Summary

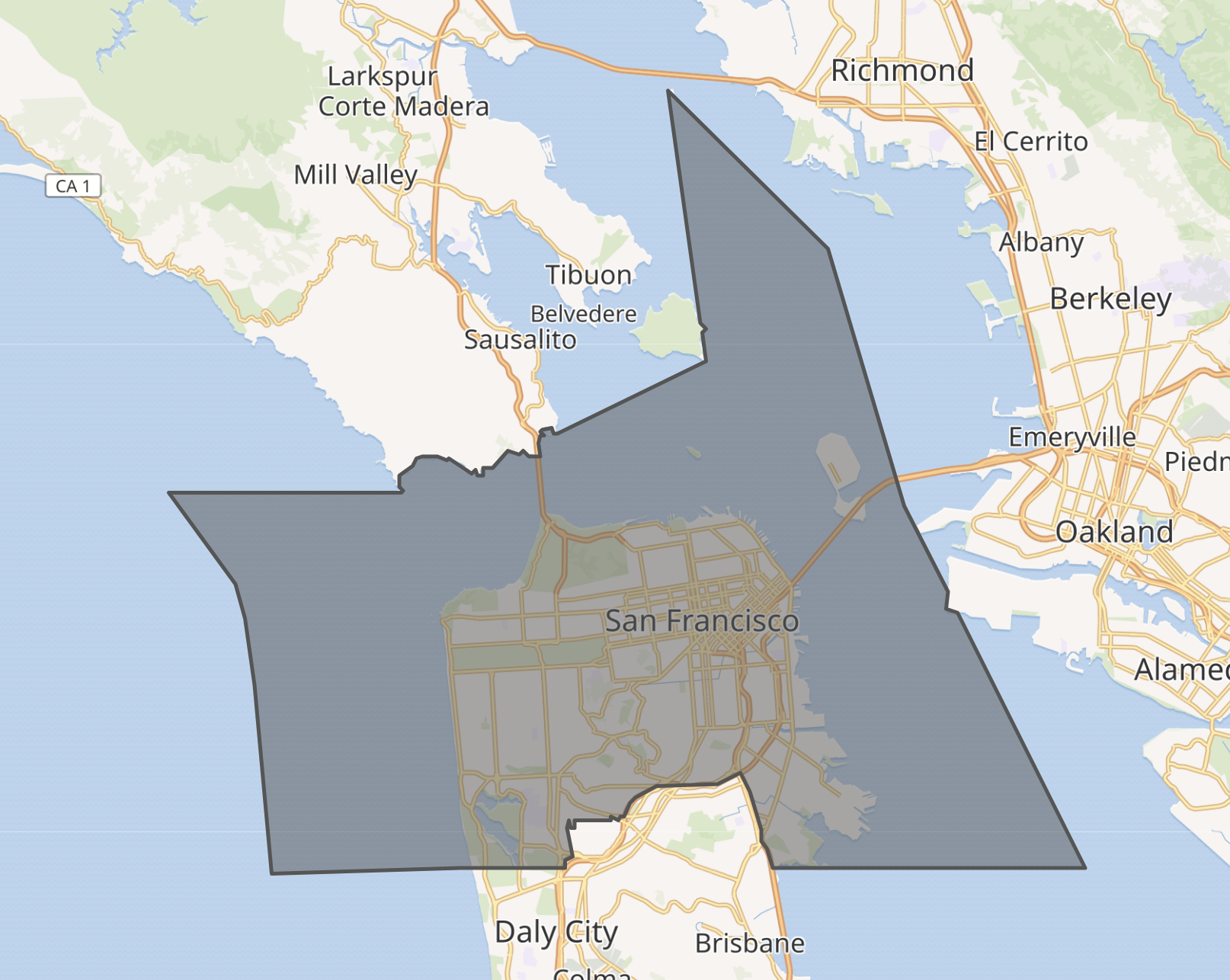

Current Position: US Representative of CA District 11 since 1987 (formerly 12th)

Affiliation: Democrat

Other positions: Former Speaker of the House

District: entirely in San Francisco

Upcoming Election:

Quotes:

For more than a decade Dodd-Frank has stood as a pillar of Democrats’ leadership to protect families’ financial security. After reckless actions by predatory lenders & Wall Street ignited the Great Recession, Democrats delivered an historic transformation of our financial system.

Pelosi was born and raised in Baltimore, and is the daughter of mayor and congressman Thomas D’Alesandro Jr.

Nancy Pelosi Holds Press Conference on Jan. 6th Select Committee | NBC News

OnAir Post: Nancy Pelosi CA-11

News

About

Source: Government page

Nancy Pelosi has represented San Francisco in Congress for more than 35 years. She served as the 52nd Speaker of the House of Representatives, having made history in 2007 when she was elected the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House. Pelosi made history again in January 2019 when she regained her position second-in-line to the presidency – the first person to do so in more than six decades. Speaker Pelosi is the chief architect of generation-defining legislation under two Democratic administrations, including the Affordable Care Act and the American Rescue Plan. Pelosi is fighting For The People: working to lower costs, increase paychecks and create jobs for American families.

Nancy Pelosi has represented San Francisco in Congress for more than 35 years. She served as the 52nd Speaker of the House of Representatives, having made history in 2007 when she was elected the first woman to serve as Speaker of the House. Pelosi made history again in January 2019 when she regained her position second-in-line to the presidency – the first person to do so in more than six decades. Speaker Pelosi is the chief architect of generation-defining legislation under two Democratic administrations, including the Affordable Care Act and the American Rescue Plan. Pelosi is fighting For The People: working to lower costs, increase paychecks and create jobs for American families.

Speaker Pelosi led House Democrats for 20 years and previously served as House Democratic Whip. In 2013, she was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame at a ceremony in Seneca Falls, the birthplace of the American women’s rights movement.

Under the Biden-Harris Administration, Speaker Pelosi led the House in crafting and enacting the American Rescue Plan. This life-saving legislation turned the tide of the pandemic: getting vaccines into hundreds of millions of Americans’ arms, delivering direct assistance to families in need, creating millions of new jobs, supporting teachers, police officers, firefighters, transit workers and other frontline heroes, and returning children safely to schools. Speaker Pelosi also engineered House passage of the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which is strengthening roads, bridges, ports, water systems and broadband access in communities across the country while rebuilding America’s middle class. Her leadership on the House-passed Build Back Better Act paved the way for the enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act: historic action to bring down the cost of prescription drugs, lower health care premiums, deliver the most consequential climate action in human history and pay down the federal deficit. Pelosi was a key negotiator in assembling the bipartisan and bicameral CHIPS and Science Act, which is powering America to world leader status in semiconductor production and scientific discovery, while building a diverse and inclusive STEM workforce in communities across the country.

In the 111th Congress, Speaker Pelosi led the House passage of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act to rescue the nation from the depths of the financial crisis, helping create or save millions of American jobs. Her leadership in enshrining the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act into law helped restore the ability of women to fight pay discrimination in the courts and ensure they too could participate in the economic recovery. Pelosi also led the Congress in enacting the historic Dodd-Frank reforms to rein in big banks and create strong protections for consumers, seniors and Servicemembers.

Speaker Pelosi has long been a champion for families’ health care. Pelosi was the architect of the landmark Affordable Care Act, which has guaranteed protections for all Americans with pre-existing medical conditions, forbid insurers from treating being a woman as a pre-existing condition, ended annual and lifetime limits on health coverage, and provided affordable health coverage for tens of millions more Americans. As Democratic Leader in 2017, Pelosi led the charge to defend American families from Republicans’ monstrous “Trumpcare” legislation: mobilizing a massive nationwide campaign in support of the ACA and powering Democrats back into the Majority in 2018. For decades, Pelosi has also been a relentless leader on reducing the costs of prescription drugs by empowering the federal government to negotiate drug prices and capping out-of-pocket costs for seniors: action enshrined into law in the Inflation Reduction Act.

Pelosi has made the climate crisis the flagship issue of her Speakership. In 2022, Speaker Pelosi delivered House passage of the Inflation Reduction Act – which contained the biggest, boldest climate action in history. This law included many House-crafted provisions to accelerate America’s transition to a clean energy future: putting the nation on a path to slash carbon pollution by 40 percent by 2030, while creating millions of new jobs and advancing environmental justice. This builds on progress from Pelosi’s first Speakership: in 2007, she enacted comprehensive energy legislation that raised vehicle fuel efficiency standards for the first time in three decades and made a game-changing commitment to America’s homegrown biofuels. In 2009, she led passage of the American Clean Energy and Security Act to create clean energy jobs, combat the climate crisis and transition America to a clean energy economy.

A leader on conservation and the environment at home and abroad, Pelosi authored legislation to create the Presidio Trust and transform San Francisco’s former military post into an urban national park. She also secured passage of the “Pelosi Amendment” in 1989, now a global tool used to assess the potential environmental impacts of development.

Speaker Pelosi has been a force for accountability, transparency and participation in government. Under her leadership, the House enacted the toughest ethics reform legislation in the history of the Congress – including the creation of an independent ethics panel. Pelosi also led an historic legislative campaign for voting rights, passing two once-in-a-generation pieces of legislation. The For The People Act would expand access to the ballot, clean up corruption in government, outlaw partisan gerrymandering and combat dark money in politics, and the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act would restore the federal government’s power to defend access to the ballot across the country.

Speaker Pelosi is a steadfast defender of the Constitution and the rule of law. In 2019, after President Trump violated his oath of office by soliciting foreign intervention in the upcoming presidential election and withholding Congressionally appropriated assistance to Ukraine, the Democratic House launched an investigation that resulted in the third presidential impeachment in history. In 2021, after President Trump incited a violent insurrection targeting the U.S. Capitol and sought to overturn the results of the election, the House impeached Trump a second time. Speaker Pelosi then led the House in creating the bipartisan Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol.

Pelosi has been a staunch champion of America’s national security and a respected voice abroad in promoting democratic values. She is the longest-serving Member of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence in history: serving from 1993-2003, including as Ranking Member from 2000-2003, and later in an ex officio capacity. As Speaker, she marshaled billions of dollars in security, economic and humanitarian assistance for the people of Ukraine after Russia’s unlawful invasion in February 2022. She orchestrated an overwhelmingly bipartisan and bicameral effort to impose swift and severe consequences on Russia, including a ban on the import of Russian energy and the revocation of normal trade relations.

For decades, Pelosi has offered a powerful voice for human rights around the world – especially speaking out on behalf of Uyghur communities, the citizens of Hong Kong, the Tibetan people and all those oppressed by the government of China. In 2022, she became the first House Speaker and highest-ranking U.S. official to travel to Taiwan in a quarter-century: an historic visit that reaffirmed America’s unwavering support for the people of Taiwan. As Democratic Leader, she helped strengthen America’s security by securing the votes needed to defeat Republicans’ effort to disapprove of President Obama’s Iran Nuclear Agreement, a landmark policy that halted Iran’s progress toward a nuclear weapon.

Speaker Pelosi has long been a leader in the fight for full equality. She spearheaded the historic repeal of the discriminatory “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, allowing gay and lesbian Americans to openly serve their country. She passed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, a law advancing justice for the millions of Americans at risk of violence for being who they are. As Speaker, she twice passed the watershed Equality Act: ensuring justice for the LGBTQ community in the workplace and in every place. Pelosi also led the charge to fight back against the Trump Administration’s hateful ban on transgender Servicemembers. In one of her final acts as Speaker, she presided over passage of the landmark Respect for Marriage Act to uphold marriage equality under federal law.

While serving as Democratic Leader, Pelosi’s strength at the negotiating table wrested critical legislative victories out of the GOP majority. In the 114th Congress, she achieved an historic bipartisan agreement to strengthen Medicare: ending the cycle of expensive “Doc Fix” patches and building a system that improves accuracy of payments and quality of care. She also delivered significant funding increases for key Democratic priorities, including the fight against the opioid epidemic, support for NIH medical research and permanent authorization of the World Trade Center Health Program.

Negotiating directly with the Trump Administration, Speaker Pelosi was crucial to securing vital relief for families and small businesses in early COVID-19 pandemic relief laws. Additional key accomplishments signed into law during her four terms as Speaker include: landmark gun violence prevention measures; legislation to expand educational opportunities while reforming the financial aid system; legislation to provide health care for eleven million American children; new protections against hate crimes; an increase in the minimum wage for the first time in a decade; the largest college aid expansion since the GI bill; new funding to address PFAS forever chemicals; a new GI education bill for veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars; and increased services for veterans, caregivers and the Veterans Administration. With Speaker Pelosi at the helm, the House also advanced important legislation to ensure equal pay for equal work; save lives through a reinstatement of the Assault Weapons Ban and mandatory background checks for gun purchases; protect pregnant workers against discrimination; reform America’s broken immigration system and secure justice for Dreamers and farmworkers; care for veterans exposed to toxic chemicals in the line of duty; and protect borrowers from unfair lending practices.

Pelosi comes from a strong family tradition of public service. Her late father, Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., served as Mayor of Baltimore for twelve years, after representing the city for five terms in Congress. Her brother, Thomas D’Alesandro III, also served as Mayor of Baltimore. She graduated from Trinity College in Washington, D.C. She and her husband, Paul Pelosi, a native of San Francisco, have five grown children and ten grandchildren.

Personal

Full Name: Nancy Pelosi

Gender: Female

Family: Husband: Paul; 5 Children: Nancy, Christine, Jacqueline, Paul, Alexandra

Birth Date: 03/26/1940

Birth Place: Baltimore, MD

Home City: San Francisco, CA

Religion: Catholic