Summary

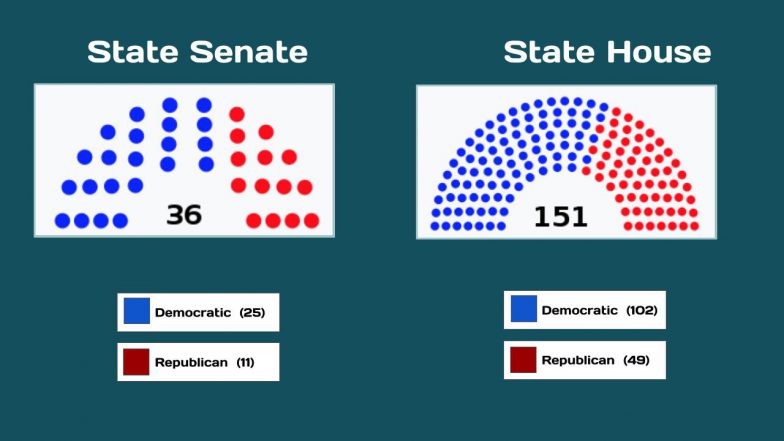

The Connecticut General Assembly (CGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is a bicameral body composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. It meets in the state capital, Hartford. There are no term limits for either chamber.

During even-numbered years, the General Assembly is in session from February to May. In odd-numbered years, when the state budget is completed, session lasts from January to June. The governor has the right to call for a special session after the end of the regular session, while the General Assembly can call for a “veto session” after the close in order to override gubernatorial vetoes.

During the first half of session, the House and Senate typically meet on Wednesdays only, though by the end of the session, they meet daily due to increased workload and deadlines.

OnAir Post: CT General Assembly

News

Bill legalizing sports betting, online casino games goes to Senate

Connecticut reached a tipping point in its long, complicated relationship with gambling Thursday as the House voted 122-21 for a bill that would make casino games, sports betting and lottery sales available to any adult with an internet connection.

After years of false starts, the measure is the first comprehensive update of gambling laws since the state’s two federally recognized tribes opened Foxwoods Resorts Casino and the Mohegan Sun in the 1990s.

It authorizes the CT Lottery and the two casinos to take sports bets and the casinos to offer virtual versions of slots and table games, a source of new revenue for casinos battered by COVID-19 and competition.

The overwhelming vote in favor reflects a cultural and political shift in a state that barred the sales of liquor on Good Friday until an adverse court ruling in 1981 and clung to Sunday blue laws into the new millennium.

Insist Lamont and lawmakers must compromise on tax reform issues

With state tax receipts booming and billions of federal pandemic relief dollars flowing into Connecticut, leaders of the legislature’s Democratic majority on Wednesday predicted swift adoption of a new state budget.

Democratic legislative leaders, who are still at odds with Gov. Ned Lamont over several proposals to shift tax burdens from the poor and middle class onto the rich, also predicted they would make progress in this area — without an adversarial showdown with the fiscally moderate-to-conservative governor.

“This budget really does a lot of things a lot of folks care about,” House Speaker Matt Ritter, D-Hartford said, referring to the biennial budget proposed by legislative committees, as well as plans to invest federal American Rescue Plan money in core services and programs. “We think we are very close to wrapping things up.”

About

Source: Wikipedia

History

The three settlements that would become Connecticut (Hartford, Wethersfield, and Windsor) were established in 1633, and were originally governed by the Massachusetts Bay Company under terms of a commission for settlement. When the commission expired in 1636 and the Connecticut Colony was established, the legislature was established as the “General Corte”, consisting of six magistrates along with three-member committees representing each of the three towns. In 1639, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut were adopted, which changed the spelling to “General Court;” formalized its executive, judicial, and legislative authority; and changed its membership to consist of the governor and six magistrates (each elected for one year terms) and three or four deputies per town (elected for six-month terms). Although the magistrates and deputies sat together, they voted separately and in 1645 it was decreed that a measure had to have the approval of both groups in order to pass. The Charter of 1662 changed the name to the General Assembly, while replacing the six magistrates with twelve assistants and reducing the number of deputies per town to no more than two. In 1698, the General Assembly divided itself into its current bicameral form, with the twelve assistants as the Council and the deputies as the House of Representatives. The modern form of the General Assembly (divided into the upper Senate and lower House and devoid of all executive and judicial authority) was incorporated in the 1818 constitution.

Facilities

Most of the General Assembly’s committee and caucus meetings are held in the modern Legislative Office Building (or LOB), while the House and Senate sessions are held in the State Capitol. The two buildings are connected via a tunnel known as the “Concourse,” which stretches underneath an off-ramp of Interstate 84. Most offices for legislators and their aides are also housed in the LOB, though some legislative leaders choose to be based in the State Capitol itself.

Each committee has its own office space, with most being located in the LOB. A few committees, particularly select committees, have their offices in the Capitol. Committee chairs and ranking members normally choose to have their personal offices near their committee offices, rather than staying in their caucus areas.

The General Assembly is also provided with facilities such as a cafeteria, private dining room, newsstand, and library.

Committee system

The General Assembly has 26 committees, all of which are joint committees; that is, their membership includes House and Senate members alike. Several committees have subcommittees, each with their own chair and special focus.

Before most bills are considered in either the House or Senate, they must first go through the committee system. The primary exception to this rule is the emergency certification bill, or “e-cert,” which can be passed on the floor without going through committee first. The e-cert is generally reserved for use during times of crisis, such as natural disasters or when deadlines are approaching too quickly to delay action.

Permanent committees

Most are permanent committees, which are authorized and required by state statute to be continued each session.

The twenty-five permanent committees of the General Assembly are:

- Aging Committee

- Appropriations Committee

- Banks Committee

- Children Committee

- Commerce Committee

- Education Committee (K-12)

- Energy and Technology Committee

- Environment Committee

- Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee

- Finance, Revenue, and Bonding Committee

- General Law Committee

- Government Administration and Elections Committee

- Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee

- Housing Committee

- Human Services Committee

- Insurance and Real Estate Committee

- Internship Committee

- Judiciary Committee

- Labor and Public Employees Committee

- Joint Committee on Legislative Management

- Planning and Development Committee

- Public Health Committee

- Public Safety and Security Committee

- Regulation Review Committee

- Transportation Committee

- Veterans’ Affairs Committee

Of those, the Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee, Internship Committee, Joint Committee on Legislative Management, and Regulation Review Committee are considered bi-partisan and feature leadership from each party.

Select committees[edit]

Some committees are select committees, authorized to only function for a set number of years before being brought up for review. Most select committees deal with issues of major importance during a particular time period and are created in response to specific problems facing the state. As of the 2013 legislative session, there are no active select committees.

Leadership and staff

Most committee chair positions are held by the ruling party, but committees considered officially bi-partisan have chairs from both the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Bi-partisan committees are ones that are mostly administrative in nature, such as the Legislative Internship Committee. Most committees have ranking members, or leaders from the minority party who serve as the leaders of their party on each committee.

All committees have their own staff members. The four largest committees (Appropriations, Finance, Judiciary, and Public Health) are led by non-partisan senior committee administrators. The rest are led by a committee clerk appointed by the majority party. The majority and minority party appoint assistant clerks.

Each committee is assigned additional non-partisan staffers from the Office of Legislative Research, the Office of Fiscal Analysis, and the Legislative Commissioners’ Office who, respectively, research legislation and issues, assess fiscal impacts, and draft legislation.

Subpoena power

The General Assembly has subpoena power under Connecticut General Statutes §2-46. Recent decisions by the Connecticut Supreme Court, the state supreme court, have clarified and limited this power.

§2-46 vests the Connecticut General Assembly with broad subpoena power. The power to compel documents and testimony is vested in the President of the Senate, Speaker of the House of Representatives, or either of the chairman of any committee (Connecticut has joint Committees, with a chairman from each house of the General Assembly). Once subpoenaed, a person refusing to comply may be fined between $100 and $1000, and imprisoned for between one month and one year.

The legislature has the power to subpoena the sitting governor of Connecticut in limited circumstances. The Connecticut Supreme Court clarified these circumstances, during the John G. Rowland impeachment, in Office of the Legislature v. The Select Committee On Inquiry, 271 Conn. 540 (2004), holding that the legislature can issue subpoenas only in conjunction with its mandate under the state constitution. Impeachment is a constitutional power of the legislature under Article IX of the Connecticut Constitution, and therefore the legislature can compel the testimony of the governor in conjunction with impeachment proceedings.

The ability of the legislature to subpoena judges of the state court has also been clarified in court. During the controversy surrounding the retirement of the chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court, William “Taco” Sullivan, the Connecticut General Assembly subpoenaed the testimony of Sullivan, who was still sitting on the Court. Sullivan challenged the subpoena in Connecticut Superior Court. The court ruled, in Sullivan v. McDonald (WL 2054052 2006), that the legislature could only subpoena a sitting Justice in an impeachment proceeding. On appeal, the entire Connecticut Supreme Court recused itself, and the argument was made before the judges of the Connecticut Appellate Court sitting as the Supreme Court. The Judiciary Committee, who issued the subpoenas, argued that they could also issue subpoenas in conjunction with their constitutional confirmation power. Sullivan voluntarily testified before a ruling was issued.

Public participation

The majority of General Assembly proceedings are open to members of the public. Public hearings are held regularly during the session for residents to be given a chance to testify on pending legislation. Viewing areas are offered in both chambers for people who would like to observe, though the floor of each chamber is generally restricted to legislators, staff members, interns, and certain members of the media collectively known as the Capitol Press Corps. Additionally, the Connecticut Network, or CT-N, broadcasts the majority of each session for viewing on television.

Members of the public are often recognized during legislative proceedings, particularly sessions of the House. Representatives and Senators can call for a “point of personal privilege” when there is no business pending on the floor, which allows them to introduce family members or residents of their districts to the rest of the membership. The entire chamber often recognizes civic and youth groups, particularly championship-winning sports teams. Some residents receive special citations from the membership as well.

See also

- Connecticut State Capitol

- Connecticut House of Representatives

- Connecticut Senate

- Connecticut Capitol Police

- List of members of the Connecticut General Assembly from Norwalk

Wikipedia

Contents

The Connecticut General Assembly (CGA) is the state legislature of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is a bicameral body composed of the 151-member House of Representatives and the 36-member Senate. It meets in the state capital, Hartford. There are no term limits for members of either chamber.

During even-numbered years, the General Assembly is in session from February to May. In odd-numbered years, when the state budget is completed, session lasts from January to June. The governor has the right to call for a special session after the end of the regular session, while the General Assembly can call for a "veto session" after the close in order to override gubernatorial vetoes.

History

The three settlements that would become Connecticut (Hartford, Wethersfield, and Windsor) were established in 1633, and were originally governed by the Massachusetts Bay Company under terms of a commission for settlement. When the commission expired in 1636 and the Connecticut Colony was established, the legislature was established as the "General Corte", consisting of six magistrates along with three-member committees representing each of the three towns. In 1639, the Fundamental Orders of Connecticut were adopted, which changed the spelling to "General Court;" formalized its executive, judicial, and legislative authority; and changed its membership to consist of the governor and six magistrates (each elected for one year terms) and three or four deputies per town (elected for six-month terms). Although the magistrates and deputies sat together, they voted separately and in 1645 it was decreed that a measure had to have the approval of both groups in order to pass. The Charter of 1662 changed the name to the General Assembly, while replacing the six magistrates with twelve assistants and reducing the number of deputies per town to no more than two. In 1698, the General Assembly divided itself into its current bicameral form, with the twelve assistants as the Council and the deputies as the House of Representatives. The modern form of the General Assembly (divided into the upper Senate and lower House and devoid of all executive and judicial authority) was incorporated in the 1818 constitution.[1]

Facilities

Most of the General Assembly's committee and caucus meetings are held in the modern Legislative Office Building (LOB), while the House and Senate sessions are held in the State Capitol. The two buildings are connected via a tunnel known as the "Concourse", which stretches underneath an off-ramp of Interstate 84. Most offices for legislators and their aides are also housed in the LOB, though some legislative leaders choose to be based in the State Capitol itself.

Each committee has its own office space, with most being located in the LOB. A few committees, particularly select committees, have their offices in the Capitol. Committee chairs and ranking members normally choose to have their personal offices near their committee offices, rather than staying in their caucus areas.

The General Assembly is also provided with facilities such as a cafeteria, private dining room, newsstand, and library.

Committee system

The General Assembly has 26 committees, all of which are joint committees; that is, their membership includes House and Senate members alike. Several committees have subcommittees, each with their own chair and special focus.

Before most bills are considered in either the House or Senate, they must first go through the committee system. The primary exception to this rule is the emergency certification bill, or "e-cert," which can be passed on the floor without going through committee first. The e-cert is generally reserved for use during times of crisis, such as natural disasters or when deadlines are approaching too quickly to delay action.

Permanent committees

Most are permanent committees, which are authorized and required by state statute to be continued each session.

The twenty-seven permanent committees of the General Assembly are:

- Aging Committee[2]

- Co-Chairs: Jan Hochadel (D-S13) and Jane Garibay (D-60)

- Vice Chairs: Patricia Billie Miller (D-S27) and Mary Fortier (D-79)

- Ranking Members: Tony Hwang (R-S28) and Mitch Bolinsky (R-106)

- Appropriations Committee[3]

- Co-Chairs: Catherine Osten (D-S19) and Toni Walker (D-93)

- Vice Chairs: Joan Hartley (D-S15), Julie Kushner (D-S24), Tammy Exum (D-19), and Corey Paris (D-145)

- Ranking Members: Heather Somers (R-S18) and Tammy Nuccio (R-53)

- Banking Committee[4]

- Co-Chairs: Jason Doucette (D-13) and Patricia Billie Miller (D-S27)

- Vice Chairs: Farley Santos (D-109) and Paul Honig (D-S8)

- Ranking Members: Tom Delnicki (R-14) and Eric Berthel (R-S32)

- Children Committee[5]

- Co-Chairs: Corey Paris (D-145) and Ceci Maher (D-S26)

- Vice Chairs: Mary Welander (D-114) and Christine Cohen (D-S12)

- Ranking Members: Anne Dauphinais (R-44) and Henri Martin (R-S31)

- Commerce Committee[6]

- Co-Chairs: Joan Hartley (D-S15) and Stephen Meskers (D-150)

- Vice Chairs: MD Rahman (D-S4) and Sarah Keitt (D-134)

- Ranking Members: Henri Martin (R-S31) and Chris Aniskovich (R-35)

- Education Committee[7] (K–12)

- Co-Chairs: Douglas McCrory (D-S2) and Jennifer Leeper (D-132)

- Vice Chairs: Gary Winfield (D-S10) and Kevin Brown (D-56)

- Ranking Members: Eric Berthel (R-S32) and Lezlye Zupkus (R-89)

- Energy and Technology Committee[8]

- Environment Committee[9]

- Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee[10]

- Finance, Revenue, and Bonding Committee[11]

- General Law Committee[12]

- Government Administration and Elections Committee[13]

- Government Oversight Committee[14]

- Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee[15]

- Housing Committee[16]

- Human Services Committee[17]

- Insurance and Real Estate Committee[18]

- Internship Committee[19]

- Judiciary Committee[20]

- Labor and Public Employees Committee[21]

- Joint Committee on Legislative Management[22]

- Planning and Development Committee[23]

- Public Health Committee[24]

- Public Safety and Security Committee[25]

- Regulation Review Committee[26]

- Transportation Committee[27]

- Veterans' Affairs Committee[28]

Of those, the Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee, Internship Committee, Joint Committee on Legislative Management, and Regulation Review Committee are considered bi-partisan and feature leadership from each party.

Select committees

Some committees are select committees, authorized to only function for a set number of years before being brought up for review. Most select committees deal with issues of major importance during a particular time period and are created in response to specific problems facing the state. As of the 2025 legislative session, there is one active select committee, the Select Committee on Special Education.[29]

Leadership and staff

Most committee chair positions are held by the ruling party, but committees considered officially bi-partisan have chairs from both the Republican and Democratic caucuses. Bi-partisan committees are ones that are mostly administrative in nature, such as the Legislative Internship Committee. Most committees have ranking members, or leaders from the minority party who serve as the leaders of their party on each committee.

All committees have their own staff members. The four largest committees (Appropriations, Finance, Judiciary, and Public Health) are led by non-partisan senior committee administrators. The rest are led by a committee clerk appointed by the majority party. The majority and minority party appoint assistant clerks.

Each committee is assigned additional non-partisan staffers from the Office of Legislative Research, the Office of Fiscal Analysis, and the Legislative Commissioners' Office who, respectively, research legislation and issues, assess fiscal impacts, and draft legislation.

Subpoena power

The General Assembly has subpoena power under Connecticut General Statutes §2-46. Recent decisions by the Connecticut Supreme Court, the state supreme court, have clarified and limited this power.

§2-46 vests the Connecticut General Assembly with broad subpoena power. The power to compel documents and testimony is vested in the President of the Senate, Speaker of the House of Representatives, or either of the chairman of any committee (Connecticut has joint Committees, with a chairman from each house of the General Assembly). Once subpoenaed, a person refusing to comply may be fined between $100 and $1000, and imprisoned for between one month and one year.

The legislature has the power to subpoena the sitting governor of Connecticut in limited circumstances. The Connecticut Supreme Court clarified these circumstances, during the John G. Rowland impeachment process, in Office of the Legislature v. The Select Committee On Inquiry, 271 Conn. 540 (2004), holding that the legislature can issue subpoenas only in conjunction with its mandate under the state constitution. Impeachment is a constitutional power of the legislature under Article IX of the Connecticut Constitution, and therefore the legislature can compel the testimony of the governor in conjunction with impeachment proceedings.

The ability of the legislature to subpoena judges of the state court has also been clarified in court. During the controversy surrounding the retirement of the chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court, William "Taco" Sullivan, the Connecticut General Assembly subpoenaed the testimony of Sullivan, who was still sitting on the Court. Sullivan challenged the subpoena in Connecticut Superior Court. The court ruled, in Sullivan v. McDonald (WL 2054052 2006), that the legislature could only subpoena a sitting Justice in an impeachment proceeding. On appeal, the entire Connecticut Supreme Court recused itself, and the argument was made before the judges of the Connecticut Appellate Court sitting as the Supreme Court. The Judiciary Committee, who issued the subpoenas, argued that they could also issue subpoenas in conjunction with their constitutional confirmation power. Sullivan voluntarily testified before a ruling was issued.

Public participation

The majority of General Assembly proceedings are open to members of the public. Public hearings are held regularly during the session for residents to be given a chance to testify on pending legislation. Viewing areas are offered in both chambers for people who would like to observe, though the floor of each chamber is generally restricted to legislators, staff members, interns, and certain members of the media collectively known as the Capitol Press Corps. Additionally, the Connecticut Network, or CT-N, broadcasts the majority of each session for viewing on television.

Members of the public are often recognized during legislative proceedings, particularly sessions of the House. Representatives and Senators can call for a "point of personal privilege" when there is no business pending on the floor, which allows them to introduce family members or residents of their districts to the rest of the membership. The entire chamber often recognizes civic and youth groups, particularly championship-winning sports teams. Some residents receive special citations from the membership as well.

See also

- Connecticut State Capitol

- Connecticut House of Representatives

- Connecticut State Senate

- Connecticut Capitol Police

- List of members of the Connecticut General Assembly from Norwalk

References

- ^ Under the Gold Dome: An Insider's Look at the Connecticut Legislature, by Judge Robert Satter. New Haven: Connecticut Conference of Municipalities, 2004, pp. 16-27.

- ^ Aging Committee

- ^ Appropriations Committee

- ^ Banks Committee

- ^ Children Committee

- ^ Commerce Committee

- ^ Education Committee

- ^ Energy and Technology Committee

- ^ Environment Committee

- ^ Executive and Legislative Nominations Committee

- ^ Finance, Revenue, and Bonding Committee

- ^ General Law Committee

- ^ Government Administration and Elections Committee

- ^ Government Oversight Committee

- ^ Higher Education and Employment Advancement Committee

- ^ Housing Committee

- ^ Human Services Committee

- ^ Insurance and Real Estate Committee

- ^ Internship Committee

- ^ Judiciary Committee

- ^ Labor and Public Employees Committee

- ^ Joint Committee on Legislative Management

- ^ Planning and Development Committee

- ^ Public Health Committee

- ^ Public Safety and Security Committee

- ^ Regulation Review Committee

- ^ Transportation Committee

- ^ Veterans' Affairs Committee

- ^ Select Committee on Special Education