Food and housing insecurity are two interconnected issues that can have significant impacts on individuals and communities. They often occur together, creating a vicious cycle where limited access to affordable housing can hinder the ability to purchase nutritious food, and vice versa.

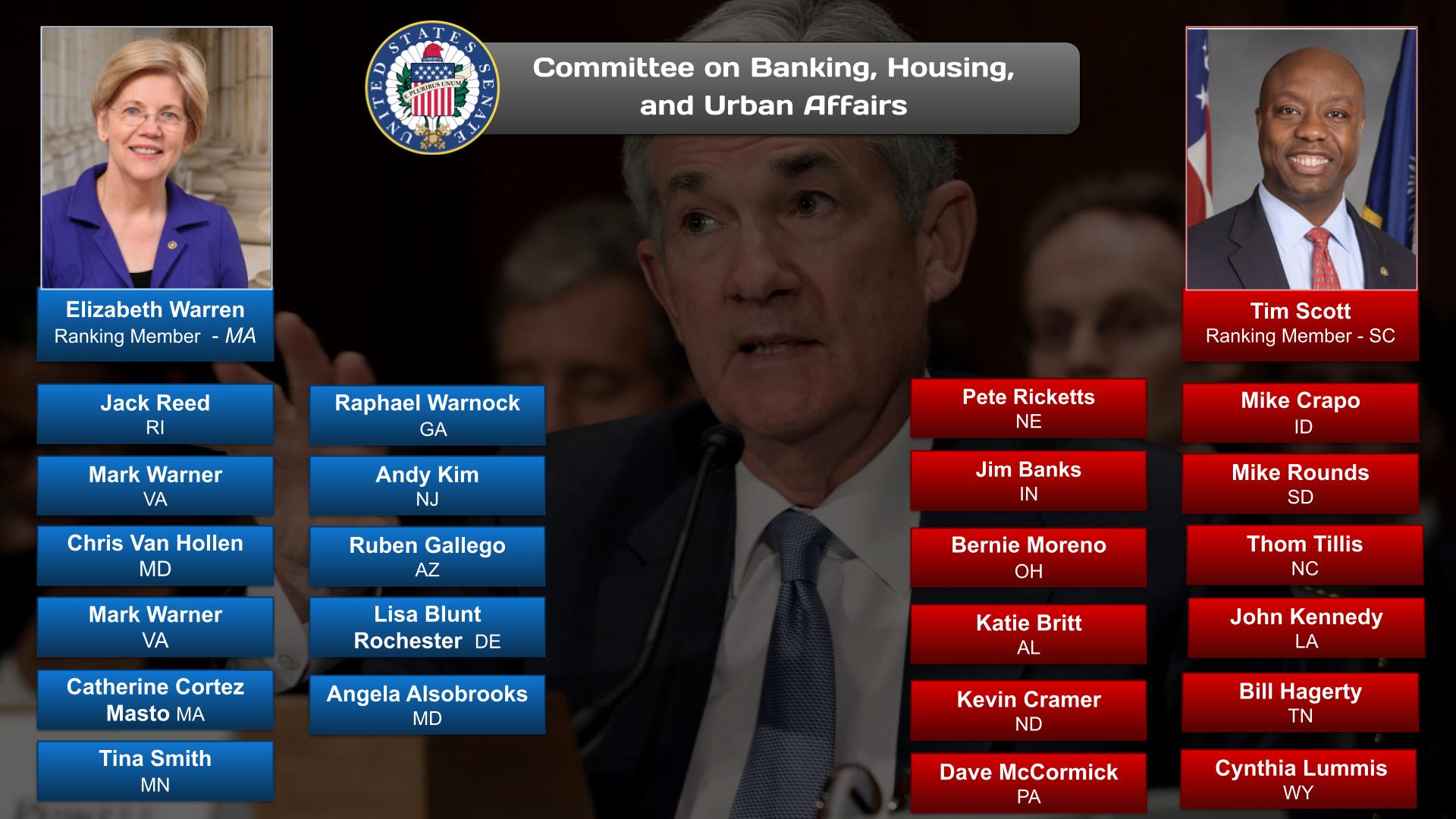

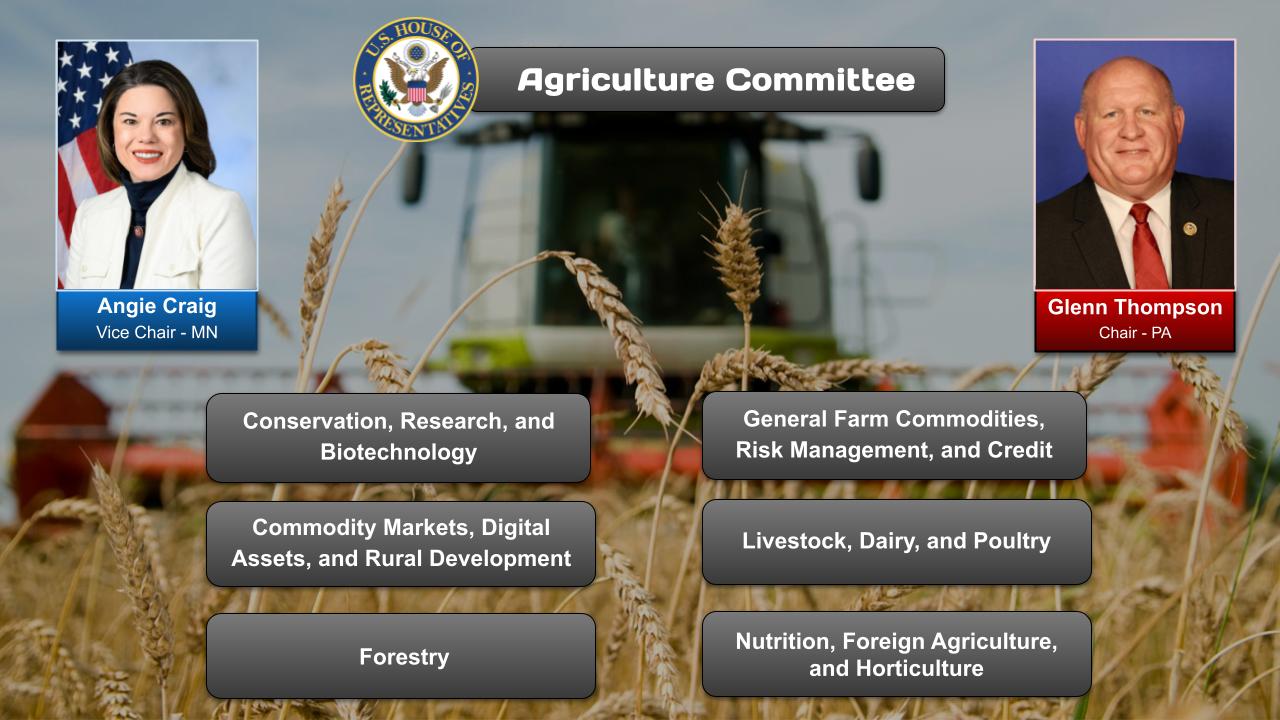

- There are many issues related to Food & Housing that Congress is looking to address with legislation. In the ‘About’ section of this post is an overview of the issues and potential solutions, party positions, and web links. Other sections have information on relevant committees, chairs, & caucuses; departments & agencies; and the judiciary, nonpartisan & partisan organizations, and a wikipedia entry.

- To participate in ongoing forums, ask the post’s curators questions, and make suggestions, scroll to the ‘Discuss’ section at the bottom of each post or select the “comment” icon.

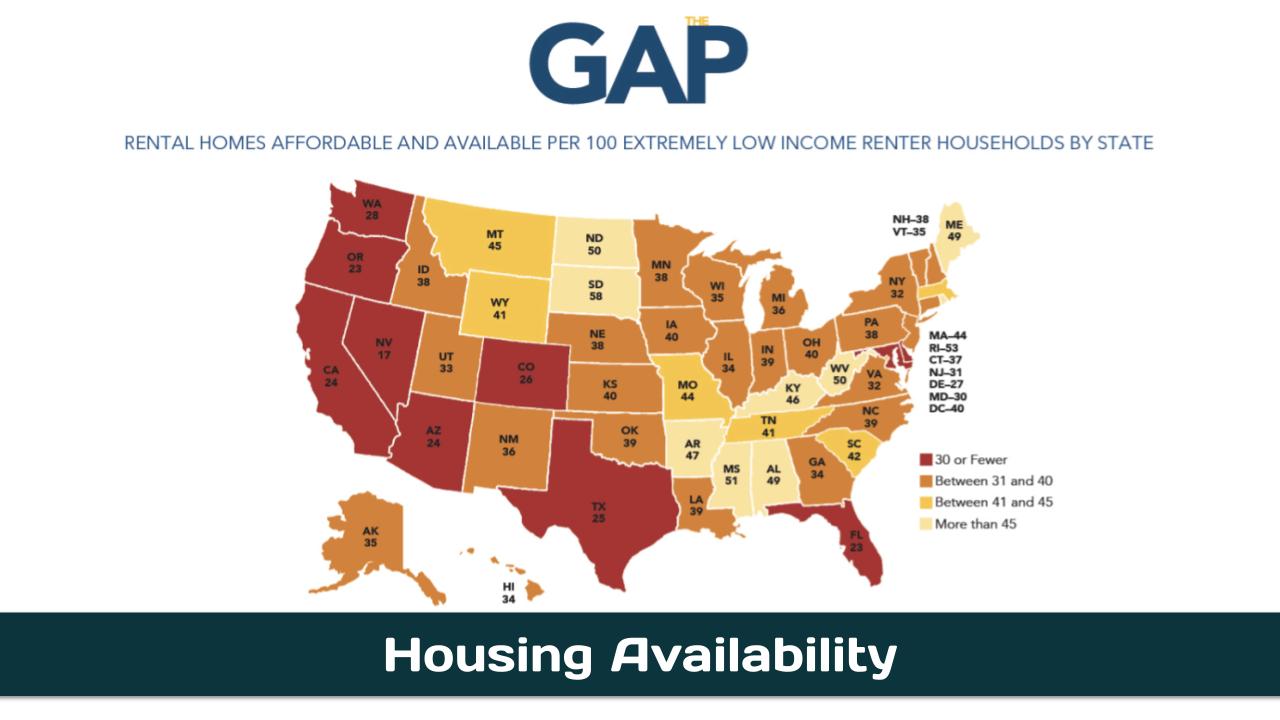

The Food & Housing category has related posts and three posts on issues of particular focus: Food Insecurity, Housing Availability, and Sustainable Agriculture.

Vox – 16/08/2021 (09:41)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Flsg_mzG-M

Over the past year, housing prices in the US rose precipitously. Low interest rates and millennials’ entry into the market spiked demand across the nation, leading housing prices in some cities to increase by more than 20 percent in one year, and crushing the dreams of many would-be homeowners.

OnAir Post: Food & Housing