Summary

Current Position: US Representative of SC District 6 since 1993

Affiliation: Democrat

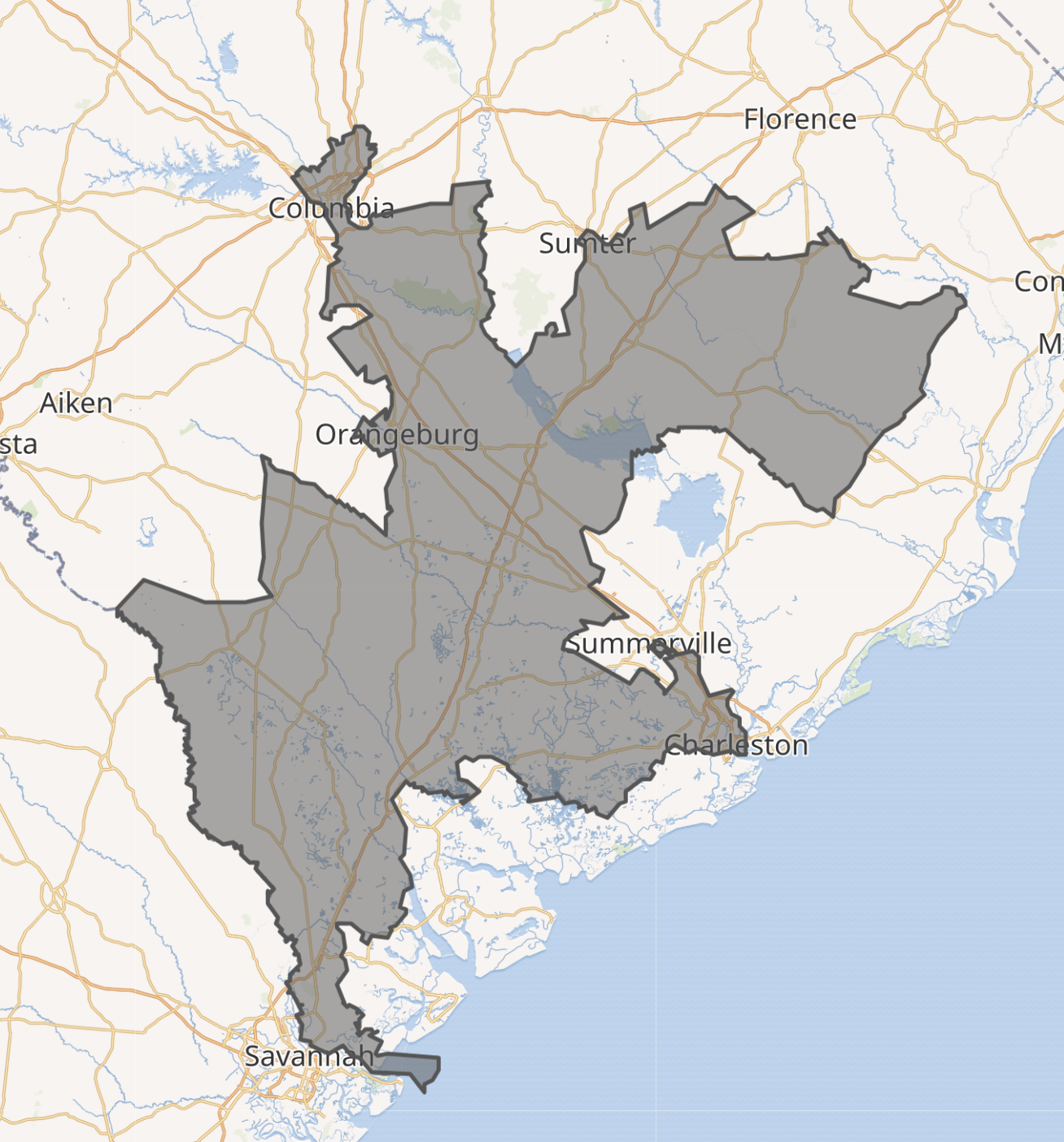

District: all of Allendale, Bamberg, Calhoun, Clarendon, Hampton, and Williamsburg counties and parts of Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Florence, Jasper, Orangeburg, Richland and Sumter counties.

Upcoming Election:

Clyburn played a pivotal role in the 2020 presidential election by endorsing Joe Biden three days before the South Carolina Democratic primary. His endorsement came at a time when Biden’s campaign had suffered three disappointing finishes in the Iowa and Nevada caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Biden’s South Carolina win three days before Super Tuesday transformed his campaign[citation needed]; the momentum led him to capture the Democratic nomination and later the presidency.

Featured Quote:

I am pleased the House passed the FY2022 Legislative Branch appropriations bill today which will remove symbols of white supremacy and hate throughout the Capitol and ensure our Congressional workforce reflects our great, diverse nation.

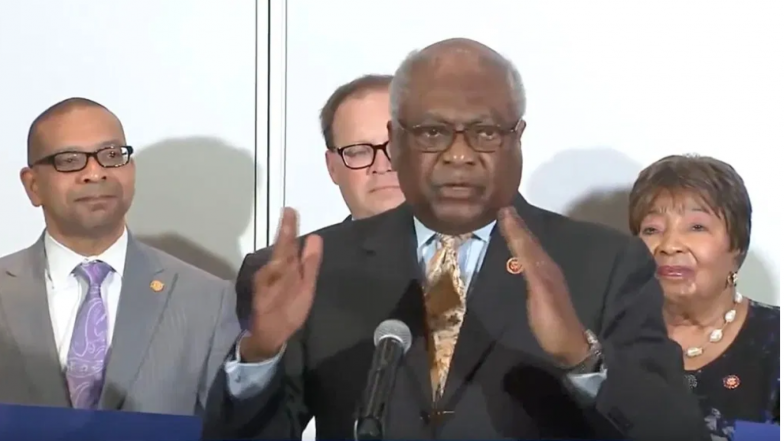

Rep. James Clyburn endorses Joe Biden ahead of South Carolina primary

OnAir Post: Jim Clyburn SC-06

News

About

Source: Government page

James E. Clyburn is the Majority Whip and the third-ranking Democrat in the United States House of Representatives. He previously served in the post from 2007 to 2011 and served as Assistant Democratic Leader from 2011 to 2019.

James E. Clyburn is the Majority Whip and the third-ranking Democrat in the United States House of Representatives. He previously served in the post from 2007 to 2011 and served as Assistant Democratic Leader from 2011 to 2019.

When he came to Congress in 1993 to represent South Carolina’s sixth congressional district, Congressman Clyburn was elected co-president of his freshman class and quickly rose through leadership ranks. He was subsequently elected Chairman of the Congressional Black Caucus, Vice Chair, and later Chair, of the House Democratic Caucus.

As a national leader, he has championed rural and economic development and many of his initiatives have become law. His 10-20-30 federal funding formula was included in four sections of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. Congressman Clyburn is also a passionate supporter of historic preservation and restoration programs. His efforts have restored scores of historic buildings and sites on the campuses of historically black colleges and universities. His legislation created the South Carolina National Heritage Corridor and the Gullah/Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor, elevated the Congaree National Monument to a National Park, and established the Reconstruction Era National Monument in South Carolina’s Lowcountry.

Congressman Clyburn’s humble beginnings in Sumter, South Carolina as the eldest son of an activist, fundamentalist minister and an independent, civic-minded beautician grounded him securely in family, faith and public service. His memoir, Blessed Experiences: Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black, was published in 2015, and has been described as a primer that should be read by every student interested in pursuing a career in public service.

Jim and his late wife, Emily England Clyburn, met as students at South Carolina State and were married for 58 years. They are the parents of three daughters; Mignon Clyburn, Jennifer Reed, and Angela Clyburn and four grandchildren.

Personal

Full Name: James ‘Jim’ E. Clyburn

Gender: Male

Family: Widowed: Emily; 3 Children: Mignon, Angela, Jennifer

Birth Date: 07/21/1940

Birth Place: Sumter, SC

Home City: Columbia, SC

Religion: African Methodist Episcopal

Source: Vote Smart

Education

BA, History, South Carolina State College, Orangeburg, 1961

Political Experience

Representative, United States House of Representatives, South Carolina, District 6, 1992-present

House Majority Whip, United States House of Representatives, 2007-2011, 2019-2023

Assistant Democratic Leader, United States House of Representatives, 2011-2019

Candidate, South Carolina Secretary of State, 1978, 1986

Professional Experience

Former Teacher, Simonton Middle School

Former Teacher, Social Studies, C.A. Brown High School

Former Executive Director, South Carolina Commission for Farm Workers

Former Minority Adviser, South Carolina Governor John West

Employment Counselor, South Carolina State Employment Security

Author, “Blessed Experiences: Genuinely Southern, Proudly Black”, 2015

Commissioner, South Carolina Human Affairs, 1974-1992

Offices

Contact

Email: Government

Web Links

Politics

Source: none

Finances

Source: Open Secrets

Committees

Chair, Congressional Black Caucus, 1999-present

Member, Congressional Asian Pacific American Caucus

Member, Congressional Human Rights Caucus

Member, Congressional Rural Caucus

Member, Congressional Travel and Tourism Caucus

Chair, House Democratic Caucus

Former Chair, House Select Subcommittee on the Coronavirus Crisis

Vice Chair, House Democratic Caucus, 2002-2006

New Legislation

Issues

Source: Government page

Legislation

More Information

Services

Source: Government page

District

Source: Wikipedia

South Carolina’s 6th congressional district is in central and eastern South Carolina. It includes all of Allendale, Bamberg, Calhoun, Clarendon, Hampton, and Williamsburg counties and parts of Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Florence, Jasper, Orangeburg, Richland and Sumter counties. With a Cook Partisan Voting Index rating of D+14, it is the only Democratic district in South Carolina.[2]

South Carolina’s 6th congressional district is in central and eastern South Carolina. It includes all of Allendale, Bamberg, Calhoun, Clarendon, Hampton, and Williamsburg counties and parts of Charleston, Colleton, Dorchester, Florence, Jasper, Orangeburg, Richland and Sumter counties. With a Cook Partisan Voting Index rating of D+14, it is the only Democratic district in South Carolina.[2]

The district’s current configuration dates from a deal struck in the early 1990s between state Republicans and Democrats in the South Carolina General Assembly to create a majority-black district. The rural counties of the historical black belt in South Carolina make up much of the district, but it sweeps south to include most of the majority-black precincts in and around Charleston, and sweeps west to include most of the majority-black precincts in and around Columbia. It also includes most of the majority black areas near Beaufort (though not Beaufort itself).

Wikipedia

Contents

James Enos Clyburn (born July 21, 1940) is an American politician serving as the U.S. representative for South Carolina’s 6th congressional district. First elected in 1992, Clyburn is in his 17th term, representing a congressional district that includes most of the majority-black precincts in and around Columbia and Charleston, as well as most of the majority-black areas outside Beaufort and nearly all of South Carolina’s share of the Black Belt. Since Joe Cunningham‘s departure in 2021, Clyburn has been the only Democrat in South Carolina’s congressional delegation and as well as the dean of this delegation since 2011 after fellow Democrat John Spratt lost re-election.

Clyburn served as the third-ranking House Democrat, behind Nancy Pelosi and Steny Hoyer, from 2007 until 2023, serving as majority whip behind Pelosi and Hoyer during periods of Democratic House control, and as assistant Democratic leader behind Pelosi and Hoyer during periods of Republican control. He was House Majority Whip from 2007 to 2011 and again from 2019 to 2023 and also House assistant Democratic leader from 2011 to 2019 and again from 2023 to 2024.[1] After the Democrats took control of the House in the 2018 midterm elections, Clyburn was reelected majority whip in January 2019 at the opening of the 116th Congress, alongside the reelected Speaker Pelosi and Majority Leader Hoyer, marking the second time the trio has served in these roles together.

In the 2022 midterm elections, Republicans gained control of the House, and Pelosi retired as leader of the House Democratic Caucus. In the 2022 United States House of Representatives Democratic Caucus leadership election, Clyburn successfully sought the position as House Assistant Democratic Leader, rather than that of Democratic Whip.[2][3]

Clyburn played a pivotal role in the 2020 presidential election by endorsing Joe Biden three days before the South Carolina Democratic primary. His endorsement came at a time when Biden’s campaign had suffered three disappointing finishes in the Iowa and Nevada caucuses and the New Hampshire primary. Biden’s South Carolina win three days before Super Tuesday transformed his campaign; the momentum led him to capture the Democratic nomination and later the presidency.

Early life and education

Clyburn was born in Sumter, South Carolina, the son of Enos Lloyd Clyburn, a fundamentalist minister, and his wife Almeta (née Dizzley), a beautician.[4][5] A distant kinsman was George W. Murray, an organizer for the Colored Farmers Alliance (CFA), who was a Republican South Carolina Congressman in the 53rd and 54th U.S. Congresses in the late 19th century.[6] He and other black politicians strongly opposed the 1895 state constitution, which essentially disenfranchised most African-American citizens, a situation the state maintained for more than half a century until federal civil rights legislation passed in the mid-1960s.

Clyburn graduated from Mather Academy (later named Boylan-Haven-Mather Academy) in Camden, South Carolina, then attended South Carolina State College (now South Carolina State University), a historically black college in Orangeburg. He joined the Omega Psi Phi fraternity and graduated with a baccalaureate in history.

In his first full-time position after college, Clyburn taught at C.A. Brown High School in Charleston, South Carolina.

Early political career

Clyburn became involved in politics during the 1969 Charleston hospital strike.[7] After assisting the settlement of the protests at the Medical University of South Carolina, he became involved in St. Julian Devine‘s campaign for a seat on the Charleston city council in 1969. Clyburn came up with the campaign’s slogan, “Devine for Ward Nine”. When Devine won the race, he became the first African American to hold a seat on the city council since Reconstruction. Clyburn later credited that campaign as the reason he got into electoral politics.[8]

After an unsuccessful run for the South Carolina General Assembly, Clyburn moved to Columbia to join the staff of Governor John C. West in 1971. West called Clyburn and offered him a job as his advisor after reading Clyburn’s response to his loss in the newspaper. After West appointed Clyburn as his advisor, Clyburn became the first nonwhite advisor to a governor in South Carolina history.

In the aftermath of the 1968 Orangeburg massacre, when police killed three protesting students at South Carolina State, West appointed Clyburn as the Commissioner of the South Carolina Human Affairs Commission.[9] He served in this position until 1992, when he stepped down to run for Congress. The Orangeburg massacre and civil-rights protest predated the 1970 Kent State shootings and 1970 Jackson State killings, in which the National Guard at Kent State, and police and state highway patrol at Jackson State, killed student protesters demonstrating against the U.S. invasion of Cambodia during the Vietnam War.[10]

U.S. House of Representatives 1993–present)

| Part of a series on |

| Modern liberalism in the United States |

|---|

|

Elections

After the 1990 census South Carolina’s district lines were redrawn. Due to prior racial discrimination before the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Supreme Court required the 6th district, which had previously included the northeastern portion of the state, to be redrawn as a black-majority district. The 6th was reconfigured to take in most of the majority-black areas near Columbia and Charleston, as well as most of the Black Belt. Five-term incumbent Robin Tallon‘s home in Florence stayed in the district, but he chose to retire. Five candidates, all of whom were African American, ran for the Democratic nomination for the seat. Clyburn’s campaign was led by NAACP activist Isaac W. Williams.[11]

Clyburn won 55% of the vote in the primary, eliminating the need for a runoff. As expected, he won the general election in November handily, becoming the first Democrat to represent a significant portion of Columbia since 1965 and the first Democrat to represent a significant portion of Charleston since 1981. He was the first African-American to represent South Carolina in Congress since George W. Murray in 1893.[12] He has been reelected 15 times with no substantive Republican opposition.

For his first 10 terms, Clyburn represented a district that stretched from the Pee Dee through most of South Carolina’s share of the Black Belt, but swept west to include most of the majority-black precincts in and around Columbia and south to include most of the majority-black precincts in and around Charleston. After the 2010 census, the district was pushed well to the south, losing its portion of the Pee Dee while picking up almost all of the majority-black precincts near Beaufort and Hilton Head Island (though not taking in any of Beaufort or Hilton Head themselves). The reconfigured 6th was no less Democratic than its predecessor. In all its incarnations as a gerrymandered black-majority district, it has been dominated by black voters in the Columbia and Charleston areas, and for much of that time has been the only safe Democratic district in the state.

In 2008, Clyburn defeated Nancy Harrelson, 68% to 32%.[13] In 2010, he defeated Jim Pratt, 65% to 34%.[14] In 2012, Clyburn defeated Anthony Culler, 73% to 25%.[15]

In March 2024, Clyburn announced his run for re-election.[16] Duke Buckner, who ran against Clyburn in 2022, defeated Justin Scott in the June Republican Primary.[17][18] Gregg Marcel Dixon, who ran against Clyburn as a Democrat in 2022,[19] switched to the United Citizens Party for his 2024 run for the seat.[20] Alliance Party candidate Joseph Oddo and Libertarian candidate Michael Simpson have also filed for the seat.[21] In November 2024, Clyburn won re-election with 59.5% of the vote.[22]

On March 12, 2026, Clyburn announced his run for re-election.[23]

Clyburn ranked number 19 on the Post and Courier Columbia’s 2025 Power List.[24]

South Carolina redistricting

In 2023, ProPublica reported that Clyburn secretly worked with South Carolina Republicans during the 2020 Congressional redistricting process to dilute the state’s Black vote.[25] The resulting Congressional map made Democrats “have virtually no shot of winning any congressional seat in South Carolina other than Clyburn’s.”[25] The NAACP, in 2022, challenged the South Carolina’s redistricting as an unconstitutional racial gerrymander, alleging that Republicans deliberately moved Black voters into Clyburn’s district to solidify Republican control over a neighboring swing district.[26] A spokesperson for Clyburn denied “any accusation that Congressman Clyburn in any way enabled or facilitated Republican gerrymandering.”[25] The NAACP case, filed as Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, was argued on October 11, 2023, in the Supreme Court and a ruling siding with the State was made in the 2024 term.[27][28][29][30]

Tenure

Party leadership

Clyburn was elected vice-chairman of the House Democratic Caucus in 2003, the caucus’s third-ranking post.[citation needed] He became chair of the House Democratic Caucus in early 2006 after caucus chair Bob Menendez was appointed to the Senate. After the Democrats won control of the House in the 2006 election, Clyburn was unanimously elected Majority Whip in the 110th Congress.[citation needed]

Clyburn would have faced a challenge from Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee chair Rahm Emanuel, but Speaker-elect Nancy Pelosi persuaded Emanuel to run for Democratic Caucus chair.[31] Clyburn was interviewed by National Public Radio‘s Morning Edition on January 12, 2007, and acknowledged the difficulty of counting votes and rallying the fractious Democratic caucus while his party held the House majority.[citation needed]

In the 2010 elections, the Democrats lost their House majority. Pelosi ran for Minority Leader in order to remain the House party leader, while Clyburn announced that he would challenge Steny Hoyer, the second-ranking House Democrat and outgoing Majority Leader, for Minority Whip. Clyburn had the support of the Congressional Black Caucus, which wanted to keep an African-American in the House leadership, while Hoyer had 35 public endorsements, including three standing committee chairs. On November 13, Pelosi announced a deal whereby Hoyer would remain Minority Whip, while a “number three” leadership position styled Assistant Leader would be created for Clyburn.[32] The exact responsibilities of Clyburn’s assistant leader office were unclear, though it was said to replace the Assistant to the Leader post previously held by Chris Van Hollen, who had attended all leadership meetings but was not in the leadership hierarchy.[33][34]

On November 28, 2018, Clyburn was elected to serve his second stint as House Majority Whip.[35][36]

- Ideology

Clyburn is regarded as liberal in his political stances, actions and votes. In 2007 the National Journal ranked him the 77th most liberal U.S. representative, with a score of 81, indicating that the conductors of this study found his voting record to be more liberal than 81% of other House members, based on their recent voting records.[37] Clyburn identifies as a progressive,[38] but thinks the Democratic Party’s more liberal wing should be “practical,” and that liberalism and conservatism have to be balanced out. Various progressives have called him “conservative” and “centrist”.[39][40]

Clyburn has established liberal stances on health care, education, organized labor and environmental conservation issues, based on his legislative actions as well as evaluations and ratings by pertinent interest groups.[41]

- Healthcare

In 2009, Clyburn introduced the Access for All Americans Act. The $26 billion sought by the Act would provide funding to quadruple the number of community health centers in the US that provide medical care to uninsured and low-income citizens.[42]

The American Public Health Association, the American Academy of Family Physicians, The Children’s Health Fund, and other health care interest groups rate Clyburn highly based on his voting record on pertinent issues. Other groups in this field, such as the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, gave Clyburn a rating of zero in 2014.[43]

Despite his opposition to partial-birth abortion, Clyburn is regarded as pro-abortion rights, as shown by his high ratings from Planned Parenthood and NARAL Pro-Choice America and low rating from the National Right to Life Committee.[44] But at the height of national polarization after the Supreme Court’s intention to overturn Roe v. Wade had been leaked, Clyburn controversially campaigned on behalf of anti-abortion incumbent Representative Henry Cuellar, who faced a pro-choice primary challenger.[45]

- Education

Clyburn has continuously sought new and additional funding for education. He has gained additional funding for special education[46] and lower interest rates on federal student loans.[47] In many sessions Clyburn has sought, sponsored and/or voted for improvements in Pell Grant funding for college loans.[48]

The National Education Association and the National Association of Elementary School Principals rate Clyburn very highly, as do other education interest groups.[49]

- Ports

Although he was criticized for a previous expenditure of 160 million dollars to expand South Carolina’s ports, Clyburn said he would continue to make funding available for further expansions. The plan is to deepen the ports to allow for larger commercial ships to arrive from the Panama Canal, which is being expanded to allow for larger ships to pass through. This is primarily because of larger commercial ships from China, and China’s extremely high demand for soybeans, which are produced in South Carolina but must be sent to larger ports for exporting. This measure will benefit South Carolina business and farmers and is thus heavily backed by these groups.[50]

- Labor

Clyburn has consistently voted for increases in minimum wage income and to restrict employer interference with labor union organization.[51]

Many national labor unions, including the AFL–CIO, the United Auto Workers, the Communication Workers Association, and the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers, give Clyburn outstanding ratings based on his voting record on issues that pertain to labor and employment.[52]

- Environment

Clyburn has opposed legislation to increase offshore drilling for oil or natural gas. Instead, he has promoted use of nuclear energy as a cheaper alternative to fossil fuels than wind and solar energy.[53] Members of the nuclear power industry have said that there is mutual respect between Clyburn and themselves.[54] Clyburn pushed for a 2010 contract to convert plutonium from old weapons into nuclear fuel.[54][55]

Organizations such as the League of Conservation Voters and Defenders of Wildlife have viewed Clyburn favorably,[56] but he angered environmentalists when he proposed building a $150 million bridge across a swampy area of Lake Marion in Calhoun County.

- Objection to the 2004 presidential election

Clyburn was one of 31 House Democrats who voted not to count Ohio’s 20 electoral votes in the 2004 presidential election.[57] George W. Bush won Ohio by 118,457 votes.[58] Without Ohio’s electoral votes, the election would have been decided by the U.S. House of Representatives, with each state having one vote in accordance with the Twelfth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

- War in Iraq

On July 31, 2007, Clyburn said in a broadcast interview that it would be a “real big problem” for the Democratic Party if General David Petraeus issued a positive report in September, as it would split the Democratic caucus on whether to continue to fund the Iraq War. While this soundbite caused some controversy, the full quote was, in reference to the 47-member Blue Dog caucus, “I think there would be enough support in that group to want to stay the course and if the Republicans were to stay united as they have been, then it would be a problem for us.”[59]

- Bill Clinton comments

Clyburn was officially neutral during the 2008 primary battle between Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, but former President Bill Clinton blamed Clyburn for Hillary’s 29-point defeat in the South Carolina primary and the two of them had a heated telephone conversation. Clyburn had voted for Obama, saying, “How could I ever look in the faces of our children and grandchildren had I not voted for Barack Obama?”[60] He negatively viewed Bill Clinton‘s remarks about Obama winning the South Carolina primary. Clinton had compared Obama’s victory to Jesse Jackson‘s win in the 1988 primary.[61] “Black people are incensed all over this”, Clyburn said. Clinton responded that the campaign “played the race card on me”, denying any racial tone in the comment.[62] Speaking to The New York Times, Clyburn said such actions could lead to a longtime division between Clinton and his once most reliable constituency. “When he was going through his impeachment problems, it was the black community that bellied up to the bar”, Clyburn said. “I think black folks feel strongly that this is a strange way for President Clinton to show his appreciation.”[61]

- Impeachments of Bill Clinton and Donald Trump

On December 19, 1998, Clyburn voted against all four articles of impeachment against President Bill Clinton. On December 18, 2019, Clyburn voted for both articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump.[63] On January 13, 2021, one week after the January 6 United States Capitol attack, Clyburn voted for the single article of impeachment against Trump.

- Israel

In January 2017, Clyburn voted against a House resolution condemning the UN Security Council Resolution 2334, which called Israeli settlement building in the occupied Palestinian territories in the West Bank a “flagrant violation” of international law and a major obstacle to peace.[64][65] He voted to provide Israel with support following October 7 attacks.[66][67]

- Homosexuality and same-sex marriage

In 1996, Clyburn voted in favor of the Defense of Marriage Act.[68] The act restricted federal recognition of marriage to the union of a man and a woman, and explicitly granted states the power not to introduce same-sex marriage and refuse to acknowledge same-sex marriages granted under the laws of other states.[69] The House Judiciary Committee had explicitly said the act was meant to “express moral disapproval of homosexuality”.[70] The act passed by an 85-vote majority in the Senate and was signed into law by President Bill Clinton.[68]

In 2012, after Obama’s public endorsement of same-sex marriage,[71] Clyburn said in an interview that he too supported same-sex marriage.[72] In the interview, he said his former disapproval was rooted in his Christian faith, but that he had since “evolved”. Clyburn called for nationwide legislation of marriage equality, opposing Obama’s state-by-state approach, saying, “if you consider this to be a civil right—and I do—I don’t think civil rights ought to be left up to a state-by-state approach”.[72]

During the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries, when considering an endorsement, Clyburn cited Pete Buttigieg‘s sexual orientation as an issue, saying it was “no question” that his sexuality would hurt his popularity and that “[he] knew a lot of people [his] age that felt that way.”[73] Clyburn added, “I’m not going to sit here and tell you otherwise, because I think everybody knows that’s an issue.”[74] In the wake of his comments, then-candidate Kamala Harris dismissed his comments as “nonsense” and “a trope” of the African American community,[75] but the Benson Strategy Group reported that “being gay was a barrier for these voters, particularly for the men who seemed uncomfortable discussing it.”[75]

Committee assignments

For the 119th Congress:[76]

Caucus memberships

- Black Maternal Health Caucus[77]

- Congressional Black Caucus[78]

- House Democratic Caucus

- United States Congressional International Conservation Caucus[79]

- Congressional Arts Caucus[80]

- Congressional Cement Caucus

- United States–China Working Group[81]

Presidential endorsements

Clyburn is considered a power broker in South Carolina.[82][83] For almost 30 years, he has hosted an annual fish fry “that every four years becomes a must-attend event for presidential hopefuls.”[84][85]

During the 2004 Democratic presidential primaries, Clyburn supported former House Minority Leader Dick Gephardt until he dropped out of the race and then supported John Kerry. Clyburn was one of the 31 who voted in the House not to count Ohio’s electoral votes in the 2004 presidential election amid a dispute over irregularities.[86]

Like other Democratic congressional leaders, Clyburn remained publicly uncommitted throughout most of the 2008 presidential primary elections. Despite being officially neutral, Clyburn voted for Obama in the South Carolina primary. Former President Bill Clinton accused Clyburn of being responsible for Hillary’s 29-point defeat in South Carolina, while Clyburn criticized Bill Clinton’s comments on race comparing Obama’s win to that of Jesse Jackson.[60][87] Clyburn endorsed Obama on June 3, immediately before the Montana and South Dakota primaries. By that time, Obama’s lead in pledged delegates was substantial enough that those two primaries could not undo it.[88][89]

Clyburn endorsed Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential campaign.[90]

Clyburn’s endorsement of Joe Biden on February 26, 2020, three days before the South Carolina primary, was considered pivotal in the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries. Several analyses have determined the endorsement changed the trajectory of the race, due to Clyburn’s influence over the state’s African-Americans, who make up the majority of its Democratic electorate. Until Clyburn’s endorsement, Biden had not won a single primary and had placed fourth, fifth, and a distant second in the Iowa, New Hampshire, and Nevada caucuses and primaries, respectively. Three days after the South Carolina primary, Biden took a delegate lead on Super Tuesday, and a month later he clinched the nomination.[91][92][93] Biden went on to win the 2020 presidential election. Clyburn’s endorsement of Biden, and subsequent political endorsements in later Democratic primaries, have given him a reputation as a political “kingmaker”.[94][95]

In 2024, amidst calls from other Democrats for Biden to withdraw from his 2024 presidential campaign, Clyburn stated his support for Biden, but also that he would back Vice President Kamala Harris as the Democratic presidential candidate if Biden were to withdraw, which eventually came to happen.[96][97]

Donald Trump

In 2024, Clyburn said he would support President Joe Biden pardoning Donald Trump for Trump’s felony indictments.[98]

Electoral history

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn | 41,415 | 56.11% | |

| Democratic | Frank Gilbert | 11,089 | 15.02% | |

| Democratic | Ken Mosely | 9,494 | 12.86% | |

| Democratic | Herbert Fielding | 9,130 | 12.37% | |

| Democratic | John Roy Harper II | 2,680 | 3.63% | |

| Total votes | 73,808 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn | 120,647 | 65.26% | |

| Republican | John Chase | 64,149 | 34.70% | |

| Write-in | 75 | 0.04% | ||

| Total votes | 184,871 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 50,476 | 85.71% | |

| Democratic | Ben Frasier | 8,419 | 14.29% | |

| Total votes | 58,895 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 88,635 | 63.80% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 50,259 | 36.18% | |

| Write-in | 29 | 0.02% | ||

| Total votes | 138,923 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 50,933 | 87.75% | |

| Democratic | Ben Frasier | 7,107 | 12.25% | |

| Total votes | 58,040 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 120,132 | 69.41% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 51,974 | 30.03% | |

| Natural Law | Savitap Joshi | 948 | 0.55% | |

| Write-in | 26 | 0.02% | ||

| Total votes | 173,080 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 32,652 | 83.07% | |

| Democratic | Mike Wilson | 6,655 | 16.93% | |

| Total votes | 39,307 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 116,507 | 72.56% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 41,421 | 25.80% | |

| Natural Law | George C. Taylor | 2,496 | 1.55% | |

| Write-in | 152 | 0.09% | ||

| Total votes | 173,080 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 138,053 | 71.76% | |

| Republican | Vince Ellison | 50,005 | 25.99% | |

| Natural Law | Dianne Nevins | 2,339 | 1.22% | |

| Libertarian | Lynwood Hines | 1,934 | 1.01% | |

| Write-in | 49 | 0.03% | ||

| Total votes | 192,380 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 34,106 | 88.79% | |

| Democratic | Ben Frasier | 4,304 | 11.21% | |

| Total votes | 38,410 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 115,855 | 66.95% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 55,490 | 32.07% | |

| Libertarian | R. Craig Augenstein | 1,662 | 0.96% | |

| Write-in | 40 | 0.02% | ||

| Total votes | 173,047 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 161,987 | 66.98% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 75,443 | 31.20% | |

| Constitution | Gary McLeod | 4,157 | 1.72% | |

| Total | Gary McLeod | 79,600 | 32.92% | |

| Write-in | 242 | 0.10% | ||

| Total votes | 241,829 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 100,213 | 64.36% | |

| Republican | Gary McLeod | 53,181 | 34.15% | |

| Green | Antonio Williams | 2,224 | 1.43% | |

| Write-in | 88 | 0.06% | ||

| Total votes | 155,706 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 193,378 | 67.48% | |

| Republican | Nancy Harrelson | 93,059 | 32.47% | |

| Write-in | 134 | 0.05% | ||

| Total votes | 286,571 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 50,138 | 90.07% | |

| Democratic | Gregory Brown | 5,527 | 9.93% | |

| Total votes | 55,665 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 125,459 | 62.86% | |

| Republican | Jim Pratt | 72,661 | 36.41% | |

| Green | Nammu Y. Muhammad | 1,389 | 0.70% | |

| Write-in | 81 | 0.04% | ||

| Total votes | 199,590 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 218,717 | 93.62% | |

| Green | Nammu Y. Muhammad | 12,920 | 5.53% | |

| Write-in | 1,978 | 0.85% | ||

| Total votes | 233,615 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 37,429 | 85.98% | |

| Democratic | Karen Smith | 6,101 | 14.02% | |

| Total votes | 43,530 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 125,747 | 72.51% | |

| Republican | Anthony Culler | 44,311 | 25.55% | |

| Libertarian | Kevin Umbaugh | 3,176 | 1.83% | |

| Write-in | 198 | 0.11% | ||

| Total votes | 173,432 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 177,947 | 70.09% | |

| Republican | Laura Sterling | 70,099 | 27.61% | |

| Libertarian | Rich Piotrowski | 3,131 | 1.23% | |

| Green | Prince Charles Mallory | 2,499 | 0.98% | |

| Write-in | 225 | 0.09% | ||

| Total votes | 253,901 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 144,765 | 70.13% | |

| Republican | Gerhard Gressmann | 58,282 | 28.23% | |

| Green | Bryan Pugh | 3,214 | 1.56% | |

| Write-in | 172 | 0.08% | ||

| Total votes | 206,433 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 197,477 | 68.18% | |

| Republican | John McCollum | 89,258 | 30.82% | |

| Constitution | Mark Hackett | 2,646 | 0.91% | |

| Write-in | 272 | 0.09% | ||

| Total votes | 289,653 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Primary election | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 48,729 | 87.90% | |

| Democratic | Michael Addison | 4,203 | 7.58% | |

| Democratic | Gregg Dixon | 2,503 | 4.52% | |

| Total votes | 55,435 | 100% | ||

| General election | ||||

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 130,923 | 62.04% | |

| Republican | Duke Buckner | 79,879 | 37.85% | |

| Write-in | 226 | 0.11% | ||

| Total votes | 211,028 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Jim Clyburn (incumbent) | 182,056 | 59.50% | |

| Republican | Duke Buckner | 112,360 | 36.72% | |

| Libertarian | Michael Simpson | 5,279 | 1.73% | |

| United Citizens | Gregg Dixon | 4,927 | 1.61% | |

| Alliance | Joseph Oddo | 1,056 | 0.35% | |

| Write-in | 299 | 0.10% | ||

| Total votes | 305,977 | 100% | ||

| Democratic hold | ||||

Personal life

Clyburn was married to librarian Emily England Clyburn from 1961 until her death in 2019.[119] They had three daughters; their eldest, Mignon Clyburn, was appointed to the Federal Communications Commission by President Barack Obama,[120] and their second daughter, Jennifer Clyburn Reed, was appointed as federal co-chair of the newly formed Southeast Crescent Regional Commission.[121] Their third daughter, Angela Clyburn, is Political Director for the South Carolina Democratic Party[122] and a member of Richland County District One School Board.[123] In 2024, Clyburn was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Joe Biden.[124]

See also

References

- ^ Lillis, Mike (February 13, 2024). “Clyburn to step out of Democratic leadership”. The Hill. Retrieved February 15, 2024.

- ^ Rogers, Alex (November 17, 2022). ““Nancy Pelosi announces she won’t run for leadership post, marking the end of an era”“. CNN. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ Smith, Nevin (November 17, 2022). ““Clyburn announces future plans, steps away from Democratic Whip in Congress”“. WIS-TV. Retrieved November 18, 2022.

- ^ “Chapter 12 | The parable of the talents – Crossing a Great Divide”. TheState.com. May 17, 2007. Retrieved August 29, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: deprecated archival service (link) - ^ Clyburn, Jim (May 29, 2003). “Dad’s Diploma: Overcoming Injustice”. The Black Commentator. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019.

- ^ “Dredge on Marszalek, ‘A Black Congressman in the Age of Jim Crow: South Carolina’s George Washington Murray’ | H-SC | H-Net”. networks.h-net.org. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- ^ “Aftermath · The Charleston Hospital Workers Movement, 1968-1969 · Lowcountry Digital History Initiative”. ldhi.library.cofc.edu. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Clyburn, James (2015). Blessed experiences : genuinely southern, proudly black. University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1611175592. OCLC 893457675.

- ^ Saxon, Wolf (March 23, 2004). “John C. West, Crusading South Carolina Governor, Dies at 81”. The New York Times. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Morrill, Jim (February 8, 2018). “50 years after 3 students died in SC civil rights protest, survivors still ask ‘Why?’“. The Charlotte Observer. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ “Williams a leader for African-Americans in the South”. The Greenville News. Retrieved January 19, 2018.

- ^ “Black-American Members by Congress”. U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ^ “South Carolina 2008 General Election Results”. November 21, 2008. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ^ “Democrat Clyburn wins 10th term in 6th District”. WMBF News. November 3, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Lavender, Paige (November 4, 2014). “Jim Clyburn Wins Midterm Election Race Against Anthony Culler In South Carolina”. HuffPost. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Williams, Lee (March 18, 2024). “Congressman Clyburn seeks reelection, emphasizes accomplishments of Biden administration”. WOLO-TV. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Kayanja, Ian (March 18, 2024). “Duke Buckner targets Clyburn’s seat in SC’s 6th Congressional District race”. WCIV-TV. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Sockol, Matthew (June 11, 2024). “Duke Buckner secures win in S.C.’s 6th Congressional District GOP primary”. WCIV. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Brown, Ann (May 13, 2022). “Can Dixon Beat Clyburn? Dr. Boyce Watkins Interviews Pro-Reparations House Candidate Gregg Marcel Dixon”. The Moguldom Nation. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ “Statement of Intention of Candidacy & Party Pledge”. South Carolina State Election Commission. March 18, 2024. Retrieved March 18, 2024.

- ^ Wilder, Anna (March 23, 2024). “Who’s running for Congress in SC? Candidates are filing, campaigning”. AOL. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

- ^ “South Carolina Sixth Congressional District Election Results”. The New York Times. November 5, 2024. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ The Hill (March 12, 2026). Watch Live: Clyburn Makes Announcement In South Carolina. Retrieved March 12, 2026 – via YouTube.

- ^ Staff, Post and Courier Columbia (December 16, 2025). “The Post and Courier Columbia’s 2025 Power List: 30 people getting stuff done in the capital city”. Post and Courier. Retrieved December 17, 2025.

- ^ a b c Thompson, Marilyn W.; Orr, Cheney (May 5, 2023). “How Rep. James Clyburn Protected His District at a Cost to Black Democrats”. ProPublica. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ “South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, The et al v. Alexander et al, No. 3:2021cv03302 – Document 397 (D.S.C. 2022)”. Justia Law. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ Talks on Alexander v SC State NAACP Amicus Briefs, case before US Supreme Court on October 11, now available online”. League of Women Voters of South Carolina. October 8, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ Montellaro, Zach (May 15, 2023). “Supreme Court to hear racial redistricting case from South Carolina”. Politico. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ “Alexander v. South Carolina Conference of the NAACP Oral Argument”. C-Span. October 11, 2023. Retrieved December 19, 2023.

- ^ “Court rules for South Carolina Republicans in dispute over congressional map”. SCOTUSblog. May 23, 2024. Retrieved January 9, 2025.

- ^ Babington, Charles; Weisman, Jonathan (November 10, 2006). “Reid, Pelosi Expected to Keep Tight Rein in Both Chambers”. The Washington Post.

- ^ Dana Bash (November 13, 2010). “Deal ends Democratic leadership fight”. CNN.

- ^ Fahrenthold, David A. “Alexis Covey-Brandt”. The Washington Post.

- ^ Kane, Paul (November 8, 2010). “House Democrats could retain leadership team”. The Washington Post.

- ^ “South Carolina’s Jim Clyburn elected House majority whip | Palmetto Politics”. postandcourier.com. November 28, 2018. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ “S.C.’s Clyburn elected to No. 3 post in U.S. House”. The State. Retrieved January 6, 2019.

- ^ “2007 Vote Ratings”. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015.

- ^ “Why South Carolina’s James Clyburn Is Endorsing Biden | FiveThirtyEight”. YouTube. February 26, 2020.

- ^ Rosen, James (December 14, 2013). “Rep. Clyburn too conservative? Signs of emerging Democratic divide”. McClatchy Washington Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ Choi, Joseph (November 8, 2020). “Clyburn responds to Ocasio-Cortez remarks: ‘I don’t get hung up on labels’“. The Hill. Retrieved July 2, 2021.

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn”. Votesmart.org. May 14, 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Clyburn bill would extend healthcare Archived April 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn: Health Issues”. Votesmart.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn: Abortion Issues”. Votesmart.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Griffiths, Brent (May 5, 2022). “Top House Democrat James Clyburn defends campaigning for Rep. Henry Cuellar, the lone anti-abortion lawmaker in his caucus”. Business Insider. Insider Inc. Retrieved July 16, 2022.

- ^ “Education Advocates Give Funding a Boost December 20, 2001”. Archived from the original on February 3, 2011.

- ^ “The Daily WhipLine April 17, 2008”. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- ^ “The Daily WhipLine, July 18, 2007″. Archived from the original on February 26, 2009.

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn: Education”. Votesmart.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ Gene Zaleski (August 8, 2012). “Clyburn says ports worth the investment”. The Times and Democrat. Retrieved August 16, 2012.

- ^ “Jim Clyburn on Jobs”. Ontheissues.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn: Labor”. Votesmart.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ “America’s Energy Future July 11, 2008”. Archived from the original on May 5, 2011.

- ^ a b Lipton, Eric (September 5, 2010). “Congressional Charities Pulling In Corporate Cash”. The New York Times. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ “Shaw AREVA MOX Services Awarded Multi-Billion Dollar Construction Option for DOE Facility”. Areva. Retrieved July 27, 2012.

- ^ “Project Vote Smart: Clyburn: Environmental Issues”. Votesmart.org. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ “Final Vote Results for Role Call 7”. Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. January 6, 2005. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Salvato, Albert (December 29, 2004). “Ohio Recount Gives a Smaller Margin to Bush – The New York Times”. The New York Times.

- ^ Balz, Dan; Cillizza, Chris (July 30, 2007). “Clyburn: Positive Report by Petraeus Could Split House Democrats on War”. The Washington Post. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ a b “Bill Clinton’s 2 a.m. Phone Call to Jim Clyburn”. US News & World Report. February 11, 2014. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Black Leader in House Denounces Bill Clinton’s Remarks New York Times April 24, 2008

- ^ Phillips, Kate (April 24, 2008), “Bill Clinton Irritated by Race-Card Questions”, The New York Times.

- ^ Panetta, Grace. “WHIP COUNT: Here’s which members of the House voted for and against impeaching Trump”. Business Insider. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Marcos, Cristina (January 5, 2017). “House votes to rebuke UN on Israeli settlement resolution”. The Hill. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ “AAI Thanks 80 Representatives For Standing Against Illegal Israeli Settlements”. Arab American Institute. Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved February 12, 2019.

- ^ Demirjian, Karoun (October 25, 2023). “House Declares Solidarity With Israel in First Legislation Under New Speaker”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives (October 25, 2023). “Roll Call 528 Roll Call 528, Bill Number: H. Res. 771, 118th Congress, 1st Session”. Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives. Retrieved October 30, 2023.

- ^ a b “H.R. 3396 (104th): Defense of Marriage Act — House Vote #316 — Jul 12, 1996”. GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ “Summary of H.R. 3396 (104th): Defense of Marriage Act”. GovTrack.us. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ “Lawmakers’ ‘moral disapproval’ of gay people in 1996 could doom DOMA law in Supreme Court”. news.yahoo.com. March 27, 2013. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Phil Gast (May 9, 2012). “Obama announces he supports same-sex marriage”. CNN Digital. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Sands, Geneva (May 14, 2012). “Clyburn splits with Obama, says gay marriage should not be left up to states”. TheHill. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Tripp, Drew (November 4, 2019). “Clyburn says Pete Buttigieg being gay is an issue for older black voters”. WCIV. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ Scott, Eugene. “Analysis | Buttigieg’s campaign says it doesn’t think homophobia is why he can’t get a foothold with black voters”. Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ a b Dugyala, Rishika (November 4, 2019). “‘Just nonsense’: Kamala Harris calls narrative that black voters are homophobic a trope”. POLITICO. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- ^ “List of Standing Committees and Select Committees of the House of Representatives” (PDF). Clerk of the United States House of Representatives. Retrieved May 13, 2025.

- ^ “Caucus Members”. Black Maternal Health Caucus. June 15, 2023. Retrieved July 16, 2025.

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Black Caucus. Retrieved March 7, 2018.

- ^ “Our Members”. U.S. House of Representatives International Conservation Caucus. Archived from the original on August 1, 2018. Retrieved August 1, 2018.

- ^ “Membership”. Congressional Arts Caucus. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- ^ “Our Mission”. U.S.-China Working Group. Retrieved February 26, 2025.

- ^ Brockel, Gillian (January 10, 2020). “A civil rights love story: The congressman who met his wife in jail in 1960”. Washington Post. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ Eichel, Henry (October 19, 2003). “Presidential candidates covet endorsement from Clyburn”. GoUpstate. Retrieved August 7, 2020.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Davis, Susan (June 14, 2019). “Why 2020 Democrats Are Lining Up For Clyburn’s ‘World Famous’ Fish Fry”. NPR. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019.

- ^ Martin, Jonathan (June 21, 2019). “Hoping to Woo Black Voters, Democratic Candidates Gather at James Clyburn’s Fish Fry”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ “Final vote results for roll call 7”. January 6, 2005. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- ^ Alexander Mooney (April 26, 2008). “Prominent black lawmaker scolds Bill Clinton”. CNN. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ Steady Stream of superdelegates pushed Obama over top CNN June 3, 2008.

- ^ Wilgoren, Debbi (June 3, 2008). “Clyburn Endorses Obama”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved May 31, 2013.

- ^ “South Carolina Rep. Jim Clyburn endorses Hillary Clinton”. USA TODAY. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- ^ “Clyburn endorsement carries considerable weight in SC: exit poll”. MSNBC. February 29, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Strauss, Daniel (March 4, 2020). “‘A chain reaction’: how one endorsement set Joe Biden’s surge in motion”. The Guardian. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Owens, Donna M. (April 1, 2020). “Jim Clyburn changed everything for Joe Biden’s campaign. He’s been a political force for a long time”. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ “Jim Clyburn changed everything for Joe Biden’s campaign. He’s been a political force for a long time”. Washington Post. April 1, 2020.

- ^ “James Clyburn tests his kingmaker reputation in democratic primaries”. The Wall Street Journal. May 21, 2022.

- ^ “Clyburn sticks with Biden after press conference: ‘I’m all in.’“. Politico. July 12, 2024.

- ^ “Clyburn says he’s for Harris ‘if Biden ain’t there’“. The Hill. June 29, 2024.

- ^ “Clyburn says he’d support Biden pardoning Trump”. The Hill. December 4, 2024.

- ^ “Annual Report 1992–1993” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission. pp. 66–67, 84.

- ^ “Annual Report 1994–1995” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission. pp. 8, 34.

- ^ “Annual Report 1995–1996” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission. pp. 21, 45.

- ^ “Annual Report 1997 & 1998” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission. pp. 28, 47.

- ^ “Annual Report 2000” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “Annual Report 2002” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission. pp. 12, 40.

- ^ “Annual Report 2004” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “Election Report 2005–2006” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “Election Report 2008” (PDF). South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2010 Primaries”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2010 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2012 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2014 Primaries”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2014 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2016 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2018 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2020 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2022 Primaries”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2022 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ “2024 General Election”. South Carolina Election Commission.

- ^ Bresnahan, John (September 19, 2019). “House Majority Whip Jim Clyburn’s wife dies at 80”. Politico. Retrieved September 19, 2019.

- ^ Schatz, Amy (April 29, 2009). “Mignon Clyburn Nominated to FCC”. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ Boyer, Dave (August 4, 2021). “Biden nominates Clyburn’s daughter to federal commission on poverty”. The Washington Times. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

- ^ “SCDP Headquarters Staff”. South Carolina Democratic Party. 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ “From the Board of School Commissioners”. Richland One School District. 2023. Retrieved October 6, 2023.

- ^ “President Biden Announces Recipients of the Presidential Medal of Freedom”. The White House. May 3, 2024. Retrieved May 3, 2024.

Further reading

- Thomas, Rhondda R. & Ashton, Susanna, eds. (2014). The South Carolina Roots of African American Thought. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. “James E. Clyburn (b. 1940),” p. 273-278.

External links

- Congressman James E. Clyburn – official U.S. House website

- Office of the Assistant Democratic Leader – official leadership website

- Jim Clyburn for Congress

- Jim Clyburn statue unveiled at Allen University on WLTX, October 27, 2023

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Financial information (federal office) at the Federal Election Commission

- Legislation sponsored at the Library of Congress

- Profile at Vote Smart

- Appearances on C-SPAN

- GOP Agenda Is a Plague on Americans by Jim Clyburn, September 24, 2010