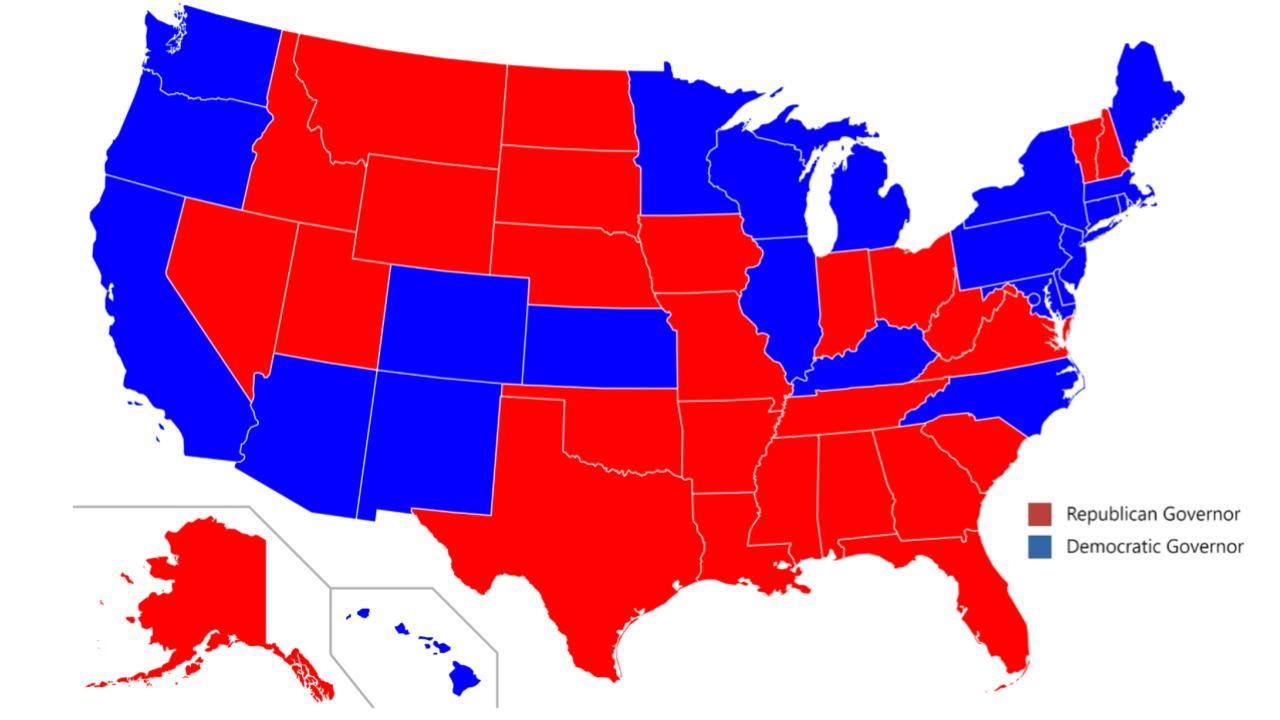

In the United States, a governor serves as the chief executive and commander-in-chief in each of the fifty states and in the five permanently inhabited territories, functioning as head of state and head of government therein.

While like all officials in the United States, checks and balances are placed on the office of the governor, significant powers may include ceremonial head of state (representing the state), executive (overseeing the state’s government), legislative (proposing, and signing or vetoing laws), judicial (granting state law pardons or commutations), and military (overseeing the militia and organized armed forces of the state). As such, governors are responsible for implementing state laws and overseeing the operation of the state executive branch. As state leaders, governors advance and pursue new and revised policies and programs using a variety of tools, among them executive orders, executive budgets, and legislative proposals and vetoes. Governors carry out their management and leadership responsibilities and objectives with the support and assistance of department and agency heads, many of whom they are empowered to appoint. A majority of governors have the authority to appoint state court judges as well, in most cases from a list of names submitted by a nominations committee.

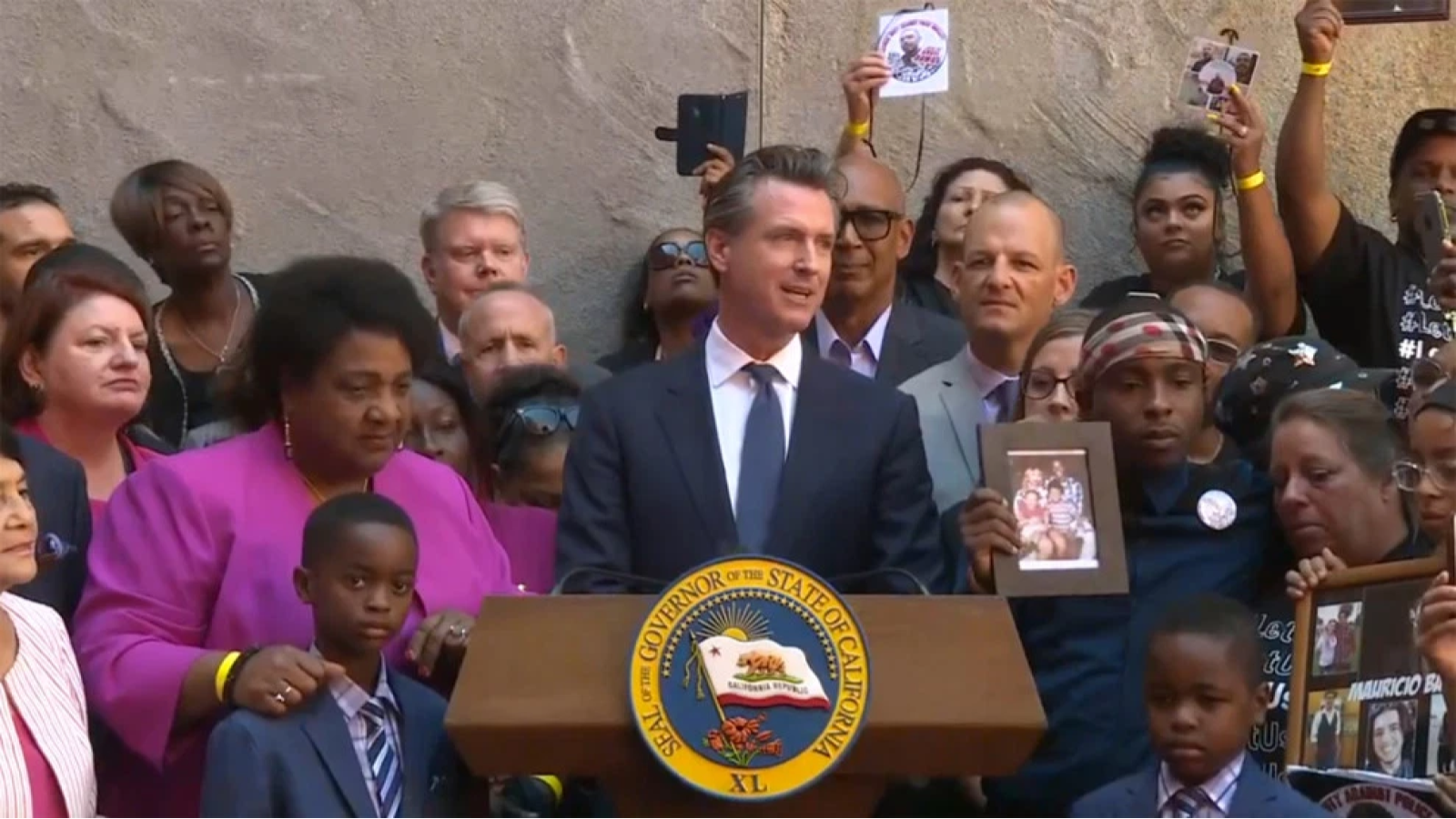

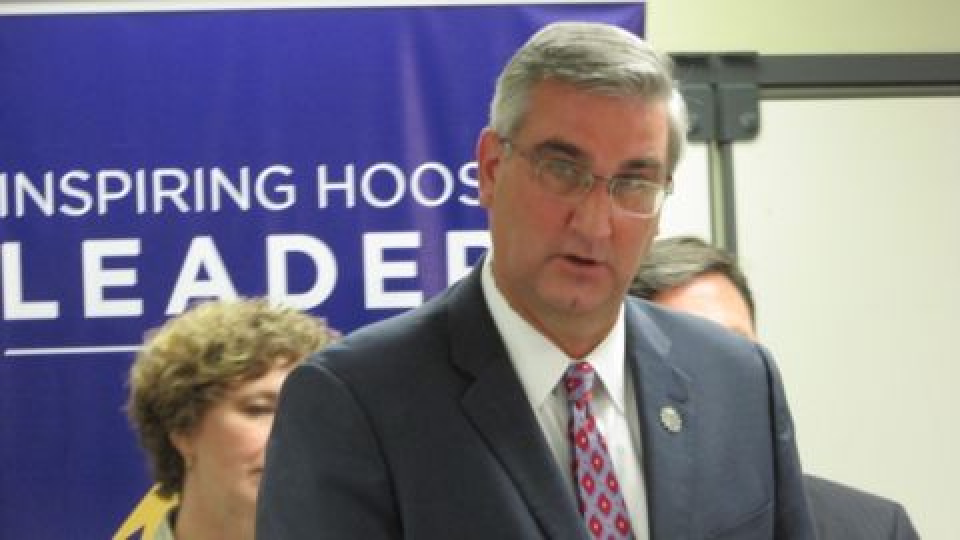

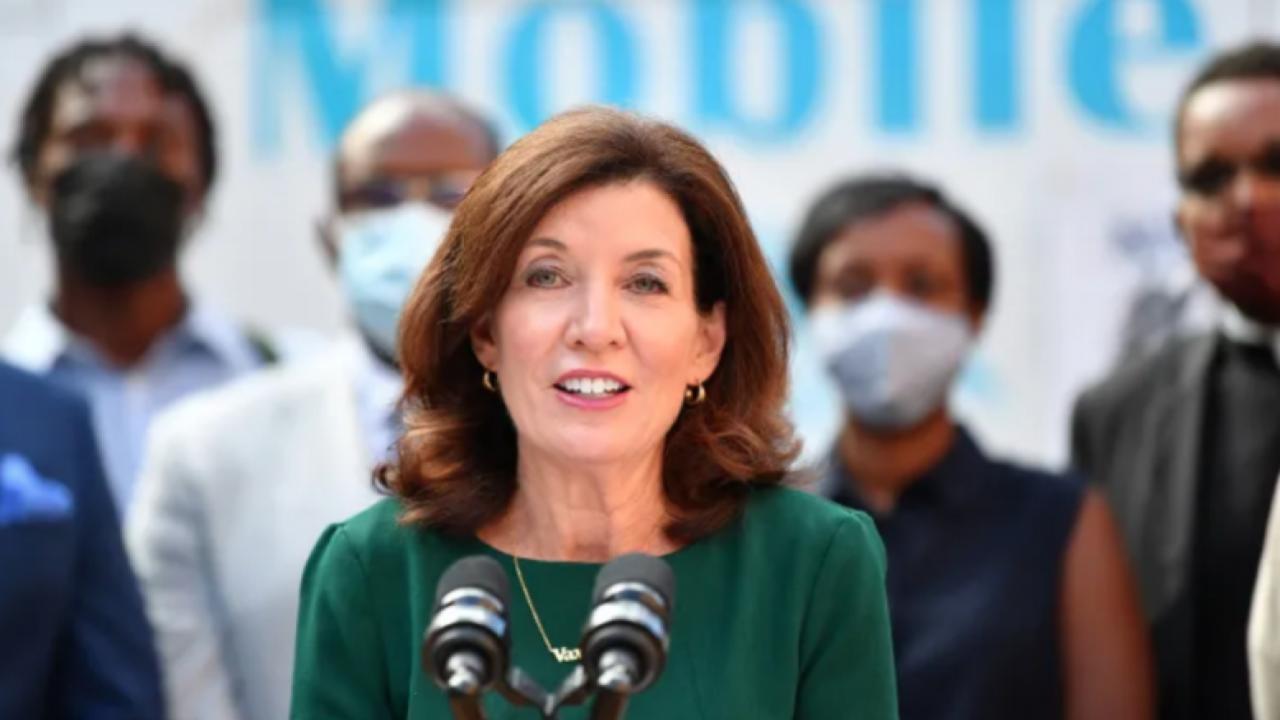

OnAir Post: 2025 Governors