In common usage, Climate Change describes global warming—the ongoing increase in global average temperature—and its effects on Earth’s climate system. Climate change in a broader sense also includes previous long-term changes to Earth’s climate. The current rise in global average temperature is more rapid than previous changes, and is primarily caused by humans burning fossil fuels.

- In the ‘About’ section of this post is an overview of the issues or challenges, potential solutions, and web links. Other sections have information on relevant legislation, committees, agencies, programs in addition to information on the judiciary, nonpartisan & partisan organizations, and a wikipedia entry.

- To participate in ongoing forums, ask the post’s curators questions, and make suggestions, scroll to the ‘Discuss’ section at the bottom of each post or select the “comment” icon.

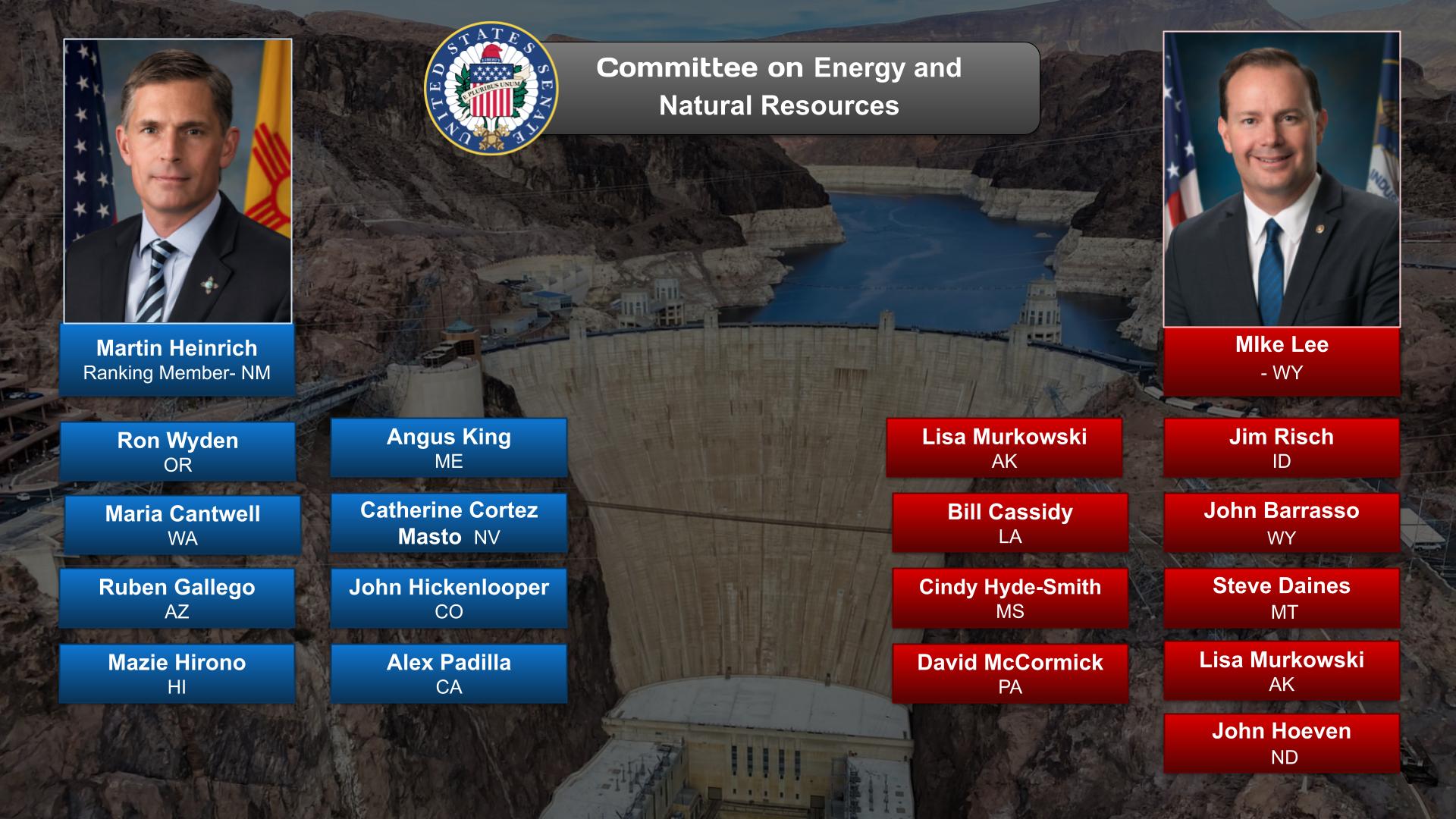

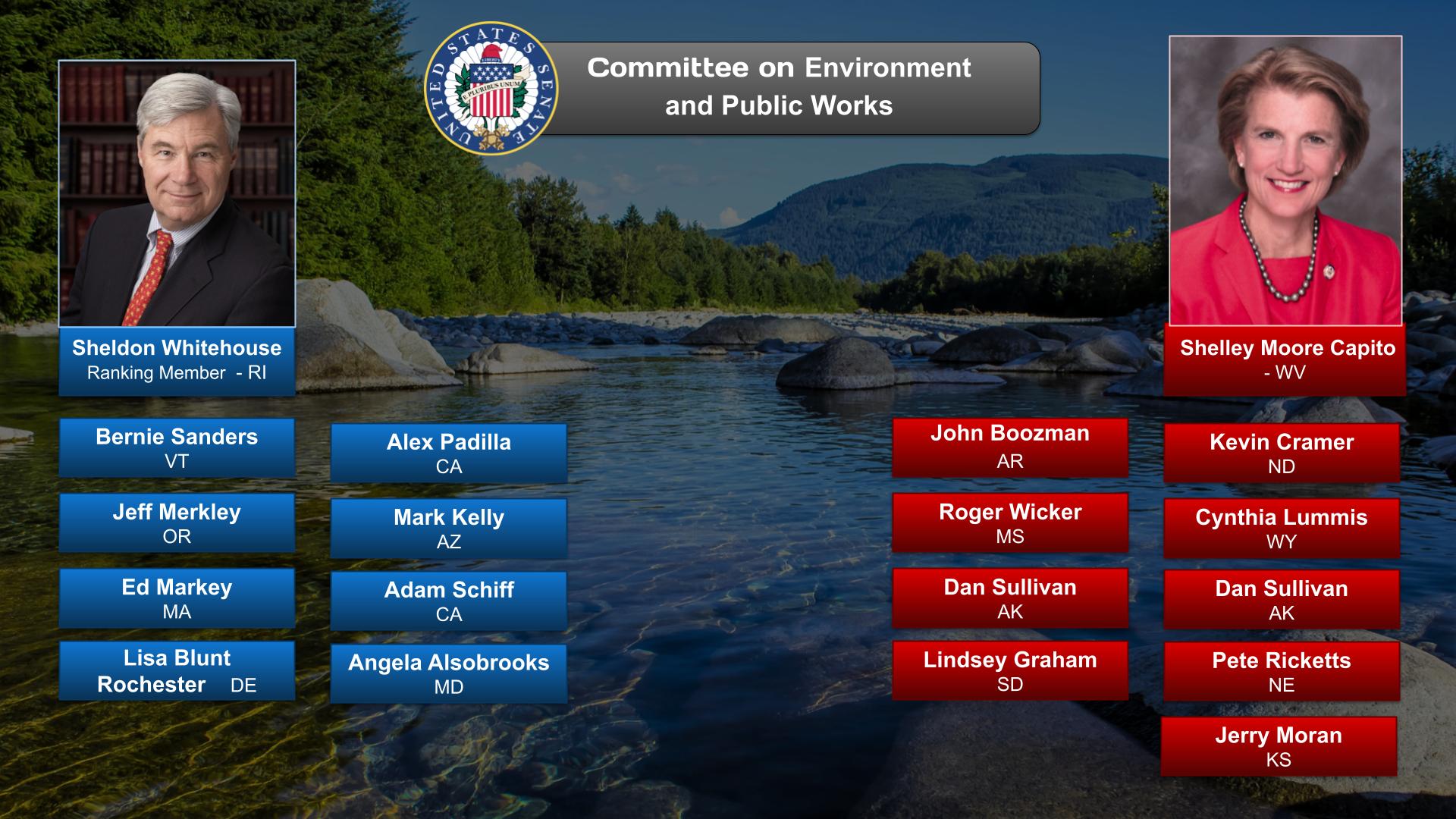

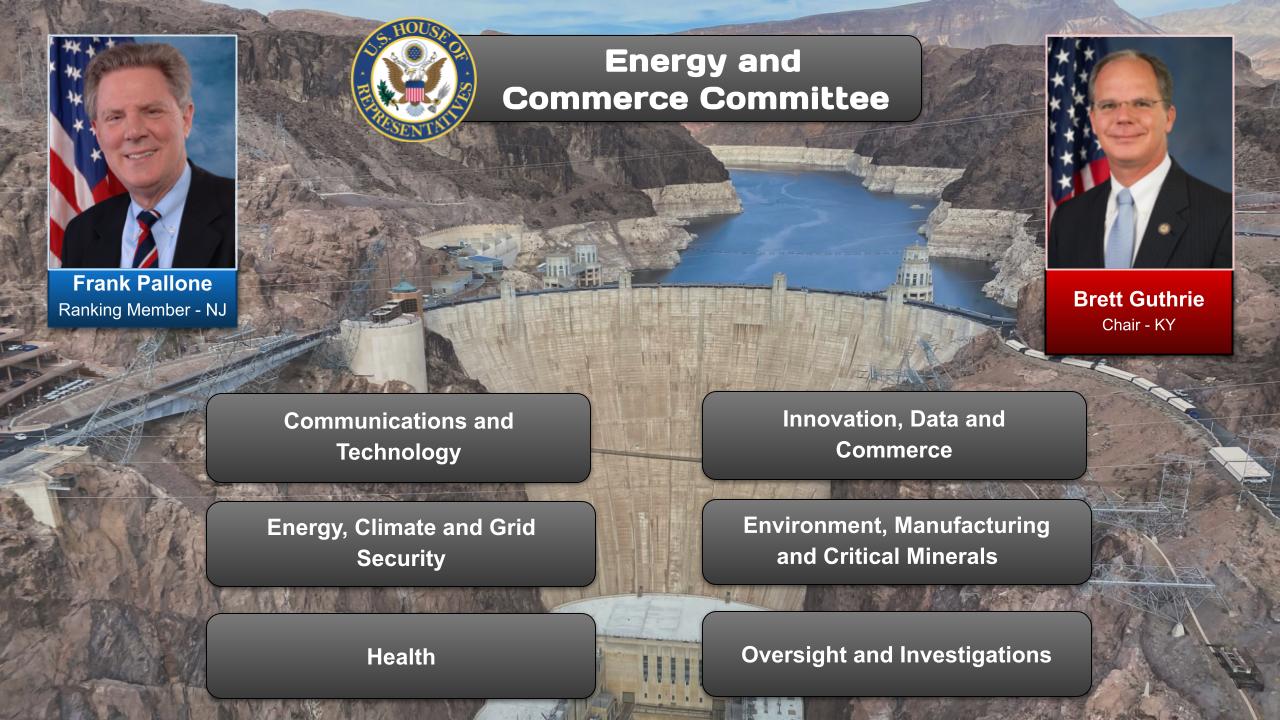

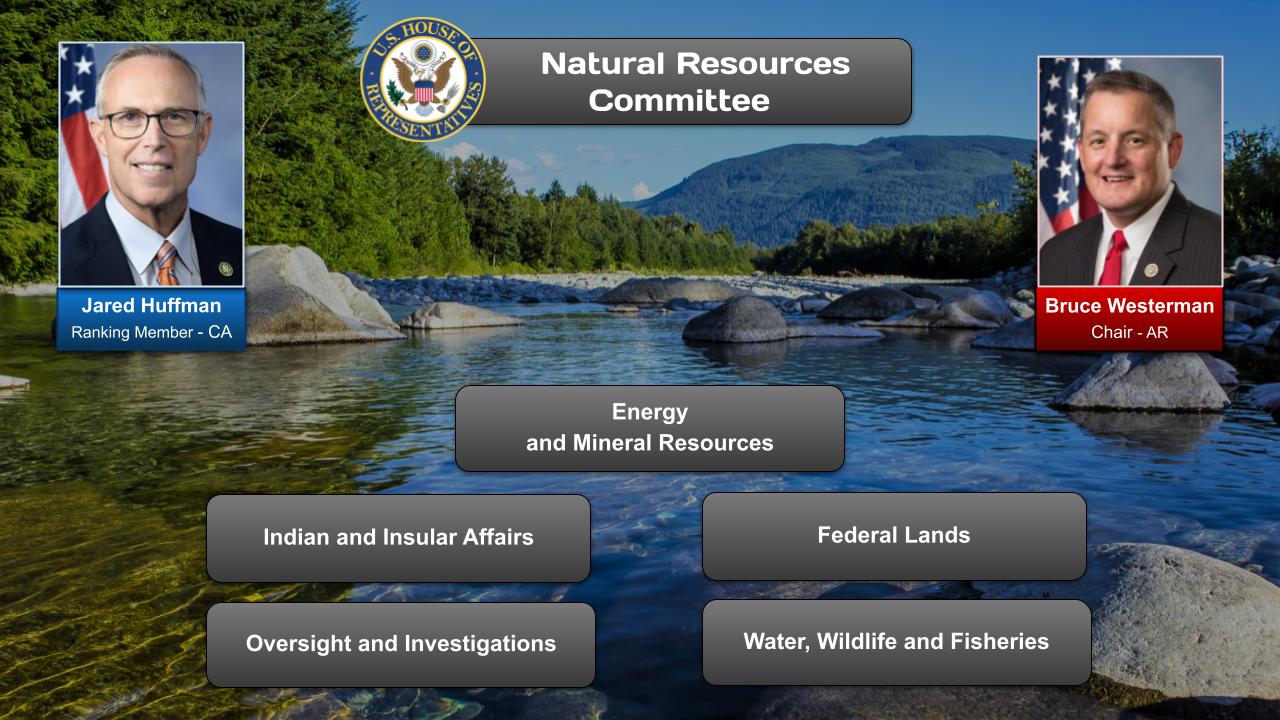

The Climate Change category has related posts on government agencies and departments and committees and their Chairs.

Vox – 19/04/2017 (09:44)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DkZ7BJQupVA

The biggest problem for the climate change fight isn’t technology – it’s human psychology.

This is the first episode of Climate Lab, a six-part series produced by the University of California in partnership with Vox. Hosted by Emmy-nominated conservation scientist Dr. M. Sanjayan, the videos explore the surprising elements of our lives that contribute to climate change and the groundbreaking work being done to fight back. Featuring conversations with experts, scientists, thought leaders and activists, the series takes what can seem like an overwhelming problem and breaks it down into manageable parts: from clean energy to food waste, religion to smartphones. Check back next Wednesday for the next episode or visit http://climate.universityofcalifornia… for more.

OnAir Post: Climate Change