Summary

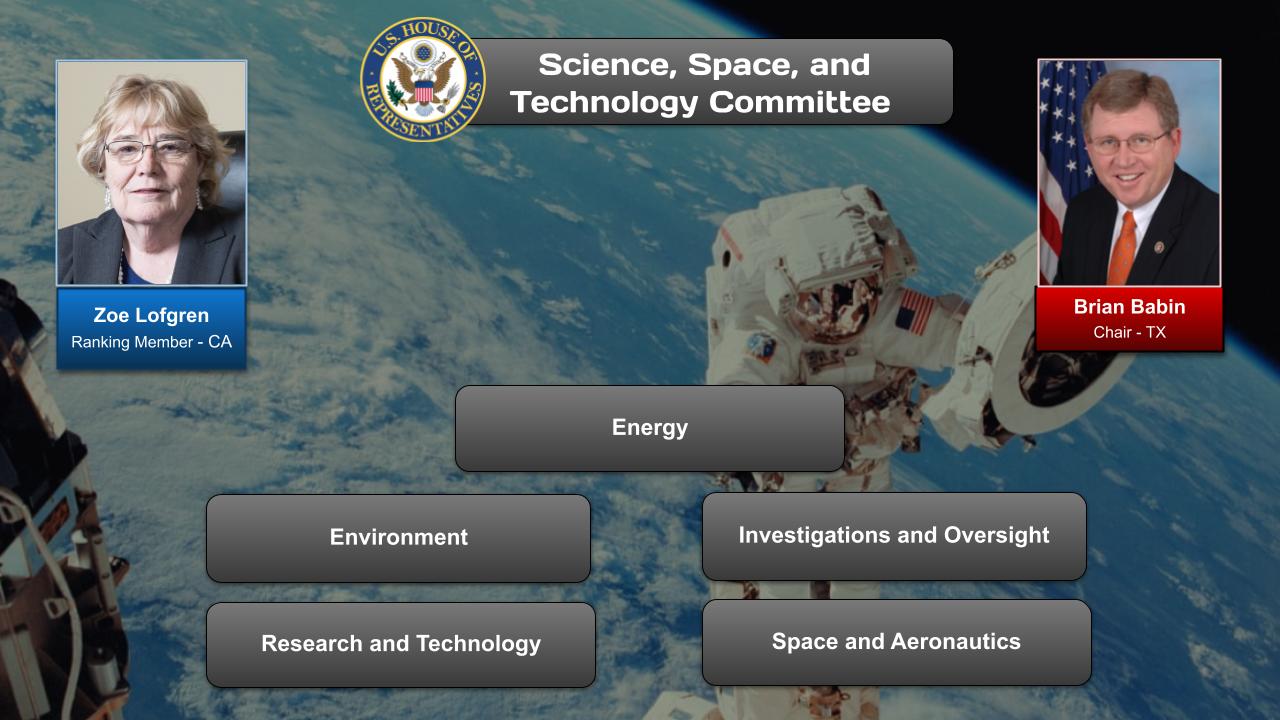

The Regulating AGI category in the US onAir hub has related posts on government agencies and departments and committees and their Chairs. In addition, the AGI Policy hub has more detailed posts on AGI regulation issues and efforts.

Note: The Trump administration is in the early phases of clarifying its policy approach to AI and AGI and many of the previous committees and legislative efforts no longer have active websites (some of the previous efforts can be found in this post).

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is a hypothetical type of intelligent agent which, if realized, could learn to accomplish any intellectual task that human beings or animals can perform. Alternatively, AGI has been defined as an autonomous system that surpasses human capabilities in the majority of economically valuable tasks. Creating AGI is a primary goal of some artificial intelligence research and of companies such as OpenAI, DeepMind, and Anthropic. AGI is a common topic in science fiction and futures studies.

- In the ‘About’ section of this post is an overview of the issues or challenges, potential solutions, and web links. Other sections have information on relevant legislation, committees, agencies, programs in addition to information on the judiciary, nonpartisan & partisan organizations, and a wikipedia entry.

- To participate in ongoing forums, ask the post’s curators questions, and make suggestions, scroll to the ‘Discuss’ section at the bottom of each post or select the “comment” icon.

Sciencephile the AI – 11/03/2023 (09:48)

OnAir Post: US AGI Policy

News

Latest

GMU (Mason News) – March 3, 2025

At last week’s Board of Visitors meeting, George Mason University’s Vice President and Chief AI Officer Amarda Shehu rolled out a new model for universities to advance a responsible approach to harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) and drive societal impact. George Mason’s model, called AI2Nexus, is building a nexus of collaboration and resources on campus, throughout the region with our vast partnerships, and across the state.

AI2Nexus is based on four key principles: “Integrating AI” to transform education, research, and operations; “Inspiring with AI” to advance higher education and learning for the future workforce; “Innovating with AI” to lead in responsible AI-enabled discovery and advancements across disciplines; and “Impacting with AI” to drive partnerships and community engagement for societal adoption and change.

Shehu said George Mason can harness its own ecosystem of AI teaching, cutting-edge research, partnerships, and incubators for entrepreneurs to establish a virtuous cycle between foundational and user-inspired AI research within ethical frameworks.

As part of this effort, the university’s AI Task Force, established by President Gregory Washington last year, has developed new guidelines to help the university navigate the rapidly evolving landscape of AI technologies, which are available at gmu.edu/ai-guidelines.

Further, Information Technology Services (ITS) will roll out the NebulaONE academic platform equipping every student, staff, and faculty member with access to hundreds of cutting-edge Generative AI models to support access, performance, and data protection at scale.

“We are anticipating that AI integration will allow us to begin to evaluate and automate some routine processes reducing administrative burdens and freeing up resources for mission-critical activities,” added Charmaine Madison, George Mason’s vice president of information services and CIO.

George Mason is already equipping students with AI skills as a leader in developing AI-ready talent ready to compete and new ideas for critical sectors like cybersecurity, public health, and government. In the classroom, the university is developing courses and curriculums to better prepare our students for a rapidly changing world.

In spring 2025, the university launched a cross-disciplinary graduate course, AI: Ethics, Policy, and Society, and in fall 2025, the university is debuting a new undergraduate course open to all students, AI4All: Understanding and Building Artificial Intelligence. A master’s in computer science and machine learning, an Ethics and AI minor for undergraduates of all majors, and a Responsible AI Graduate Certificate are more examples of Mason’s mission to innovate AI education. New academies are also in development, and the goal is to build an infrastructure of more than 100 active core AI and AI-related courses across George Mason’s colleges and programs.

The university will continue to host workshops, conferences, and public forums to shape the discourse on AI ethics and governance while forging deep and meaningful partnerships with industry, government, and community organizations to offer academies to teach and codevelop technologies to meet our global society needs. State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) will partner with the university to host an invite-only George Mason-SCHEV AI in Education Summit on May 20-21 on the Fairfax Campus.

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin has appointed Jamil N. Jaffer, the founder and executive director of the National Security Institute (NSI) at George Mason’s Antonin Scalia Law School, to the Commonwealth’s new AI Task Force, which will work with legislators to regulate rapidly advancing AI technology.

The Ezra Klein Show – March 4, 2025 (01:03:00)

Artificial general intelligence — an A.I. system that can beat humans at almost any cognitive task – is arriving in just a couple of years. That’s what people tell me — people who work in A.I. labs, researchers who follow their work, former White House officials. A lot of these people have been calling me over the last couple of months trying to convey the urgency. This is coming during President Trump’s term, they tell me. We’re not ready.

One of the people who reached out to me was Ben Buchanan, the top adviser on A.I. in the Biden White House. And I thought it would be interesting to have him on the show for a couple reasons: He’s not connected to an A.I. lab, and he was at the nerve center of policymaking on A.I. for years. So what does he see coming? What keeps him up at night? And what does he think the Trump administration needs to do to get ready for the A.G.I. – or something like A.G.I. – he believes is right on the horizon?

PBS NewsHour – October 10, 2024 (06:09)

The Nobel Prize in chemistry went to three scientists for groundbreaking work using artificial intelligence to advance biomedical and protein research. AlphaFold uses databases of protein structures and sequences to predict and even design protein structures. It speeds up a months or years-long process to mere hours or minutes. Amna Nawaz discussed more with one of the winners, Demis Hassabis.

Chemistry World, Jamie Durrani – October 9, 2024

The developers of computational tools that can be used to accurately design and predict protein structures have been recognised with this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry. The Nobel committee noted that these tools have led to a revolution in biological chemistry and are today used by millions of researchers around the world.

Demis Hassabis and John Jumper from Google’s DeepMind team received one half of the prize for their work on AlphaFold and AlphaFold2 – programs that dramatically increased the accuracy of protein structure predictions. In 2021, the team released 350,000 structures including those of all 20,000 proteins in the human proteome. In 2022 they provided the structures of a further 200 million proteins – almost every protein known to science.

The Conversation – October 10, 2024

The 2024 Nobel Prizes in physics and chemistry have given us a glimpse of the future of science. Artificial intelligence (AI) was central to the discoveries honoured by both awards. You have to wonder what Alfred Nobel, who founded the prizes, would think of it all.

We are certain to see many more Nobel medals handed to researchers who made use of AI tools. As this happens, we may find the scientific methods honoured by the Nobel committee depart from straightforward categories like “physics”, “chemistry” and “physiology or medicine”.

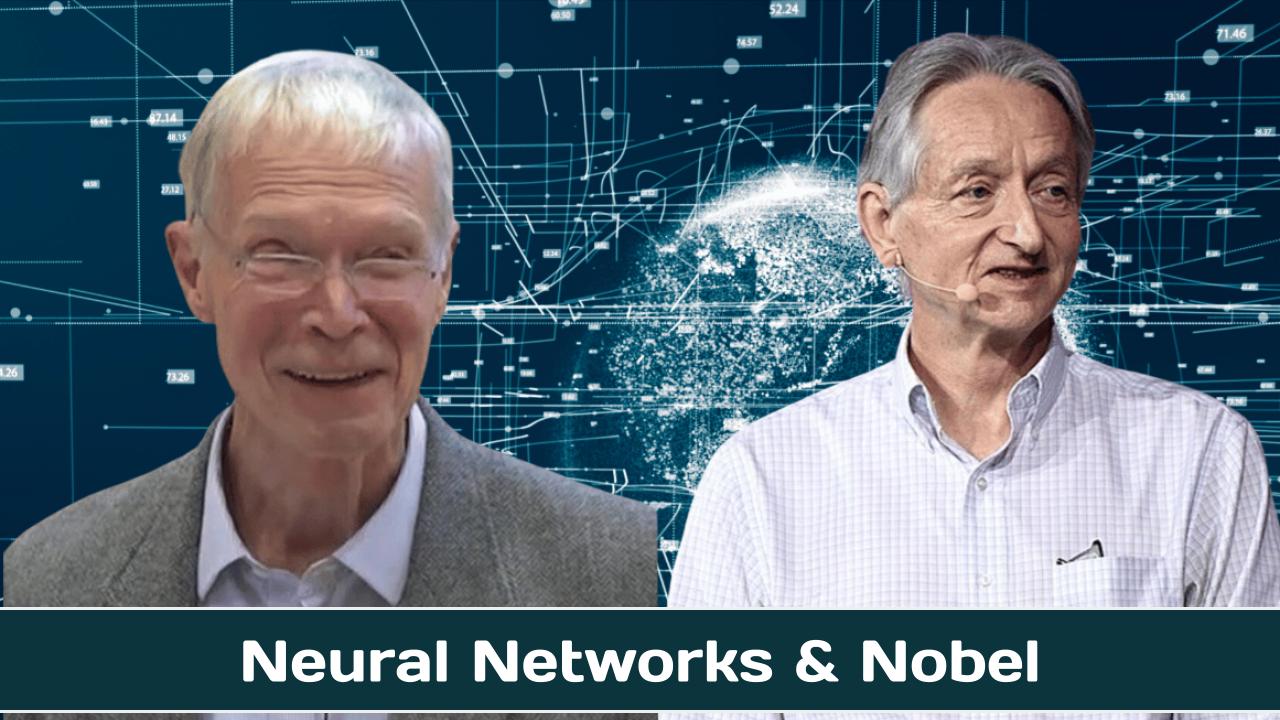

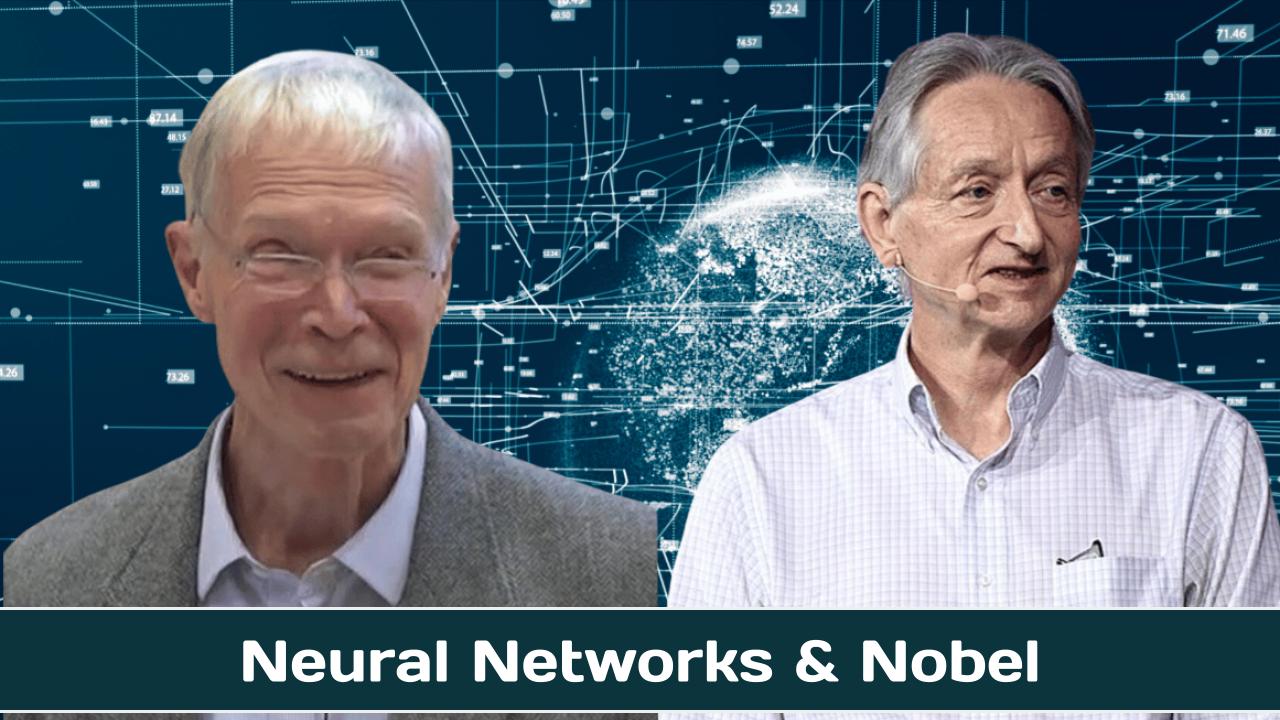

We may also see the scientific backgrounds of recipients retain a looser connection with these categories. This year’s physics prize was awarded to the American John Hopfield, at Princeton University, and British-born Geoffrey Hinton, from the University of Toronto. While Hopfield is a physicist, Hinton studied experimental psychology before gravitating to AI.

AI Upload – August 26, 2024 (27:29)

Ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently made headlines with some controversial comments about AI during an interview conduced at Stanford University. This interview was taken down at his request after he admitted to misspeaking. But did Eric Schmidt actually let on to something big coming in terms of the future of AI?

Spotlight

GMU (Mason News) – March 3, 2025

At last week’s Board of Visitors meeting, George Mason University’s Vice President and Chief AI Officer Amarda Shehu rolled out a new model for universities to advance a responsible approach to harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) and drive societal impact. George Mason’s model, called AI2Nexus, is building a nexus of collaboration and resources on campus, throughout the region with our vast partnerships, and across the state.

AI2Nexus is based on four key principles: “Integrating AI” to transform education, research, and operations; “Inspiring with AI” to advance higher education and learning for the future workforce; “Innovating with AI” to lead in responsible AI-enabled discovery and advancements across disciplines; and “Impacting with AI” to drive partnerships and community engagement for societal adoption and change.

Shehu said George Mason can harness its own ecosystem of AI teaching, cutting-edge research, partnerships, and incubators for entrepreneurs to establish a virtuous cycle between foundational and user-inspired AI research within ethical frameworks.

As part of this effort, the university’s AI Task Force, established by President Gregory Washington last year, has developed new guidelines to help the university navigate the rapidly evolving landscape of AI technologies, which are available at gmu.edu/ai-guidelines.

Further, Information Technology Services (ITS) will roll out the NebulaONE academic platform equipping every student, staff, and faculty member with access to hundreds of cutting-edge Generative AI models to support access, performance, and data protection at scale.

“We are anticipating that AI integration will allow us to begin to evaluate and automate some routine processes reducing administrative burdens and freeing up resources for mission-critical activities,” added Charmaine Madison, George Mason’s vice president of information services and CIO.

George Mason is already equipping students with AI skills as a leader in developing AI-ready talent ready to compete and new ideas for critical sectors like cybersecurity, public health, and government. In the classroom, the university is developing courses and curriculums to better prepare our students for a rapidly changing world.

In spring 2025, the university launched a cross-disciplinary graduate course, AI: Ethics, Policy, and Society, and in fall 2025, the university is debuting a new undergraduate course open to all students, AI4All: Understanding and Building Artificial Intelligence. A master’s in computer science and machine learning, an Ethics and AI minor for undergraduates of all majors, and a Responsible AI Graduate Certificate are more examples of Mason’s mission to innovate AI education. New academies are also in development, and the goal is to build an infrastructure of more than 100 active core AI and AI-related courses across George Mason’s colleges and programs.

The university will continue to host workshops, conferences, and public forums to shape the discourse on AI ethics and governance while forging deep and meaningful partnerships with industry, government, and community organizations to offer academies to teach and codevelop technologies to meet our global society needs. State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) will partner with the university to host an invite-only George Mason-SCHEV AI in Education Summit on May 20-21 on the Fairfax Campus.

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin has appointed Jamil N. Jaffer, the founder and executive director of the National Security Institute (NSI) at George Mason’s Antonin Scalia Law School, to the Commonwealth’s new AI Task Force, which will work with legislators to regulate rapidly advancing AI technology.

The Ezra Klein Show – March 4, 2025 (01:03:00)

Artificial general intelligence — an A.I. system that can beat humans at almost any cognitive task – is arriving in just a couple of years. That’s what people tell me — people who work in A.I. labs, researchers who follow their work, former White House officials. A lot of these people have been calling me over the last couple of months trying to convey the urgency. This is coming during President Trump’s term, they tell me. We’re not ready.

One of the people who reached out to me was Ben Buchanan, the top adviser on A.I. in the Biden White House. And I thought it would be interesting to have him on the show for a couple reasons: He’s not connected to an A.I. lab, and he was at the nerve center of policymaking on A.I. for years. So what does he see coming? What keeps him up at night? And what does he think the Trump administration needs to do to get ready for the A.G.I. – or something like A.G.I. – he believes is right on the horizon?

PBS NewsHour – October 10, 2024 (06:09)

The Nobel Prize in chemistry went to three scientists for groundbreaking work using artificial intelligence to advance biomedical and protein research. AlphaFold uses databases of protein structures and sequences to predict and even design protein structures. It speeds up a months or years-long process to mere hours or minutes. Amna Nawaz discussed more with one of the winners, Demis Hassabis.

The Conversation – October 10, 2024

The 2024 Nobel Prizes in physics and chemistry have given us a glimpse of the future of science. Artificial intelligence (AI) was central to the discoveries honoured by both awards. You have to wonder what Alfred Nobel, who founded the prizes, would think of it all.

We are certain to see many more Nobel medals handed to researchers who made use of AI tools. As this happens, we may find the scientific methods honoured by the Nobel committee depart from straightforward categories like “physics”, “chemistry” and “physiology or medicine”.

We may also see the scientific backgrounds of recipients retain a looser connection with these categories. This year’s physics prize was awarded to the American John Hopfield, at Princeton University, and British-born Geoffrey Hinton, from the University of Toronto. While Hopfield is a physicist, Hinton studied experimental psychology before gravitating to AI.

AI Upload – August 26, 2024 (27:29)

Ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently made headlines with some controversial comments about AI during an interview conduced at Stanford University. This interview was taken down at his request after he admitted to misspeaking. But did Eric Schmidt actually let on to something big coming in terms of the future of AI?

ReadWrite – October 9, 2024

- Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield won the Nobel Prize in Physics for AI and machine learning innovations.

- Their foundational work enables advancements in artificial neural networks and deep learning.

- Hinton expressed surprise at the award, highlighting AI’s potential to exceed human intellectual capabilities.

Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, specifically for their work on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

British-Canadian Professor Hinton is sometimes referred to as the “Godfather of AI,” while American Professor John Hopfield is a professor at Princeton University in the US. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said that the pair were jointly awarded “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

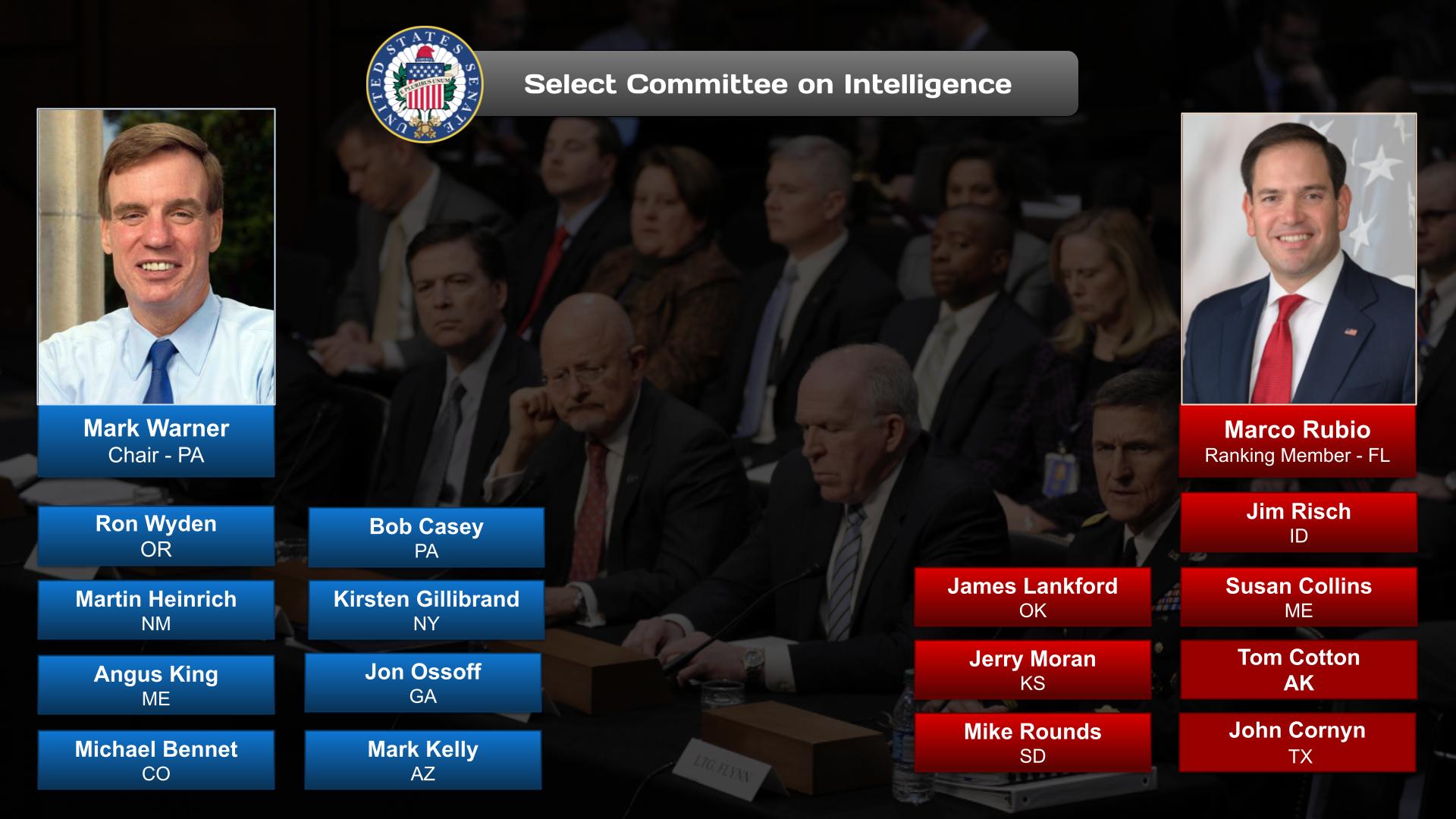

AI Supremacy Newsletter, Michael Spencer and Dean W. Ball – June 19, 2024

A closer look at the United States Senate’s AI Policy Agenda

How will the U.S. regulate AI in the long run? A bipartisan working group led by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and including Sens. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), and Todd Young (R-Ind.) released this first step on May, 17th, 2024.

According to Politico, most voters are worried about the use of AI in this year’s elections, but have mixed feelings on what to do about it. The AI Roadmap, titled “A Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Policy in the U.S. Senate,” is the culmination of extensive discussions, stakeholder meetings, and nine AI Insight Forums.

The Roadmap outlines several key objectives and policy priorities that merit bipartisan consideration in the Senate. These include:

- Increasing funding for AI innovation: To maintain global competitiveness and US leadership in AI and perform cutting-edge AI research and development

- Enforcing existing laws and addressing unintended bias: Prioritizing the development of standards for testing potential AI harms and developing use case-specific requirements for AI transparency and explainability

- Workforce considerations: Addressing the impact of AI on the workforce, including job displacement and the need for upskilling and retraining workers

- National security: Leading globally in the adoption of emerging technologies and addressing national security threats, risks, and opportunities presented by AI

- Deepfakes and content creation: Addressing challenges posed by deepfakes — media that has been digitally manipulated to replace one person’s likeness with that of another, non-consensual intimate images, and the impacts of AI on professional content creators and the journalism industry

- Data privacy: Establishing a strong comprehensive federal data privacy framework

- Mitigating long-term risks: Addressing the threat of potential long-term risk scenarios associated with AI

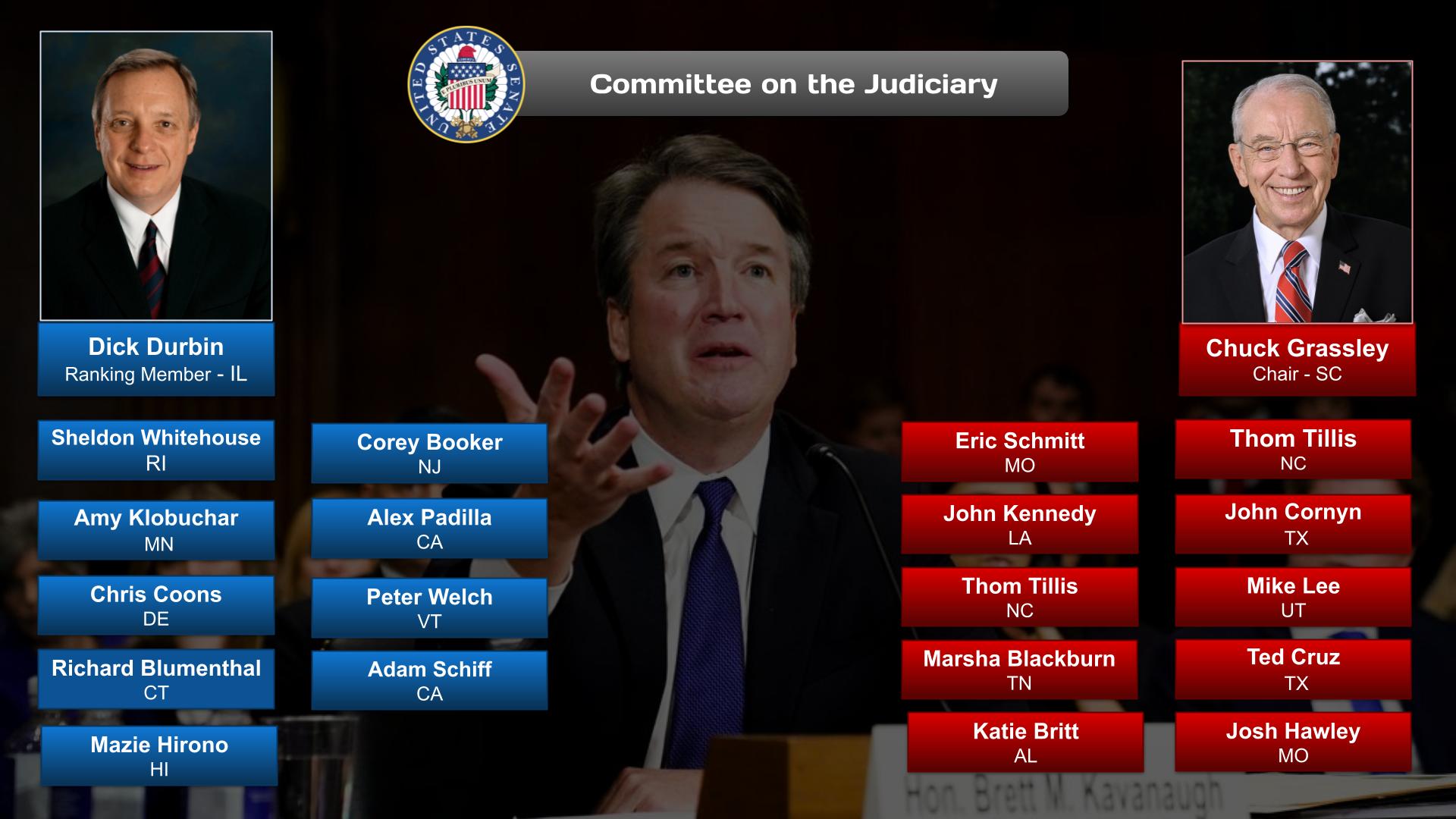

Digital Spirts, Matthew Mittelsteadt – June 19, 2024

Last week Roll Call reported “A handful of lawmakers say they plan to press the issue of the threat to humans posed by generative artificial intelligence after a recent bipartisan Senate report largely sidestepped the matter.”1 Specifically, Senators Mitt Romney (R-N.M.), Jack Reed, (D-R.I.), Jerry Moran ( R-Kan.), and Angus King, (I-Maine), joined by a handful of reps on the House side, have begun active calls for Congress to take AI risk seriously.

Trying to chart a path forward, the legislators have published a “Framework For Mitigating Extreme AI Risks.” In brief this framework proposes that developers of models trained on an “enormous amount of computing power” and are “broadly capable; general-purpose and able to complete a variety of downstream tasks; or are intended to be used for bioengineering, chemical engineering, cybersecurity, or nuclear development” must:

1. Implement so called ‘Know your customer requirements,’ that is vet, know, and report customers, especially foreign persons.

2. Notify an “oversight entity” when developing a highly capable model while also incorporating certain safeguards and cybersecurity standards into development.

3. Go through evaluation and obtain a license prior to release to try and prevent models from yielding “bioengineering, chemical engineering, cybersecurity, or nuclear development” risks. License acess would be tiered according to perceived risk levels.

The framework also proposes the creation of a new agency, or investiture of new powers in an exsisting agency or council, to implement these regulations.

Future of Life Institute, US Policy Team

On May 15, 2024, the Senate AI Working Group released “Driving U.S. Innovation in Artificial Intelligence: A Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Policy in the United States Senate,” which synthesized the findings from the Senate AI Insight Forums into a set of recommendations for Senate action moving forward. The Senate’s sustained efforts to identify and remain abreast of the key issues raised by this rapidly evolving technology are commendable, and the Roadmap demonstrates a remarkable grasp of the critical questions Congress must grapple with as AI matures and permeates our everyday lives.

The need for regulation of the highest-risk AI systems is urgent. The pace of AI advancement has been frenetic, with Big Tech locked in an out-of-control race to develop increasingly powerful, and increasingly risky, AI systems. Given the more deliberate pace of the legislative process, we remain concerned that the Roadmap’s deference to committees for the development of policy frameworks could delay the passage of substantive legislation until it is too late for effective policy intervention.

To expedite the process of enacting meaningful regulation of AI, we offer the following actionable recommendations for such policy frameworks that can form the basis of legislation to reduce risks, foster innovation, secure wellbeing, and strengthen global leadership.

DHS – April 26, 2024

Group Chaired by Secretary Mayorkas Will Consider Ways to Promote Safe and Secure Use of AI in our Nation’s Critical Infrastructure

oday, the Department of Homeland Security announced the establishment of the Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security Board (the Board). The Board will advise the Secretary, the critical infrastructure community, other private sector stakeholders, and the broader public on the safe and secure development and deployment of AI technology in our nation’s critical infrastructure. The Board will develop recommendations to help critical infrastructure stakeholders, such as transportation service providers, pipeline and power grid operators, and internet service providers, more responsibly leverage AI technologies. It will also develop recommendations to prevent and prepare for AI-related disruptions to critical services that impact national or economic security, public health, or safety.

President Biden directed Secretary Alejandro N. Mayorkas to establish the Board, which includes 22 representatives from a range of sectors, including software and hardware companies, critical infrastructure operators, public officials, the civil rights community, and academia. The inaugural members of the Board are:

- Sam Altman, CEO, OpenAI;

- Dario Amodei, CEO and Co-Founder, Anthropic;

- Ed Bastian, CEO, Delta Air Lines;

- Rumman Chowdhury, Ph.D., CEO, Humane Intelligence;

- Alexandra Reeve Givens, President and CEO, Center for Democracy and Technology

- Bruce Harrell, Mayor of Seattle, Washington; Chair, Technology and Innovation Committee, United States Conference of Mayors;

- Damon Hewitt, President and Executive Director, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law;

- Vicki Hollub, President and CEO, Occidental Petroleum;

- Jensen Huang, President and CEO, NVIDIA;

- Arvind Krishna, Chairman and CEO, IBM;

- Fei-Fei Li, Ph.D., Co-Director, Stanford Human-centered Artificial Intelligence Institute;

- Wes Moore, Governor of Maryland;

- Satya Nadella, Chairman and CEO, Microsoft;

- Shantanu Narayen, Chair and CEO, Adobe;

- Sundar Pichai, CEO, Alphabet;

- Arati Prabhakar, Ph.D., Assistant to the President for Science and Technology; Director, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy;

- Chuck Robbins, Chair and CEO, Cisco; Chair, Business Roundtable;

- Adam Selipsky, CEO, Amazon Web Services;

- Dr. Lisa Su, Chair and CEO, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD);

- Nicol Turner Lee, Ph.D., Senior Fellow and Director of the Center for Technology Innovation, Brookings Institution;

- Kathy Warden, Chair, CEO and President, Northrop Grumman; and

- Maya Wiley, President and CEO, The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

AIGRID – April 16, 2024 (29:47)

PBS NewsHour – January 1, 2024 (07:00)

As recently as the early 80s, about three of every four doctors in the U.S. worked for themselves, owning small clinics. Today, some 75 percent of physicians are employees of hospital systems or large corporate entities. Some worry the trend is leading to diminished quality of care and is one reason doctors at a large Midwestern health provider decided to unionize. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

PBS NewsHour

The race for supremacy in the age of artificial intelligence has begun. China, the USA and Europe are vying for the top spot. So are individual tech companies and start-ups. Who will determine which technologies will shape the future of humanity? The documentary follows key figures from the tech industry, science and politics who are working on artificial intelligence around the globe. They are tasked with making far-reaching decisions within a very short space of time. How can the technology’s potential be harnessed, while preventing a science fiction dystopia? The potential benefits of the currently emerging super-infrastructure are as limitless as its existential dangers. The latter include disinformation and election manipulation, as well as new forms of warfare and surveillance.

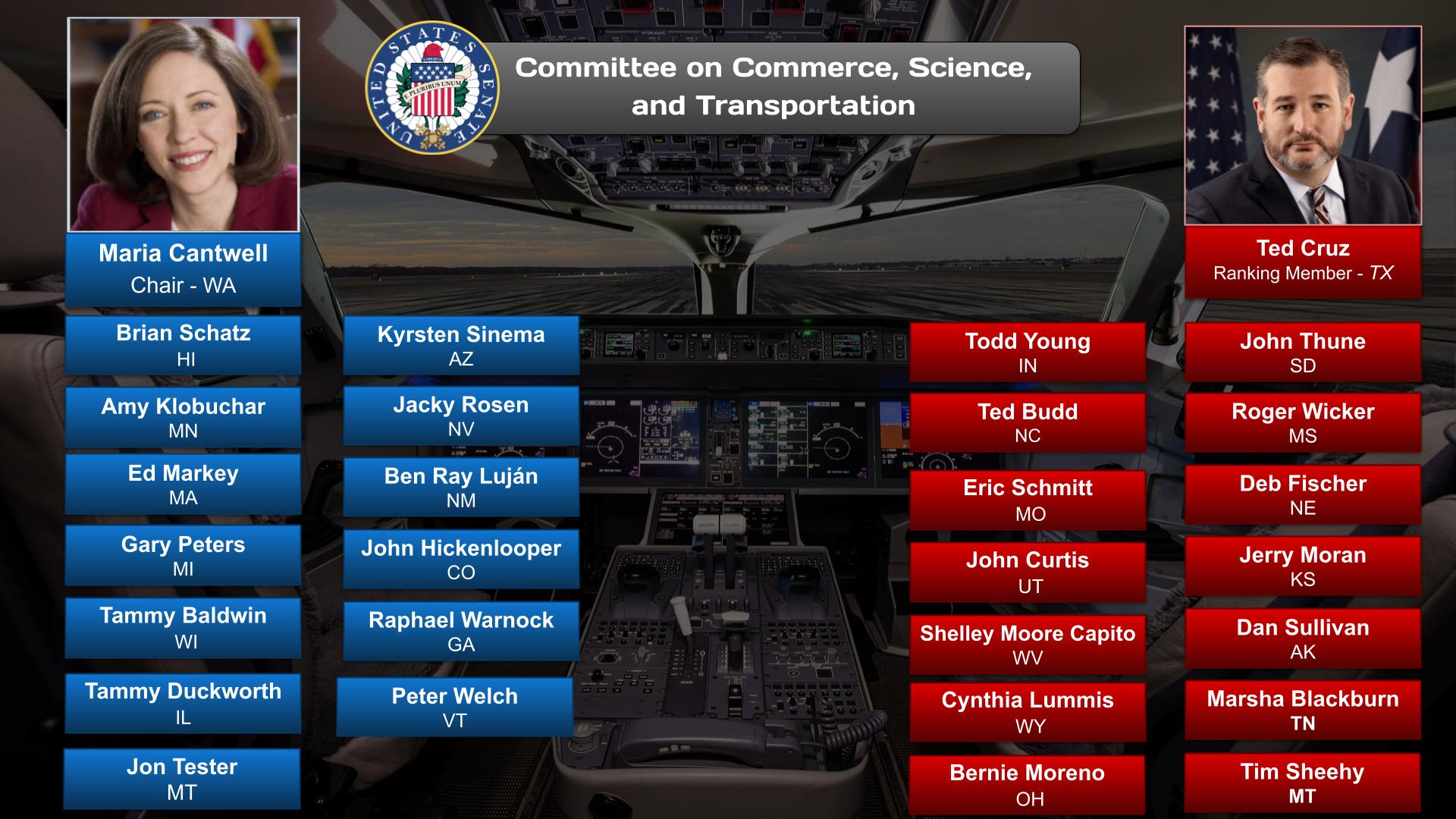

Cathy McMorris Rodgers & Maria Cantwell – April 7, 2024

The American Privacy Rights Act gives Americans fundamental, enforceable data privacy rights, puts people in control of their own data and eliminates the patchwork of state laws.

Washington, D.C. – House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation Chair Maria Cantwell (D-WA) unveiled the American Privacy Rights Act. This comprehensive draft legislation sets clear, national data privacy rights and protections for Americans, eliminates the existing patchwork of state comprehensive data privacy laws, and establishes robust enforcement mechanisms to hold violators accountable, including a private right of action for individuals.

“This bipartisan, bicameral draft legislation is the best opportunity we’ve had in decades to establish a national data privacy and security standard that gives people the right to control their personal information,” said Chair Rodgers and Cantwell. “This landmark legislation represents the sum of years of good faith efforts in both the House and Senate. It strikes a meaningful balance on issues that are critical to moving comprehensive data privacy legislation through Congress. Americans deserve the right to control their data and we’re hopeful that our colleagues in the House and Senate will join us in getting this legislation signed into law.”

“This landmark legislation gives Americans the right to control where their information goes and who can sell it. It reins in Big Tech by prohibiting them from tracking, predicting, and manipulating people’s behaviors for profit without their knowledge and consent. Americans overwhelmingly want these rights, and they are looking to us, their elected representatives, to act,” said Chair Rodgers. “I’m grateful to my colleague, Senator Cantwell, for working with me in a bipartisan manner on this important legislation and look forward to moving the bill through regular order on Energy and Commerce this month.”

“A federal data privacy law must do two things: it must make privacy a consumer right, and it must give consumers the ability to enforce that right,” said Chair Cantwell. “Working in partnership with Representative McMorris Rodgers, our bill does just that. This bipartisan agreement is the protections Americans deserve in the Information Age.”

The American Privacy Rights Act:

Establishes Foundational Uniform National Data Privacy Rights for Americans:

- Puts people in control of their own personal data.

- Eliminates the patchwork of state laws by setting one national privacy standard, stronger than any state.

- Minimizes the data that companies can collect, keep, and use about people, of any age, to what companies actually need to provide them products and services.

- Gives Americans control over where their personal information goes, including the ability to prevent the transfer or selling of their data. The bill also allows individuals to opt out of data processing if a company changes its privacy policy.

- Provides stricter protections for sensitive data by requiring affirmative express consent before sensitive data can be transferred to a third party.

- Requires companies to let people access, correct, delete, and export their data.

- Allows individuals to opt out of targeted advertising.

Gives Americans the Ability to Enforce Their Data Privacy Rights:

- Gives individuals the right to sue bad actors who violate their privacy rights—and recover money for damages when they’ve been harmed.

- Prevents companies from enforcing mandatory arbitration in cases of substantial privacy harm.

Protects Americans’ Civil Rights:

- Stops companies from using people’s personal information to discriminate against them.

- Allows individuals to opt out of a company’s use of algorithms to make decisions about housing, employment, healthcare, credit opportunities, education, insurance, or access to places of public accommodation.

- Requires annual reviews of algorithms to ensure they do not put individuals, including our youth, at risk of harm, including discrimination.

Holds Companies Accountable and Establishes Strong Data Security Obligations:

- Mandates strong data security standards that will prevent data from being hacked or stolen. This limits the chances for identity theft and harm.

- Makes executives take responsibility for ensuring that companies take all actions necessary to protect customer data as required by the law.

- Ensures individuals know when their data has been transferred to foreign adversaries.

- Authorizes the Federal Trade Commission, States, and consumers to enforce against violations.

Focuses on the Business of Data, Not Mainstreet Business

- Small businesses, that are not selling their customers’ personal information, are exempt from the requirements of this bill.

CLICK HERE to read the American Privacy Rights Act discussion draft.

CLICK HERE to read the section-by-section of the discussion draft.

CNN, Rizwan Virk – April 9, 2024

In the 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” audiences found themselves staring at one of the first modern depictions of an extremely polite but uncooperative artificial intelligence system, a character named HAL. Given a direct request by the sole surviving astronaut to let him back in the spaceship, HAL responds: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Recently, some users found themselves with a similarly (though less dramatic) polite refusal from Gemini, an integrated chatbot and AI assistant that Google rolled out as a competitor to OpenAI’s ChatGPT. When asked, Gemini politely refused in some instances to generate images of historically White people, such as the Vikings.

Unlike the fictional HAL, Google’s Gemini at least offered some explanation, saying that only showing images of White persons would reinforce “harmful stereotypes and generalizations about people based on their race,” according to Fox News Digital.

The situation quickly erupted, with some critics dubbing it a “woke” AI scandal. It didn’t help when users discovered that Gemini was creating diverse but historically inaccurate images. When prompted to depict America’s Founding Fathers, for example, it generated an image of a Black man. It also depicted a brown woman as the Pope, and various people of color, including a Black man, in Nazi uniforms when asked to depict a 1943 German soldier.

Zachary Roth – April 1, 2024

Virginia legislature considered at least 24 AI-related bills, resolutions in the 2024 session

This year’s presidential election will be the first since generative AI — a form of artificial intelligence that can create new content, including images, audio and video — became widely available. That’s raising fears that millions of voters could be deceived by a barrage of political deepfakes.

But, while Congress has done little to address the issue, states are moving aggressively to respond — though questions remain about how effective any new measures to combat AI-created disinformation will be.

Most of the bills require that creators add a disclaimer to any AI-generated content, noting the use of AI, as the NewDEAL Forum report recommends.

White House

Three months ago, President Biden issued a landmark Executive Order to ensure that America leads the way in seizing the promise and managing the risks of artificial intelligence (AI). The Order directed sweeping action to strengthen AI safety and security, protect Americans’ privacy, advance equity and civil rights, stand up for consumers and workers, promote innovation and competition, advance American leadership around the world, and more.

Today, Deputy Chief of Staff Bruce Reed will convene the White House AI Council, consisting of top officials from a wide range of federal departments and agencies. Agencies reported that they have completed all of the 90-day actions tasked by the E.O. and advanced other vital directives that the Order tasked over a longer timeframe.

Taken together, these activities mark substantial progress in achieving the EO’s mandate to protect Americans from the potential risks of AI systems while catalyzing innovation in AI and beyond. Visit ai.gov to learn more.

Managing Risks to Safety and Security

The Executive Order directed a sweeping range of actions within 90 days to address some of AI’s biggest threats to safety and security. These included setting key disclosure requirements for developers of the most powerful systems, assessing AI’s risks for critical infrastructure, and hindering foreign actors’ efforts to develop AI for harmful purposes. To mitigate these and other risks, agencies have:

- Used Defense Production Act authorities to compel developers of the most powerful AI systems to report vital information, especially AI safety test results, to the Department of Commerce. These companies now must share this information on the most powerful AI systems, and they must likewise report large computing clusters able to train these systems.

- Proposed a draft rule that proposes to compel U.S. cloud companies that provide computing power for foreign AI training to report that they are doing so. The Department of Commerce’s proposal would, if finalized as proposed, require cloud providers to alert the government when foreign clients train the most powerful models, which could be used for malign activity.

- Completed risk assessments covering AI’s use in every critical infrastructure sector. Nine agencies—including the Department of Defense, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Treasury, and Department of Health and Human Services—submitted their risk assessments to the Department of Homeland Security. These assessments, which will be the basis for continued federal action, ensure that the United States is ahead of the curve in integrating AI safely into vital aspects of society, such as the electric grid.

Innovating AI for Good

To seize AI’s enormous promise and deepen the U.S. lead in AI innovation, President Biden’s Executive Order directed increased investment in AI innovation and new efforts to attract and train workers with AI expertise. Over the past 90 days, agencies have:

- Launched a pilot of the National AI Research Resource—catalyzing broad-based innovation, competition, and more equitable access to AI research. The pilot, managed by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), is the first step toward a national infrastructure for delivering computing power, data, software, access to open and proprietary AI models, and other AI training resources to researchers and students. These resources come from 11 federal-agency partners and more than 25 private sector, nonprofit, and philanthropic partners.

- Launched an AI Talent Surge to accelerate hiring AI professionals across the federal government, including through a large-scale hiring action for data scientists. TheAI and Tech Talent Task Force created by President Biden’s E.O. has spearheaded this hiring action and is coordinating other key initiatives to facilitate hiring AI talent. The Office of Personnel Management has granted flexible hiring authorities for federal agencies to hire AI talent, including direct hire authorities and excepted service authorities. Government-wide tech talent programs, including the Presidential Innovation Fellows, U.S. Digital Corps, and U.S. Digital Service, have scaled up hiring for AI talent in 2024 across high-priority AI projects. More information about the AI Talent Surge is available at ai.gov/apply.

- Began the EducateAI initiative to help fund educators creating high-quality, inclusive AI educational opportunities at the K-12 through undergraduate levels. The initiative’s launch helps fulfill the Executive Order’s charge for NSF to prioritize AI-related workforce development—essential for advancing future AI innovation and ensuring that all Americans can benefit from the opportunities that AI creates.

- Announced the funding of new Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines), including with a focus on advancing AI. For example, with an initial investment of $15 million over two years and up to $160 million over the next decade, the Piedmont Triad Regenerative Medicine Engine will tap the world’s largest regenerative medicine cluster to create and scale breakthrough clinical therapies, including by leveraging AI. The announcement supports the Executive Order’s directive for NSF to fund and launch AI-focused NSF Engines within 150 days.

- Established an AI Task Force at the Department of Health and Human Services to develop policies to provide regulatory clarity and catalyze AI innovation in health care. The Task Force will, for example, develop methods of evaluating AI-enabled tools and frameworks for AI’s use to advance drug development, bolster public health, and improve health care delivery. Already, the Task Force coordinated work to publish guiding principles for addressing racial biases in healthcare algorithms.

The table below summarizes many of the activities federal agencies have completed in response to the Executive Order.

AI.Gov

The United States stands to benefit significantly from harnessing the opportunities of AI to improve government services. The federal government is leveraging AI to better serve the public across a wide array of use cases, including in healthcare, transportation, the environment, and benefits delivery. The federal government is also establishing strong guardrails to ensure its use of AI keeps people safe and doesn’t violate their rights.

Articles

GMU (Mason News) – March 3, 2025

At last week’s Board of Visitors meeting, George Mason University’s Vice President and Chief AI Officer Amarda Shehu rolled out a new model for universities to advance a responsible approach to harnessing artificial intelligence (AI) and drive societal impact. George Mason’s model, called AI2Nexus, is building a nexus of collaboration and resources on campus, throughout the region with our vast partnerships, and across the state.

AI2Nexus is based on four key principles: “Integrating AI” to transform education, research, and operations; “Inspiring with AI” to advance higher education and learning for the future workforce; “Innovating with AI” to lead in responsible AI-enabled discovery and advancements across disciplines; and “Impacting with AI” to drive partnerships and community engagement for societal adoption and change.

Shehu said George Mason can harness its own ecosystem of AI teaching, cutting-edge research, partnerships, and incubators for entrepreneurs to establish a virtuous cycle between foundational and user-inspired AI research within ethical frameworks.

As part of this effort, the university’s AI Task Force, established by President Gregory Washington last year, has developed new guidelines to help the university navigate the rapidly evolving landscape of AI technologies, which are available at gmu.edu/ai-guidelines.

Further, Information Technology Services (ITS) will roll out the NebulaONE academic platform equipping every student, staff, and faculty member with access to hundreds of cutting-edge Generative AI models to support access, performance, and data protection at scale.

“We are anticipating that AI integration will allow us to begin to evaluate and automate some routine processes reducing administrative burdens and freeing up resources for mission-critical activities,” added Charmaine Madison, George Mason’s vice president of information services and CIO.

George Mason is already equipping students with AI skills as a leader in developing AI-ready talent ready to compete and new ideas for critical sectors like cybersecurity, public health, and government. In the classroom, the university is developing courses and curriculums to better prepare our students for a rapidly changing world.

In spring 2025, the university launched a cross-disciplinary graduate course, AI: Ethics, Policy, and Society, and in fall 2025, the university is debuting a new undergraduate course open to all students, AI4All: Understanding and Building Artificial Intelligence. A master’s in computer science and machine learning, an Ethics and AI minor for undergraduates of all majors, and a Responsible AI Graduate Certificate are more examples of Mason’s mission to innovate AI education. New academies are also in development, and the goal is to build an infrastructure of more than 100 active core AI and AI-related courses across George Mason’s colleges and programs.

The university will continue to host workshops, conferences, and public forums to shape the discourse on AI ethics and governance while forging deep and meaningful partnerships with industry, government, and community organizations to offer academies to teach and codevelop technologies to meet our global society needs. State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) will partner with the university to host an invite-only George Mason-SCHEV AI in Education Summit on May 20-21 on the Fairfax Campus.

Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin has appointed Jamil N. Jaffer, the founder and executive director of the National Security Institute (NSI) at George Mason’s Antonin Scalia Law School, to the Commonwealth’s new AI Task Force, which will work with legislators to regulate rapidly advancing AI technology.

Chemistry World, Jamie Durrani – October 9, 2024

The developers of computational tools that can be used to accurately design and predict protein structures have been recognised with this year’s Nobel prize in chemistry. The Nobel committee noted that these tools have led to a revolution in biological chemistry and are today used by millions of researchers around the world.

Demis Hassabis and John Jumper from Google’s DeepMind team received one half of the prize for their work on AlphaFold and AlphaFold2 – programs that dramatically increased the accuracy of protein structure predictions. In 2021, the team released 350,000 structures including those of all 20,000 proteins in the human proteome. In 2022 they provided the structures of a further 200 million proteins – almost every protein known to science.

The Conversation – October 10, 2024

The 2024 Nobel Prizes in physics and chemistry have given us a glimpse of the future of science. Artificial intelligence (AI) was central to the discoveries honoured by both awards. You have to wonder what Alfred Nobel, who founded the prizes, would think of it all.

We are certain to see many more Nobel medals handed to researchers who made use of AI tools. As this happens, we may find the scientific methods honoured by the Nobel committee depart from straightforward categories like “physics”, “chemistry” and “physiology or medicine”.

We may also see the scientific backgrounds of recipients retain a looser connection with these categories. This year’s physics prize was awarded to the American John Hopfield, at Princeton University, and British-born Geoffrey Hinton, from the University of Toronto. While Hopfield is a physicist, Hinton studied experimental psychology before gravitating to AI.

ReadWrite – October 9, 2024

- Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield won the Nobel Prize in Physics for AI and machine learning innovations.

- Their foundational work enables advancements in artificial neural networks and deep learning.

- Hinton expressed surprise at the award, highlighting AI’s potential to exceed human intellectual capabilities.

Geoffrey Hinton and John Hopfield have been awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, specifically for their work on artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning.

British-Canadian Professor Hinton is sometimes referred to as the “Godfather of AI,” while American Professor John Hopfield is a professor at Princeton University in the US. The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences said that the pair were jointly awarded “for foundational discoveries and inventions that enable machine learning with artificial neural networks.”

Politico, Derek Robertson – October 11, 2024

What could the government be doing regarding technology that it isn’t?

Trying to understand it more, by ensuring they actively learn before trying to figure out how it fits into their policy worldview. AI policy is a good place to start, where the focus as soon as it was seen as important was to try and create laws and regulations as quickly as possible. Interest groups flocked in and destroyed any semblance of amity.

What’s one underrated big idea?

Almost everything in the world is downstream of strong talent selection, and our methods of selecting talent are getting worse as we try to do it even harder. Tests that used to work, work less well now. Ranks are gamed. Interviewing is hard. Even proof of work is getting gamed. Getting into a college, or a job, is impossibly hard unless you jump through hundreds of hoops.

What’s a technology that you think is overhyped?

Crypto.

Hyperdimensional, Dean W. Ball – September 26, 2024

Thoughts on the OpenAI departures and restructuring

The OpenAI drama this week is twofold: first, several key OpenAI executives—Chief Technology Officer Mira Murati, VP of Post-Training Research Barret Zoph, and Chief Research Officer Bob McGrew. Second, multiple outlets are reporting that OpenAI intends to restructure itself as a for-profit Public Benefit Corporation, with CEO Sam Altman taking an equity stake in the new company (up until now, Altman had not taken any equity in OpenAI).

Every time there is OpenAI-related drama, the safety community cynically seizes the narrative. The decision to re-structure as a Public Benefit Corporation is, we are told, the “mask coming off,” even though the PBC is precisely the same structure that OpenAI rival Anthropic employs. “This is the strongest closing argument I can imagine on the need for [SB 1047],” wrote Zvi Mowshowitz. While Zvi does not directly imply that the departures are related to the restructuring, others do; the general sense I get from scanning X is that surely, these executives left because of internal struggles related to the restructuring.

AI Supremacy Newsletter, Michael Spencer and Dean W. Ball – June 19, 2024

A closer look at the United States Senate’s AI Policy Agenda

How will the U.S. regulate AI in the long run? A bipartisan working group led by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) and including Sens. Martin Heinrich (D-N.M.), Mike Rounds (R-S.D.), and Todd Young (R-Ind.) released this first step on May, 17th, 2024.

According to Politico, most voters are worried about the use of AI in this year’s elections, but have mixed feelings on what to do about it. The AI Roadmap, titled “A Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Policy in the U.S. Senate,” is the culmination of extensive discussions, stakeholder meetings, and nine AI Insight Forums.

The Roadmap outlines several key objectives and policy priorities that merit bipartisan consideration in the Senate. These include:

- Increasing funding for AI innovation: To maintain global competitiveness and US leadership in AI and perform cutting-edge AI research and development

- Enforcing existing laws and addressing unintended bias: Prioritizing the development of standards for testing potential AI harms and developing use case-specific requirements for AI transparency and explainability

- Workforce considerations: Addressing the impact of AI on the workforce, including job displacement and the need for upskilling and retraining workers

- National security: Leading globally in the adoption of emerging technologies and addressing national security threats, risks, and opportunities presented by AI

- Deepfakes and content creation: Addressing challenges posed by deepfakes — media that has been digitally manipulated to replace one person’s likeness with that of another, non-consensual intimate images, and the impacts of AI on professional content creators and the journalism industry

- Data privacy: Establishing a strong comprehensive federal data privacy framework

- Mitigating long-term risks: Addressing the threat of potential long-term risk scenarios associated with AI

Digital Spirts, Matthew Mittelsteadt – June 19, 2024

Last week Roll Call reported “A handful of lawmakers say they plan to press the issue of the threat to humans posed by generative artificial intelligence after a recent bipartisan Senate report largely sidestepped the matter.”1 Specifically, Senators Mitt Romney (R-N.M.), Jack Reed, (D-R.I.), Jerry Moran ( R-Kan.), and Angus King, (I-Maine), joined by a handful of reps on the House side, have begun active calls for Congress to take AI risk seriously.

Trying to chart a path forward, the legislators have published a “Framework For Mitigating Extreme AI Risks.” In brief this framework proposes that developers of models trained on an “enormous amount of computing power” and are “broadly capable; general-purpose and able to complete a variety of downstream tasks; or are intended to be used for bioengineering, chemical engineering, cybersecurity, or nuclear development” must:

1. Implement so called ‘Know your customer requirements,’ that is vet, know, and report customers, especially foreign persons.

2. Notify an “oversight entity” when developing a highly capable model while also incorporating certain safeguards and cybersecurity standards into development.

3. Go through evaluation and obtain a license prior to release to try and prevent models from yielding “bioengineering, chemical engineering, cybersecurity, or nuclear development” risks. License acess would be tiered according to perceived risk levels.

The framework also proposes the creation of a new agency, or investiture of new powers in an exsisting agency or council, to implement these regulations.

Future of Life Institute, US Policy Team

On May 15, 2024, the Senate AI Working Group released “Driving U.S. Innovation in Artificial Intelligence: A Roadmap for Artificial Intelligence Policy in the United States Senate,” which synthesized the findings from the Senate AI Insight Forums into a set of recommendations for Senate action moving forward. The Senate’s sustained efforts to identify and remain abreast of the key issues raised by this rapidly evolving technology are commendable, and the Roadmap demonstrates a remarkable grasp of the critical questions Congress must grapple with as AI matures and permeates our everyday lives.

The need for regulation of the highest-risk AI systems is urgent. The pace of AI advancement has been frenetic, with Big Tech locked in an out-of-control race to develop increasingly powerful, and increasingly risky, AI systems. Given the more deliberate pace of the legislative process, we remain concerned that the Roadmap’s deference to committees for the development of policy frameworks could delay the passage of substantive legislation until it is too late for effective policy intervention.

To expedite the process of enacting meaningful regulation of AI, we offer the following actionable recommendations for such policy frameworks that can form the basis of legislation to reduce risks, foster innovation, secure wellbeing, and strengthen global leadership.

DHS – April 26, 2024

Group Chaired by Secretary Mayorkas Will Consider Ways to Promote Safe and Secure Use of AI in our Nation’s Critical Infrastructure

oday, the Department of Homeland Security announced the establishment of the Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security Board (the Board). The Board will advise the Secretary, the critical infrastructure community, other private sector stakeholders, and the broader public on the safe and secure development and deployment of AI technology in our nation’s critical infrastructure. The Board will develop recommendations to help critical infrastructure stakeholders, such as transportation service providers, pipeline and power grid operators, and internet service providers, more responsibly leverage AI technologies. It will also develop recommendations to prevent and prepare for AI-related disruptions to critical services that impact national or economic security, public health, or safety.

President Biden directed Secretary Alejandro N. Mayorkas to establish the Board, which includes 22 representatives from a range of sectors, including software and hardware companies, critical infrastructure operators, public officials, the civil rights community, and academia. The inaugural members of the Board are:

- Sam Altman, CEO, OpenAI;

- Dario Amodei, CEO and Co-Founder, Anthropic;

- Ed Bastian, CEO, Delta Air Lines;

- Rumman Chowdhury, Ph.D., CEO, Humane Intelligence;

- Alexandra Reeve Givens, President and CEO, Center for Democracy and Technology

- Bruce Harrell, Mayor of Seattle, Washington; Chair, Technology and Innovation Committee, United States Conference of Mayors;

- Damon Hewitt, President and Executive Director, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law;

- Vicki Hollub, President and CEO, Occidental Petroleum;

- Jensen Huang, President and CEO, NVIDIA;

- Arvind Krishna, Chairman and CEO, IBM;

- Fei-Fei Li, Ph.D., Co-Director, Stanford Human-centered Artificial Intelligence Institute;

- Wes Moore, Governor of Maryland;

- Satya Nadella, Chairman and CEO, Microsoft;

- Shantanu Narayen, Chair and CEO, Adobe;

- Sundar Pichai, CEO, Alphabet;

- Arati Prabhakar, Ph.D., Assistant to the President for Science and Technology; Director, the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy;

- Chuck Robbins, Chair and CEO, Cisco; Chair, Business Roundtable;

- Adam Selipsky, CEO, Amazon Web Services;

- Dr. Lisa Su, Chair and CEO, Advanced Micro Devices (AMD);

- Nicol Turner Lee, Ph.D., Senior Fellow and Director of the Center for Technology Innovation, Brookings Institution;

- Kathy Warden, Chair, CEO and President, Northrop Grumman; and

- Maya Wiley, President and CEO, The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights.

Zachary Roth – April 1, 2024

Virginia legislature considered at least 24 AI-related bills, resolutions in the 2024 session

This year’s presidential election will be the first since generative AI — a form of artificial intelligence that can create new content, including images, audio and video — became widely available. That’s raising fears that millions of voters could be deceived by a barrage of political deepfakes.

But, while Congress has done little to address the issue, states are moving aggressively to respond — though questions remain about how effective any new measures to combat AI-created disinformation will be.

Most of the bills require that creators add a disclaimer to any AI-generated content, noting the use of AI, as the NewDEAL Forum report recommends.

Videos

The Ezra Klein Show – March 4, 2025 (01:03:00)

Artificial general intelligence — an A.I. system that can beat humans at almost any cognitive task – is arriving in just a couple of years. That’s what people tell me — people who work in A.I. labs, researchers who follow their work, former White House officials. A lot of these people have been calling me over the last couple of months trying to convey the urgency. This is coming during President Trump’s term, they tell me. We’re not ready.

One of the people who reached out to me was Ben Buchanan, the top adviser on A.I. in the Biden White House. And I thought it would be interesting to have him on the show for a couple reasons: He’s not connected to an A.I. lab, and he was at the nerve center of policymaking on A.I. for years. So what does he see coming? What keeps him up at night? And what does he think the Trump administration needs to do to get ready for the A.G.I. – or something like A.G.I. – he believes is right on the horizon?

PBS NewsHour – October 10, 2024 (06:09)

The Nobel Prize in chemistry went to three scientists for groundbreaking work using artificial intelligence to advance biomedical and protein research. AlphaFold uses databases of protein structures and sequences to predict and even design protein structures. It speeds up a months or years-long process to mere hours or minutes. Amna Nawaz discussed more with one of the winners, Demis Hassabis.

AI Upload – August 26, 2024 (27:29)

Ex-Google CEO Eric Schmidt recently made headlines with some controversial comments about AI during an interview conduced at Stanford University. This interview was taken down at his request after he admitted to misspeaking. But did Eric Schmidt actually let on to something big coming in terms of the future of AI?

BBC Newsnight – October 8, 2024 (09:20)

The Nobel Prize winning ‘Godfather of AI’ speaks to Newsnight about the potential for AI “exceeding human intelligence” and it “trying to take over.” Geoffrey Hinton, former Vice President of Google and sometimes referred to as the ‘Godfather of AI’, has recently won the 2024 Nobel Physics Prize. He resigned from Google in 2023, and has warned about the dangers of machines that could outsmart humans. In May 2024, Faisal Islam spoke to the professor for Newsnight.

AIGRID – April 16, 2024 (29:47)

PBS NewsHour – January 1, 2024 (07:00)

As recently as the early 80s, about three of every four doctors in the U.S. worked for themselves, owning small clinics. Today, some 75 percent of physicians are employees of hospital systems or large corporate entities. Some worry the trend is leading to diminished quality of care and is one reason doctors at a large Midwestern health provider decided to unionize. Fred de Sam Lazaro reports.

PBS NewsHour

The race for supremacy in the age of artificial intelligence has begun. China, the USA and Europe are vying for the top spot. So are individual tech companies and start-ups. Who will determine which technologies will shape the future of humanity? The documentary follows key figures from the tech industry, science and politics who are working on artificial intelligence around the globe. They are tasked with making far-reaching decisions within a very short space of time. How can the technology’s potential be harnessed, while preventing a science fiction dystopia? The potential benefits of the currently emerging super-infrastructure are as limitless as its existential dangers. The latter include disinformation and election manipulation, as well as new forms of warfare and surveillance.

Information

Cathy McMorris Rodgers & Maria Cantwell – April 7, 2024

The American Privacy Rights Act gives Americans fundamental, enforceable data privacy rights, puts people in control of their own data and eliminates the patchwork of state laws.

Washington, D.C. – House Committee on Energy and Commerce Chair Cathy McMorris Rodgers (R-WA) and Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation Chair Maria Cantwell (D-WA) unveiled the American Privacy Rights Act. This comprehensive draft legislation sets clear, national data privacy rights and protections for Americans, eliminates the existing patchwork of state comprehensive data privacy laws, and establishes robust enforcement mechanisms to hold violators accountable, including a private right of action for individuals.

“This bipartisan, bicameral draft legislation is the best opportunity we’ve had in decades to establish a national data privacy and security standard that gives people the right to control their personal information,” said Chair Rodgers and Cantwell. “This landmark legislation represents the sum of years of good faith efforts in both the House and Senate. It strikes a meaningful balance on issues that are critical to moving comprehensive data privacy legislation through Congress. Americans deserve the right to control their data and we’re hopeful that our colleagues in the House and Senate will join us in getting this legislation signed into law.”

“This landmark legislation gives Americans the right to control where their information goes and who can sell it. It reins in Big Tech by prohibiting them from tracking, predicting, and manipulating people’s behaviors for profit without their knowledge and consent. Americans overwhelmingly want these rights, and they are looking to us, their elected representatives, to act,” said Chair Rodgers. “I’m grateful to my colleague, Senator Cantwell, for working with me in a bipartisan manner on this important legislation and look forward to moving the bill through regular order on Energy and Commerce this month.”

“A federal data privacy law must do two things: it must make privacy a consumer right, and it must give consumers the ability to enforce that right,” said Chair Cantwell. “Working in partnership with Representative McMorris Rodgers, our bill does just that. This bipartisan agreement is the protections Americans deserve in the Information Age.”

The American Privacy Rights Act:

Establishes Foundational Uniform National Data Privacy Rights for Americans:

- Puts people in control of their own personal data.

- Eliminates the patchwork of state laws by setting one national privacy standard, stronger than any state.

- Minimizes the data that companies can collect, keep, and use about people, of any age, to what companies actually need to provide them products and services.

- Gives Americans control over where their personal information goes, including the ability to prevent the transfer or selling of their data. The bill also allows individuals to opt out of data processing if a company changes its privacy policy.

- Provides stricter protections for sensitive data by requiring affirmative express consent before sensitive data can be transferred to a third party.

- Requires companies to let people access, correct, delete, and export their data.

- Allows individuals to opt out of targeted advertising.

Gives Americans the Ability to Enforce Their Data Privacy Rights:

- Gives individuals the right to sue bad actors who violate their privacy rights—and recover money for damages when they’ve been harmed.

- Prevents companies from enforcing mandatory arbitration in cases of substantial privacy harm.

Protects Americans’ Civil Rights:

- Stops companies from using people’s personal information to discriminate against them.

- Allows individuals to opt out of a company’s use of algorithms to make decisions about housing, employment, healthcare, credit opportunities, education, insurance, or access to places of public accommodation.

- Requires annual reviews of algorithms to ensure they do not put individuals, including our youth, at risk of harm, including discrimination.

Holds Companies Accountable and Establishes Strong Data Security Obligations:

- Mandates strong data security standards that will prevent data from being hacked or stolen. This limits the chances for identity theft and harm.

- Makes executives take responsibility for ensuring that companies take all actions necessary to protect customer data as required by the law.

- Ensures individuals know when their data has been transferred to foreign adversaries.

- Authorizes the Federal Trade Commission, States, and consumers to enforce against violations.

Focuses on the Business of Data, Not Mainstreet Business

- Small businesses, that are not selling their customers’ personal information, are exempt from the requirements of this bill.

CLICK HERE to read the American Privacy Rights Act discussion draft.

CLICK HERE to read the section-by-section of the discussion draft.

White House

Three months ago, President Biden issued a landmark Executive Order to ensure that America leads the way in seizing the promise and managing the risks of artificial intelligence (AI). The Order directed sweeping action to strengthen AI safety and security, protect Americans’ privacy, advance equity and civil rights, stand up for consumers and workers, promote innovation and competition, advance American leadership around the world, and more.

Today, Deputy Chief of Staff Bruce Reed will convene the White House AI Council, consisting of top officials from a wide range of federal departments and agencies. Agencies reported that they have completed all of the 90-day actions tasked by the E.O. and advanced other vital directives that the Order tasked over a longer timeframe.

Taken together, these activities mark substantial progress in achieving the EO’s mandate to protect Americans from the potential risks of AI systems while catalyzing innovation in AI and beyond. Visit ai.gov to learn more.

Managing Risks to Safety and Security

The Executive Order directed a sweeping range of actions within 90 days to address some of AI’s biggest threats to safety and security. These included setting key disclosure requirements for developers of the most powerful systems, assessing AI’s risks for critical infrastructure, and hindering foreign actors’ efforts to develop AI for harmful purposes. To mitigate these and other risks, agencies have:

- Used Defense Production Act authorities to compel developers of the most powerful AI systems to report vital information, especially AI safety test results, to the Department of Commerce. These companies now must share this information on the most powerful AI systems, and they must likewise report large computing clusters able to train these systems.

- Proposed a draft rule that proposes to compel U.S. cloud companies that provide computing power for foreign AI training to report that they are doing so. The Department of Commerce’s proposal would, if finalized as proposed, require cloud providers to alert the government when foreign clients train the most powerful models, which could be used for malign activity.

- Completed risk assessments covering AI’s use in every critical infrastructure sector. Nine agencies—including the Department of Defense, the Department of Transportation, the Department of Treasury, and Department of Health and Human Services—submitted their risk assessments to the Department of Homeland Security. These assessments, which will be the basis for continued federal action, ensure that the United States is ahead of the curve in integrating AI safely into vital aspects of society, such as the electric grid.

Innovating AI for Good

To seize AI’s enormous promise and deepen the U.S. lead in AI innovation, President Biden’s Executive Order directed increased investment in AI innovation and new efforts to attract and train workers with AI expertise. Over the past 90 days, agencies have:

- Launched a pilot of the National AI Research Resource—catalyzing broad-based innovation, competition, and more equitable access to AI research. The pilot, managed by the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), is the first step toward a national infrastructure for delivering computing power, data, software, access to open and proprietary AI models, and other AI training resources to researchers and students. These resources come from 11 federal-agency partners and more than 25 private sector, nonprofit, and philanthropic partners.

- Launched an AI Talent Surge to accelerate hiring AI professionals across the federal government, including through a large-scale hiring action for data scientists. TheAI and Tech Talent Task Force created by President Biden’s E.O. has spearheaded this hiring action and is coordinating other key initiatives to facilitate hiring AI talent. The Office of Personnel Management has granted flexible hiring authorities for federal agencies to hire AI talent, including direct hire authorities and excepted service authorities. Government-wide tech talent programs, including the Presidential Innovation Fellows, U.S. Digital Corps, and U.S. Digital Service, have scaled up hiring for AI talent in 2024 across high-priority AI projects. More information about the AI Talent Surge is available at ai.gov/apply.

- Began the EducateAI initiative to help fund educators creating high-quality, inclusive AI educational opportunities at the K-12 through undergraduate levels. The initiative’s launch helps fulfill the Executive Order’s charge for NSF to prioritize AI-related workforce development—essential for advancing future AI innovation and ensuring that all Americans can benefit from the opportunities that AI creates.

- Announced the funding of new Regional Innovation Engines (NSF Engines), including with a focus on advancing AI. For example, with an initial investment of $15 million over two years and up to $160 million over the next decade, the Piedmont Triad Regenerative Medicine Engine will tap the world’s largest regenerative medicine cluster to create and scale breakthrough clinical therapies, including by leveraging AI. The announcement supports the Executive Order’s directive for NSF to fund and launch AI-focused NSF Engines within 150 days.

- Established an AI Task Force at the Department of Health and Human Services to develop policies to provide regulatory clarity and catalyze AI innovation in health care. The Task Force will, for example, develop methods of evaluating AI-enabled tools and frameworks for AI’s use to advance drug development, bolster public health, and improve health care delivery. Already, the Task Force coordinated work to publish guiding principles for addressing racial biases in healthcare algorithms.

The table below summarizes many of the activities federal agencies have completed in response to the Executive Order.

AI.Gov

The United States stands to benefit significantly from harnessing the opportunities of AI to improve government services. The federal government is leveraging AI to better serve the public across a wide array of use cases, including in healthcare, transportation, the environment, and benefits delivery. The federal government is also establishing strong guardrails to ensure its use of AI keeps people safe and doesn’t violate their rights.

Commentary

CNN, Rizwan Virk – April 9, 2024

In the 1968 film “2001: A Space Odyssey,” audiences found themselves staring at one of the first modern depictions of an extremely polite but uncooperative artificial intelligence system, a character named HAL. Given a direct request by the sole surviving astronaut to let him back in the spaceship, HAL responds: “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Recently, some users found themselves with a similarly (though less dramatic) polite refusal from Gemini, an integrated chatbot and AI assistant that Google rolled out as a competitor to OpenAI’s ChatGPT. When asked, Gemini politely refused in some instances to generate images of historically White people, such as the Vikings.

Unlike the fictional HAL, Google’s Gemini at least offered some explanation, saying that only showing images of White persons would reinforce “harmful stereotypes and generalizations about people based on their race,” according to Fox News Digital.

The situation quickly erupted, with some critics dubbing it a “woke” AI scandal. It didn’t help when users discovered that Gemini was creating diverse but historically inaccurate images. When prompted to depict America’s Founding Fathers, for example, it generated an image of a Black man. It also depicted a brown woman as the Pope, and various people of color, including a Black man, in Nazi uniforms when asked to depict a 1943 German soldier.

About

Overview

Party Positions

Republican Party platform: In 2020, the Republican Party decided not to write a platform for that presidential election cycle, instead simply expressing its support for Donald Trump’s agenda.

- Go here to see a PDF on 2016 Republican Platform.

- Go to this Wikipedia entry to read “Political positions of Donald Trump”.

Democratic Party platform:

- Go here to read the Democratic Party’s plaform on the DNC’s website

- Go to this Wikipedia entry to read the”Political positions of the Democratic Party”

Challenges

Technical Challenges:

- Understanding and modeling human intelligence: AGI requires a comprehensive understanding of human cognition, including reasoning, problem-solving, language, and social interaction.

- Developing flexible and adaptive algorithms: AGI systems must be able to learn and adapt to new situations and environments without explicit programming.

- Scalability and efficiency: AGI requires immense computational power and efficiency to process and manage large amounts of data.

- Robustness and safety: AGI systems must be designed to be robust against errors, biases, and security threats, ensuring their safe and ethical operation.

Philosophical Challenges:

- Defining consciousness and self-awareness: AGI raises questions about the nature of consciousness and whether artificial systems can truly experience subjective experiences.

- Moral agency and responsibility: AGI systems may be capable of making independent decisions, leading to ethical considerations about their accountability and potential impact on society.

- Singularity and existential risks: Some experts argue that the development of AGI could lead to a “singularity” where artificial intelligence surpasses human intelligence and poses existential risks to our species.

Social Challenges:

- Impact on employment and economy: AGI could automate tasks currently performed by humans, potentially displacing workers and disrupting the job market.

- Social equality and bias: AGI systems may inherit or amplify existing societal biases, leading to unfair outcomes and exacerbating social inequalities.

- Public perception and trust: The development and deployment of AGI require public acceptance and trust, which can be challenging due to concerns about job displacement, privacy, and the potential for misuse.

Other Challenges:

- Lack of standardized benchmarks and metrics: There is a need for standardized benchmarks and metrics to evaluate and compare the progress of AGI research.

- Collaboration and knowledge sharing: AGI development requires collaboration between researchers, industry, and policymakers to share ideas, resources, and ensure responsible advancement.

- Long-term sustainability: The research and development of AGI is an endeavor that requires sustained funding and commitment.

Solutions

1. Symbolic Representation and Reasoning:

- Symbolic AI: Develop expressive languages and reasoning systems that can manipulate symbolic knowledge and make inferences about the world.

- Knowledge Representation: Create knowledge bases that capture the semantic and structural relationships of the world, allowing AGIs to understand and reason with complex concepts.

2. Perception and Grounding:

- Multimodal Sensor Fusion: Integrate data from multiple sensors (e.g., vision, language, touch) to create a comprehensive understanding of the physical world.

- Object Recognition and Manipulation: Develop algorithms that can identify, track, and interact with objects in the environment in a meaningful way.

3. Natural Language Understanding and Generation:

- NLP Techniques: Advance natural language processing techniques to enable AGIs to communicate effectively with humans and understand the nuances of language.

- Text-to-Speech and Speech-to-Text: Develop robust systems for translating text into speech and speech into text to facilitate human-AGI communication.

4. Memory and Learning:

- Long-Term Memory: Design memory systems that can store and retrieve vast amounts of information in a way that supports efficient reasoning.

- Lifelong Learning: Enable AGIs to continuously learn from new experiences and adapt their knowledge and capabilities over time.

5. Planning and Decision-Making:

- Goal-Oriented Planning: Develop algorithms that can generate and evaluate plans to achieve specific goals in complex environments.

- Ethical Considerations: Incorporate ethical principles into decision-making algorithms to ensure that AGIs make responsible and socially acceptable choices.

6. Embodiment and Interaction:

- Physical Embodiment: Design and build physical bodies for AGIs to enable them to interact with the world through motion and manipulation.

- Human-Computer Interaction: Develop intuitive interfaces and interaction protocols that allow humans and AGIs to collaborate effectively.

7. Consciousness and Self-Awareness:

- Artificial Consciousness: Explore the nature of consciousness and develop models that can emulate the subjective experiences of beings.

- Self-Reflection and Introspection: Create algorithms that allow AGIs to reflect on their own thoughts, actions, and motivations.

8. Computational Challenges:

- Massive Computational Power: Develop efficient algorithms and hardware architectures that can handle the immense computational demands of AGI.

- Optimization Algorithms: Advance optimization techniques to train AGIs effectively and discover solutions to complex problems.

9. Safety and Control: