Russia and the United States maintain one of the most important, critical and strategic foreign relations in the world. Both nations have shared interests in nuclear safety and security, nonproliferation, counterterrorism, and space exploration. Due to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, relations became very tense after the United States imposed sanctions against Russia. Russia placed the United States on a list of “unfriendly countries”, along with Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, Singapore, European Union members, NATO members (except Turkey), Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Micronesia and Ukraine.

- In the ‘About’ section of this post is an overview of the issues or challenges, potential solutions, and web links. Other sections have information on relevant legislation, committees, agencies, programs in addition to information on the judiciary, nonpartisan & partisan organizations, and a wikipedia entry.

- To participate in ongoing forums, ask the post’s curators questions, and make suggestions, scroll to the ‘Discuss’ section at the bottom of each post or select the “comment” icon.

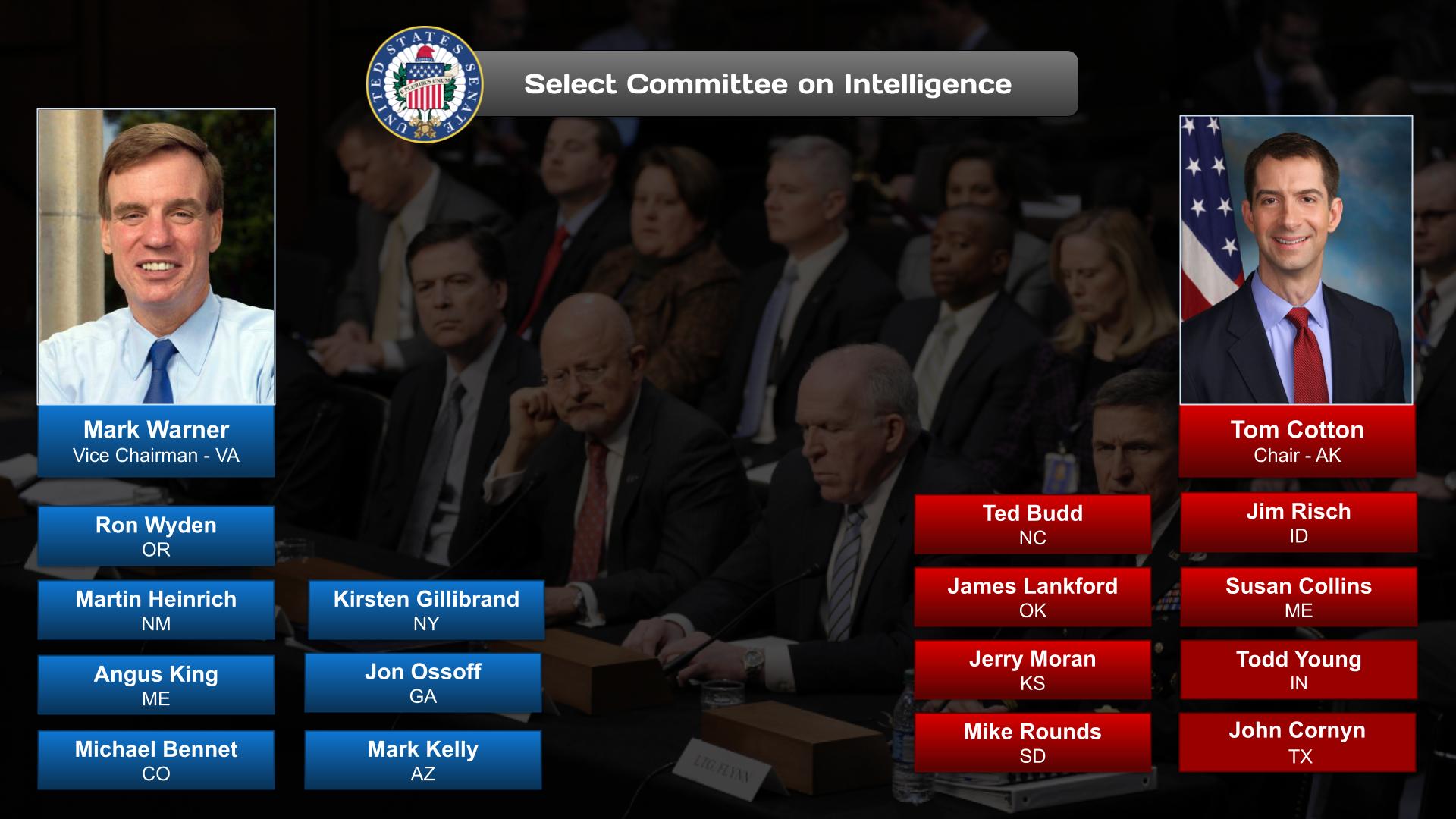

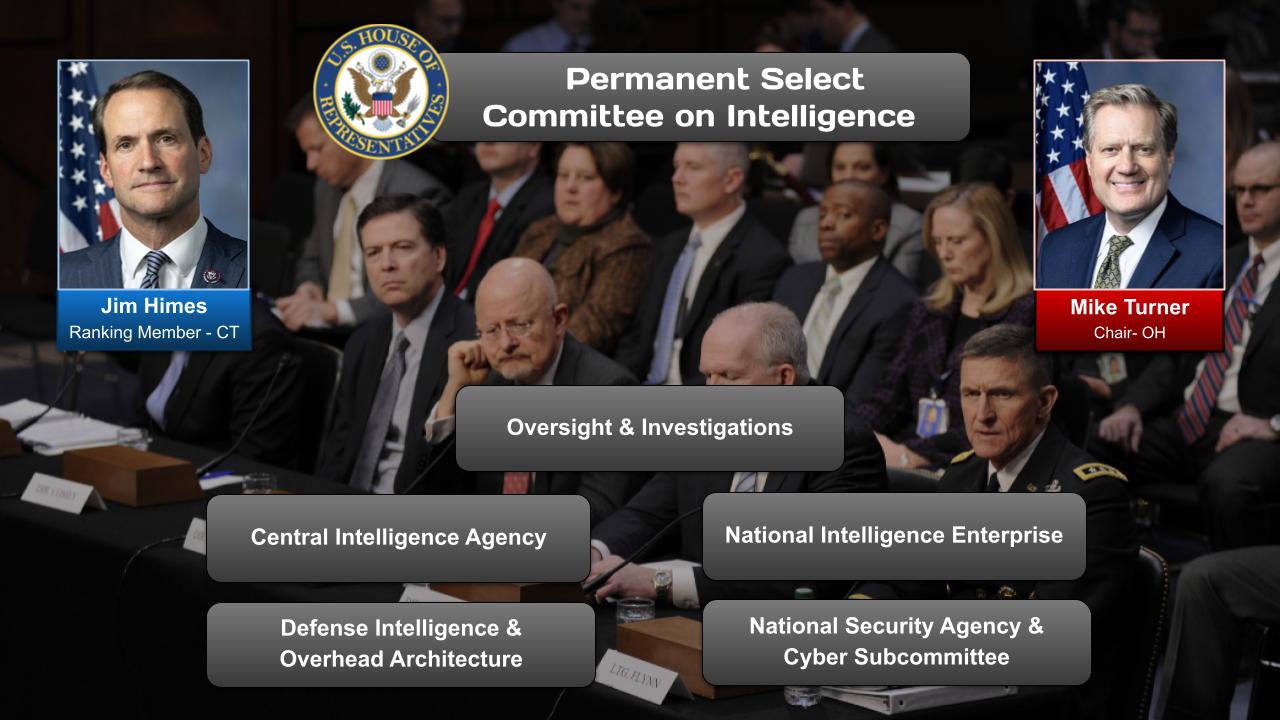

The Russia category has related posts on government agencies and departments and committees and their Chairs.

FRONTLINE PBS – 24/01/2023 (52:47)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aJI8XTa_DII&t=1691s

FRONTLINE investigates Russian President Vladimir Putin’s clashes with five American presidents as he’s tried to rebuild the Russian empire.

Drawing on in-depth conversations with insiders from five U.S. presidential administrations, former U.S. intelligence leaders, diplomats, Russian politicians, authors and journalists, “Putin and the Presidents” reveals how the miscalculations and missteps of multiple American presidents over two decades paved the way for Putin’s attack on Ukraine — as seen through the eyes of people who were in the room.

The documentary traces how, prior to launching the war on Ukraine, Putin tested the waters by defying American presidents for 20 years — including by invading Georgia, seizing Crimea, and interfering in a U.S. presidential election. The documentary provides unique insight into the icy relationship between Putin and current U.S. President Joe Biden, both of whom were shaped by the Cold War, and into the evolution of Putin’s grievances with the U.S. and the West.

As Russia’s war on Ukraine continues, “Putin and the Presidents” gives essential context for this historic moment.

“Putin and the Presidents” is a FRONTLINE production with the Kirk Documentary Group. The director is Michael Kirk. The producers are Michael Kirk, Mike Wiser and Vanessa Fica. The writers are Michael Kirk and Mike Wiser. The reporter is Vanessa Fica. The editor-in-chief and executive producer of FRONTLINE is Raney Aronson-Rath.

Explore additional reporting on “Putin and the Presidents” on our website: https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/do…

OnAir Post: Russia