April 1, 2021. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Fears, Darryl; Grandoni, Dino (April 13, 2018). “The Trump administration has officially clipped the wings of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 26, 2018.

- ^ Hannah Waters, 17 Former Federal Officials to Zinke: Don’t Change the Migratory Bird Treaty Act Archived April 17, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Audubon Society (January 11, 2018).

- ^ Grandoni, Dino (January 12, 2018). “The Energy 202: Ryan Zinke’s move is not for the birds, say 17 former Interior officials”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 17, 2018.

- ^ Interior chief wants to shed 4,000 employees in department shake-up Archived December 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post (June 21, 2017).

- ^ a b Darryl Fears & Juliet Eilperin, Zinke says a third of Interior’s staff is disloyal to Trump and promises ‘huge’ changes Archived December 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post (September 2, 2017).

- ^ a b c Joe Davidson, Interior’s ‘unusual’ transfer of senior executives spurs official probe Archived December 22, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post (September 12, 2017).

- ^ Juliet Eilperin & Lisa Rein, Zinke moving dozens of senior Interior Department officials in shake-up Archived April 30, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post (June 16, 2017).

- ^ Rott, Nathan (July 19, 2017). “Climate Scientist Says He Was Demoted For Speaking Out on Climate Change”. NPR. Archived from the original on October 25, 2017. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Clement, Joel (July 19, 2017). “I’m a scientist. I’m blowing the whistle on the Trump administration”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Shogren, Elizabeth (October 3, 2017). “What drove an Interior whistleblower to dissent?”. High Country News. Archived from the original on February 27, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2021.

- ^ Kuglin, Tom (May 10, 2018). “Montana senators question Zinke’s proposed cuts to Land and Water Conservation Fund”. Independent Record. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ Logan, Erin B. (August 16, 2018). “Ryan Zinke blames ‘environmental terrorist groups’ for severity of California wildfires”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on August 16, 2018. Retrieved August 16, 2018.

- ^ Fountain, Henry (August 17, 2018). “Climate Has a Role in Wildfires? No. Wait, Yes”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved August 31, 2018.

- ^ Segers, Grace (August 16, 2018). “Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke acknowledges role of climate change in wildfires”. CBS News. Archived from the original on September 2, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Sara Ganim; Gregory Wallace. “Zinke’s calendar omissions date back to his very first day in office”. CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Sara Ganim; Gregory Wallace; Aaron Kessler. “Zinke kept some meetings off public calendar”. CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ Sara Ganim; Gregory Wallace; Ellie Kaufman. “Latest Zinke calendars stripped of most details about his meetings”. CNN. Archived from the original on October 24, 2018. Retrieved October 24, 2018.

- ^ “Donald J. Trump on Twitter”. Twitter. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Tatum, Sophie; Fox, Lauren; Wallace, Gregory (December 15, 2018). “Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke to leave Trump administration at end of the year”. CNN. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Eilperin, Juliet; Dawsey, Josh; Fears, Darryl (December 15, 2018). “Interior Secretary Zinke resigns amid investigations”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Zinke, Secretary Ryan (December 15, 2018). “I love working for the President and am incredibly proud of all the good work we’ve accomplished together. However, after 30 years of public service, I cannot justify spending thousands of dollars defending myself and my family against false allegations. Full statement attached.pic.twitter.com/gwo75SA6bM”. @SecretaryZinke. Archived from the original on December 15, 2018. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Riotta, Chris (December 15, 2018). “Ryan Zinke: Trump announces Secretary of Interior is to step down”. The Independent. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved December 15, 2018.

- ^ Juliano, Nick (July 30, 2019). “DOJ investigating Zinke’s use of personal email, inspector tells lawmakers”. Politico. Archived from the original on March 18, 2021. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ Beitsch, Rebecca (May 18, 2020). “Ex-Interior chief rips attacks, says being a billionaire ‘can’t be a prerequisite’ for public office”. The Hill. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ “Zinke’s 2022 campaign for MT congressional seat is official”. KTVH-DT. June 3, 2021. Archived from the original on June 12, 2021. Retrieved June 12, 2021.

- ^ Cunningham, Meg (April 29, 2021). “Former Trump official Ryan Zinke files paperwork for congressional seat in Montana”. ABC News. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Markay, Lachlan (April 29, 2021). “Former Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke signals Montana House bid”. Axios. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 29, 2021.

- ^ Kuglin, Tom (November 10, 2022). “AP: Zinke wins western House seat”. Helenair.com. Archived from the original on November 10, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ^ “Montana First Congressional District Election Results”. The New York Times. November 5, 2024. Retrieved March 13, 2025.

- ^ “H.Con.Res. 21: Directing the President, pursuant to section 5(c) of … — House Vote #136 — Mar 8, 2023”. March 8, 2023. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ “House Votes Down Bill Directing Removal of Troops From Syria”. Associated Press. March 8, 2023. Archived from the original on March 10, 2023. Retrieved March 10, 2023.

- ^ Hawley, George (2023), “Are Right-Wing Americans Really More Tolerant of Political Violence?”, The Palgrave Handbook of Left-Wing Extremism, vol. 2, Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature Switzerland, pp. 41–52, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-36268-2_3, ISBN 978-3-031-36267-5, retrieved November 4, 2023

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Bump, Philip (November 6, 2023). “A disgraced former Trump official wants to deport Palestinians”. The Washington Post. Retrieved January 9, 2024.

- ^ Coleman, Jocelyn (June 27, 2024). “Public land sales pose passage problems”. The Hill. Retrieved June 28, 2025.

- ^ “Zinke announces he won’t seek reelection”. The Hill. March 2, 2026. Retrieved March 2, 2026.

- ^ Ryan Zinke with Scott McEwen, American Commander: Serving a Country Worth Fighting For and Training the Brave Soldiers Who Lead the Way (W Publishing Group, 2016), p. 207.

- ^ a b Julie Turkewitz, He Will Soon Run a Fifth of the Nation. Meet Ryan Zinke. Archived March 2, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (March 1, 2017).

- ^ Miller, Blair (October 14, 2024). “Zinke and Tranel participate in western district debate as ballots reach mailboxes • Daily Montanan”. Daily Montanan. Retrieved October 15, 2024.

- ^ Miranda Green (October 8, 2021). “Ryan Zinke is Running for Office Again in Montana. On Instagram, He’s Often in Santa Barbara”. POLITICO. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ “RollCall.com – Member Profile – Ryan Zinke, R”. media.cq.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- ^ “Members of Congress: Religious Affiliations”. Pew Research Center Religion & Public Life Project. January 5, 2015. Archived from the original on October 30, 2019. Retrieved March 8, 2017.

- ^ “Zinke releases some Navy records on SEAL career; Dems seek more”. Montana Standard. August 10, 2014. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ a b Carter, Troy (September 10, 2014). “Review of Zinke’s Navy record comes out clean”. Bozeman Daily Chronicle. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ^ “2008 Legislative Primary Election Results” (PDF). sosmt.gov. Montana Secretary of State. 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ “2008 Legislative General Election Results” (PDF). sosmt.gov. Montana Secretary of State. November 2008. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ “2014 Statewide Montana Primary Election Canvas” (PDF). Montana Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 28, 2014. Retrieved July 23, 2014.

- ^ “2014 STATEWIDE GENERAL ELECTION CANVASS” (PDF). Montana Secretary of State. November 4, 2014. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ “2016 Statewide Montana Primary Election” (PDF). Montana Secretary of State. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 10, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- ^ “2016 General Election”. Montana Secretary of State. Archived from the original on February 8, 2019. Retrieved December 9, 2016.

- ^ “2022 Statewide Primary Election Canvass”. 2022 Primary Election. Montana Secretary of State. June 7, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ “2022 GENERAL ELECTION – UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE”. Secretary of State of Montana. November 8, 2022. Archived from the original on June 3, 2020. Retrieved November 14, 2022.

- ^ “Montana 2024 Elections: Montana Primary Results”. Montana Free Press. July 3, 2024. Retrieved October 30, 2024.

- ^ “2024 GENERAL ELECTION – UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE”. Montana Secretary of State. November 5, 2024. Retrieved January 30, 2025.

External links

- Congressman Ryan Zinke official U.S. House website

- Zinke for Congress campaign website

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN