Summary

The North Carolina General Assembly is the bicameral legislature of the State government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. The General Assembly meets in the North Carolina Legislative Building in Raleigh, North Carolina, United States.

Source: Wikipedia

OnAir Post: NC General Assembly

News

NC Policy Watch, – May 17, 2021

The state legislature marked “crossover” last week, the point at which most bills must pass at least one chamber to have a chance of becoming law this session.

House members had filed 969 bills by the end of last week, and senators had filed 721.

The House passed 336 bills by the crossover deadline — a little more than a third — and the Senate passed 156, about a quarter of those filed. About two dozen have already become law.

About

Source: Wikipedia

Web Links

Wikipedia

Contents

The North Carolina General Assembly is the bicameral legislature of the state government of North Carolina. The legislature consists of two chambers: the Senate and the House of Representatives. Vested with the state's legislative power by the Constitution of North Carolina, the General Assembly meets in the North Carolina State Legislative Building in Raleigh.

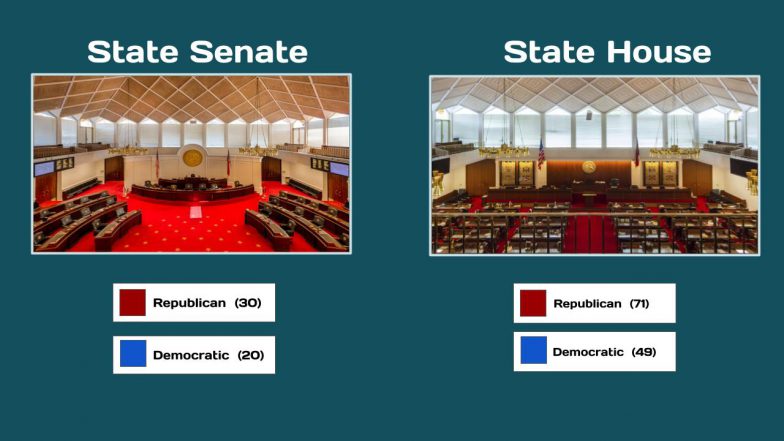

The House of Representatives has 120 members, while the Senate has 50 members. All represent districts and are elected to serve two year-terms. There are no term limits for either chamber. Together, the bodies write the state laws of North Carolina—known as the General Statutes and create the state's biennial budget. Most legislation is subject to the potential veto of the governor, though such a veto can be overruled with a three-fifths majority vote. The legislature can also impeach state officials and propose constitutional amendments.

Both chambers are currently controlled by the Republican Party, but they only hold veto override power in the Senate, holding 1 seat shy of a supermajority in the House of Representatives.

History

Colonial period

In 1663, King Charles II of England granted a royal charter to eight lords proprietor to establish the colony of Carolina in North America.[1] Under the terms of the charter, regular management of the colony was to be overseen by a governor and a council. An assembly consisting of two representatives from each county elected by freeholders was to have the power to write laws with the approval of the governor, his council, and the lords proprietor. This system of government was ultimately never implemented in the area which eventually became North Carolina.[2] In early 1665 the lords proprietor promulgated a constitution for Carolina, the Concessions and Agreement. The document provided for a governor, a council of six to 10 men chosen by the governor with the consent of the lords, and an elected assembly. It also stipulated that the assembly's consent was required for taxes to be levied and that vacancies in the assembly were to be filled by elections called by the governor and his council.[3] A new royal charter for Carolina was granted in 1665 and required the forming of an assembly.[4]

After receiving his commission, Carolina Governor William Drummond summoned a body of freemen who selected 12 deputies to represent their interests.[5] Together with the governor and his council, the deputies served as a provisional legislature for Albemarle County[a] and eventually was named the General Court and Committee. It held its first meeting in the spring of 1665. When the governor and his deputy were absent, the assembly would designate a president or speaker to lead its sessions. Approximately two years later, the temporary assembly divided the county into four precincts: Chowan, Currituck, Pasquotank, and Perquimans. The freemen in each precinct were to convene at the beginning of every year to elect five representatives for the permanent assembly. The first election occurred on January 1, 1668.[7]

While required to abide by the Concessions and support the interests of the lords proprietor, the assembly was powerful and largely left to manage itself. It decided the length and locations of its own sessions, when it adjourned, and its own quorum. It wrote laws, levied taxes, created courts, incorporated towns, determined the sites of ports and forts, regulated the militia, allotted land, and granted citizenship. Laws passed by the legislature held effect for 18 months and were sent to England for ratification by the lords. The lords could refuse to ratify laws and let them expire.[8] From 1692 to 1712, North Carolina and South Carolina were organized as one Province of Carolina. The colony had one governor but North Carolina retained its own council and assembly.[1] After 1731, the members of the governor's council were chosen by the Privy Council and were responsible to the British king.[9]

During the period of royal control after 1731, North Carolina's governors were issued sets of secret instructions from the Privy Council's Board of Trade. The directives were binding upon the governor and dealt with nearly all aspects of colonial government. As they were produced by officials largely ignorant of the political situation in the colony and meant to ensure greater direct control over the territory, the instructions caused tensions between the governor and the General Assembly. The assembly controlled the colony's finances and used this as leverage by withholding salaries and appropriations, sometimes forcing the governors to compromise and disregard some of the Board of Trade's instructions.[10] Particularly after 1760, the lower house increasingly viewed itself as the representative of the colonists' interests in opposition to the British Crown's interests as relayed by the governor and the council.[11] Frequent tensions between Governor Josiah Martin—a firm supporter of the secret instructions—and the assembly in the 1770s led the latter to establish a committee of correspondence[10] and accelerated the colony's break with Great Britain.[12]

Revolutionary period

In 1774, the people of the colony elected a provincial congress, independent of the royal governor, as the American Revolution began. Inspired by the structure of the lower house of the General Assembly and organized in part by House Speaker John Harvey, its purpose was to chose delegates to send to the Continental Congress. In addition to this, the congress adopted punitive measures against Great Britain for its Intolerable Acts and empowered local committees to govern the state as royal control dissipated. A second congress in April 1775 adopted additional economic measures against Great Britain,[13] leading Governor Martin to dissolve the colonial assembly[14] before fleeing the colony. There would be five provincial congresses. The fifth Congress created the first constitution in 1776.[13] This constitution was not submitted to a vote of the people.[15] The Congress simply adopted it and elected Richard Caswell, the last president of the Congress, as acting governor until the new legislature was elected and seated.[13][16]

Per the terms of the constitution, North Carolina had a government with a separation of powers divided amongst executive, legislative, and judicial branches, though the legislative branch retained the most power and wielded significant influence over the others.[17][18] The General Assembly, vested with the state's legislative power, was made a bicameral body, consisting of a Senate made up of one member from each county in the state and a House of Commons with two members from each county and one from each of several specially designated "borough towns".[19][20][21] As such, the size of the legislature would grow with the addition of new counties and borough towns.[20] Property requirements stipulated that House members had to own at least 100 acres and senators at least 300 to serve.[19] In order to vote in a Senate election, one had to own at least 50 acres, while participants in House elections only had to pay taxes.[22] No restrictions were placed on race for the purposes of suffrage.[23] Elections for members of both houses were to beheld annually, and each house was responsible for electing its own officers.[20] The assembly was responsible for electing the governor, the Council of State, the state treasurer, the secretary of state, the attorney general, officers of the state militia, and all judges.[19][24] There were few limits on its powers.[25]

The first North Carolina General Assembly was convened on April 7, 1777, in New Bern, North Carolina.[26] Due to the outbreak of hostilities and in an effort to present itself to the public, North Carolina's legislature met in various locations throughout the war, though most often in New Bern, Halifax, and Hillsborough.[27][28] The assembly initially organized the state's war effort and structured the militia itself and directed oversight through committees, though when this proved unsatisfactory it created separate boards with supervisory authority.[29] In September 1781, British forces captured the governor and several members of the General Assembly during a raid on Hillsborough. The war ended in 1783.[14]

Antebellum period and Civil War

The General Assembly's primacy in state government was largely unchallenged until 1787, when the North Carolina Court of Conference found a state law in violation of the state constitution in the case Bayard vs. Singleton and overturned it, thus helping to establish a principal of judicial review.[30][31][32] In 1791, the General Assembly appointed a commission to designate a permanent seat of state government, and the following year the legislature fixed the seat at the planned city of Raleigh.[33] Construction of a North Carolina State House began in Raleigh in 1792 and became the meeting place for the General Assembly in 1794. It was enlarged in 1820 and burnt down in 1831.[27] The legislature convened in the governor's residence in the interim and briefly considered relocating their seat before appropriating money to erect a new capitol in Raleigh.[34] The North Carolina State Capitol was completed in 1840.[35]

In 1834 the General Assembly voted narrowly in favor of a measure to establish a convention to amend the state constitution.[36] The subsequent convention in 1835 offered significant changes to the state's constitution which were ratified in a popular referendum.[37] Amendments set the number of senators at 50 and the number of commoners in the House at 120.[15] Borough towns were terminated. Senate districts were no longer required to be limited to individual counties, but instead be coterminous with which counties were to be included in them and based on a judgement of approximate wealth measured by tax receipts.[38] Sessions for the legislature were changed from annual to biennial[39] and the terms of legislators were lengthened accordingly to two years.[40] The office of governor was also made popularly elective.[40] A new constitutional amendment process was also established, whereby the legislature could by a two-thirds majority vote convene a convention or could propose amendments subject to popular referendum after passing them in succeeding sessions after first a three-fifths and then a two-thirds majority vote.[41] Suffrage for the purposes of legislative elections was limited to white men.[42] In 1857, property requirements for qualifying to vote in Senate races were abolished.[43]

In May 1861, at the urging of the governor, the General Assembly passed a resolution calling for the establishment of a convention to consider seceding from the United States. Later that month the convention met in Raleigh and adopted an Ordinance of Secession and adopted the Constitution of the Confederate States.[44] The convention met several times from then until November 1862, during which time it served as a transitional government for the state, superseding the authority of the General Assembly[b] and making changes to state law on its own. After the president of the convention declined to convene it to discuss issues of wartime speculation and extortion, authority returned to the state's other civil leaders and institutions.[46] During the Civil War the General Assembly continued to meet in regular biennial sessions, but also convened in seven extraordinary sessions to address wartime issues.[47]

Reconstruction era

In 1868, a new constitution was crafted by a convention and ratified by popular vote. The document provided for universal male suffrage and abolished all property requirements and religious tests for officeholders.[15][c] It changed the name of the House of Commons to the House of Representatives[19] and changed the Senate apportionment from districts based on taxes paid to a system which accounted for population.[49] The constitution also reverted legislative sessions from a biennial schedule to annual.[50] The document created the office of lieutenant governor which was to be filled by popular statewide election. It replaced the speaker of the Senate as that body's presiding officer and assumed the former office's role in succeeding to the governorship in the event it became vacant.[51] The constitution made numerous state executive offices and judgeships subject to popular election and provided for elected local governments, diminishing the legislature's influence over these institutions.[52] It also laid out specific limitations on the legislature's taxation power, ability to incur public debts, and on its discretion as far as certain areas of policy.[53]

With the ratification of the new constitution and the enfranchisement of black men, blacks were first elected to the General Assembly in 1868.[54][55] In the legislative term lasting from 1868 to 1870, three blacks served in the Senate and 17 served in the House of Representatives.[56] Black men were consistently elected to the legislature in similar numbers in the following years before declining in strength in the late 1880s and early 1890s.[57] Between 1868 and 1901, a total of 97 black legislators served.[58]

In 1873, a constitutional amendment changed sessions back to biennial. In 1875, the General Assembly convened a new constitutional convention.[59] This led to the ratification of several amendments the following year which chiefly functioned to strengthen the power of the legislature. The changes allowed for the legislature to create additional executive offices and provide for their selection, to create and define the jurisdiction of new lower courts, and to replace elected local governments with their own chosen officials.[60] Lastly, the amendments eased the future amendment process for the constitution, allowing any proposed change which had been approved by three-fifths of the vote of each house of the General Assembly to be scheduled for ratification in a referendum.[61]

Republican Party members dominated the legislature from 1868 to 1870. From then until the 1895, control rested with members of the Conservative Party/Democratic Party.[62] In 1894, Republicans and members of the incipient Populist Party agreed to cooperate and as a coalition won a majority in both the House and Senate.[63][64][65] Democrats dubbed this alliance "Fusionism".[65] Black legislative representation briefly rebounded during the Fusionist era, with 12 black candidates winning seats in 1896.[66] Two years later, Democrats regained a majority in the legislature. They passed new voter registration laws and proposed a constitutional amendment to create barriers to voter registration through poll taxes, and literacy tests. The amendment was ratified in a referendum in 1900.[64] These measures disproportionately effected poor black voters and effectively disenfranchised most black people in the state.[64] Black representation in the legislature ceased.[67] In 1916, the constitution was amended to prohibit the General Assembly from passing local laws on various subjects in an attempt to reorient its focus towards issues of general concern to the state.[68]

Modernization

Institutional enhancements

The General Assembly began increasing the length of its sessions and hiring more support staff in the 1940s and 1950s.[69] In 1955, the legislature began extensively using interim study commissions to investigate and compile reports on matters of interest to legislators in between sessions and inform future proposals.[70] In 1959, the General Assembly organized a commission to design and fund a new, larger meeting place to accommodate the body, its staff, and improve the delivery of services to the legislators.[71] Construction began in 1961 and the General Assembly held its first session in the new North Carolina State Legislative Building in February 1963.[72] In 1968, the General Assembly, in tandem with national trends towards state legislative professionalization, hired its first legislative services officer,[73] initially dubbed its administrative officer. The following year the assembly by law created the Legislative Services Commission to oversee the legislative services officer and the administrative affairs of its operations.[74][75] Professional, clerical, budget disbursement, and resource procurement services provided by the commission to the legislature steadily increased over the following years.[76] The 1969 session also marked the first time the body used a computer to keep records of its bills and track their progress.[77][d]

In the early 1970s, Democratic legislators, spurred in part by the election of a Republican governor in 1972, began an effort to strengthen the General Assembly's power and influence in state government which continued into the 1980s. As a result, the legislature hired its own research staff, created an independent judicial office to review administrative affairs in the state bureaucracy, and began appointing its own members to state board and commissions, though the latter practice was ruled unconstitutional by the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1982.[79] The legislature returned to meeting annually in 1973[80][e] and also authorized committees to meet and work in the interim between sessions.[84] In 1977, the state constitution was amended to allow for governors and lieutenant governors to seek second terms. Shortly thereafter, the House, feeling threatened by the strengthened positions of the governor and Senate leadership, broke from a decades-long trend and began electing speakers to successive terms.[85][86] The legislature's influence in state politics continued to increase through the late 20th century and early 21st century.[87][88]

Reapportionment and changes in representation

Lillian Exum Clement became the first female member of the General Assembly when she joined the House of Representatives in 1921.[89] Gertrude Dills McKee became the first woman to be elected to the State Senate in 1930.[90] Female representation slowly increased in the following decades.[91][92]

For hundreds of years North Carolina's legislative representation was apportioned such that each county had at least one representative in the House and that all Senate districts were supposed to contain approximately equal populations, though the latter tenant was undermined by a constitutional requirement that no counties be split between different districts. As a result, by the 1960s, rural constituents were significantly overrepresented in the legislature.[93] Following developments in federal jurisprudence in the early 1960s that led to the creation of the principle of one man, one vote, in 1965, a U.S. District Court panel ruled that the state's legislative districts were unconstitutional.[94] As a result, in the 1960s and 1970s the legislature designed districts in a manner which significantly rebalanced the representation of the state in a more equitable manner.[95] In the mid-1980s, the legislature ceased using multi-member legislative districts.[96][f]

The passage of the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 ensured protections for racial minorities in elections and increased their electoral influence in the state.[98] Henry Frye became the state's first black legislator in the 20th century when he joined the House of Representatives in 1969.[99][100][101] The number of black legislators steadily increased in the 1970s and 1980s.[102] In 1973, Henry Ward Oxendine became the first Native American member of the legislature.[103][104] In 1994, Daniel F. McComas became the first Latino elected to the General Assembly.[105] Jay Chaudhuri became the first legislator of South Asian descent in 2016.[106]

In the 1994 elections, Republicans won control of the House of Representatives for the first time since the 1800s. In the 2010 elections, Republicans secured control of both the House and the Senate for the first time in over 100 years.[107] As of 2025, the Republicans have controlled both chambers since then.[108]

Membership

The General Assembly has 170 elected members, with 120 members of the North Carolina House of Representatives and 50 members of the North Carolina Senate.[109] Each represents a district.[110] Each house has the sole power to judge the election and qualification of its own respective members.[111] Legislators' are elected biennially in even-numbered years. Their terms of office begin at the start of the January following the year of their election.[112] There are no term limits for legislators.[113][114] All legislators swear a state constitutionally prescribed oath of office.[115] In the event of the vacancy of a seat, the governor is constitutionally obligated to appoint a person nominated by the previous incumbent's political party's respective district executive committee to fill the seat.[116]

The assembly is styled after the citizen legislature model, with legislating considered a part-time job.[117][118][119] Members receive a base salary of $13,951 per year,[120] supplemented by per-diem payments and travel reimbursements.[121][122] Increases in legislative pay adopted by the assembly cannot take effect until after a succeeding election.[123]

Structure and process

Each house of the legislature has eight leadership roles. The Senate's leadership is made up of the president of the Senate, president pro tempore, majority leader, majority whip, majority caucus chair, minority leader, minority whip, and minority caucus chair.[124] Per the constitution, the office of president of the Senate is held ex officio by the lieutenant governor.[125] In this capacity they direct the debate on bills and maintain order in that house,[126][127] but have little influence over its workflow.[128] They cannot cast a vote in the Senate except to break ties.[129] The president pro tempore is elected by the full Senate. They appoint the body's committees. All other leadership positions are filled by the decision of party caucuses.[124]

The leadership of House of Representatives is analogous to that in the Senate, except that in place of a president and president pro tempore, the body is led by a speaker and speaker pro tempore. The speaker is in charge of appointing the body's committees. Both officers are elected by the full house from among its members, with the rest determined by party caucuses.[124][g] In the event of an even political divide in the House, co-speakers may be elected in lieu of a single speaker.[131]

Both houses appoint a principal clerk—who keeps their respective bodies' records, a reading clerk—who reads documents as required by the constitution, house rules, or the presiding officer, and a sergeant at arms—who maintains order in their house.[132] Standing committees in each house consider introduced legislation, hold hearings, and offer amendments.[131] All bills are examined by a body's respective rules committee before being brought before a full house for a vote.[133]

Powers

The constitution of North Carolina vests the state's legislative power in the General Assembly;[134] the General Assembly writes state laws/statutes.[111][110] Legislation in North Carolina can either be in the form of general laws or special/local laws. General laws apply to the entire state, while local laws apply only to specific counties or municipalities.[135][h] The constitution requires that all effective laws be styled "The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts:", with only the words following that phrase being legally operative.[111] The legally valid language of each passed bill is punctuated by the ratification certificate, consisting of the obligatory signatures of the presiding officers of each house.[138] Most laws have an "effective date" which stipulate the time they go into effect. Those that do not have an explicit stipulation go into effect 60 days after the assembly's adjournment sine die.[132]

The assembly has the power to levy taxes[139] and adopts the state budget.[140] The constitution enumerates a unique procedure for the passing of revenue legislation; all revenue bills must be read three times with each reading occurring on a different day, journal records of votes must include the name of each legislator and how they voted, and all revenue bills must appropriate money for a specific purpose.[141] The assembly is also responsible for drawing the districts of its own members[142] and the districts of the state's congressional delegation after every decennial U.S. census.[143] The legislative power of the assembly must be exercised by the whole body and not devolved upon a portion of the whole, and actions taken during one session of the assembly can be undone by a succeeding session.[144] The governor signs bills passed by the General Assembly of which they approve into law and are empowered to veto bills of which they disapprove.[145] A veto can be overridden by a three-fifths majority vote of the assembly.[146] Local bills and congressional and legislative reapportionment decisions are not subject to gubernatorial veto. Aside from regular legislation, the two houses of the General Assembly can also issue joint resolutions which are not subject to veto.[147]

The assembly wields oversight authority over the state's administrative bureaucracy.[148] It can alter gubernatorial executive orders concerning the organization of state agencies by joint resolution.[147] Its Joint Legislative Commission on Governmental Operations has the authority to seize state agency documents and inspect facilities of agencies and contractors with the state.[149] All legislative committees are empowered to subpoena the testimony of witnesses and documents.[150][151] The constitution allows for the General Assembly to provide for the filling of executive offices not already provided for in the constitution.[152] The body is also empowered to resolve contested elections for state executive officers by joint ballot.[111] Its advice and consent is required for the installation of some state agency heads. The assembly can also influence the bureaucracy through its power to create or dissolve agencies or countermand administrative rules by writing laws and by its decisions in appropriations.[148] The constitution empowers the House of Representatives to impeach elected state officials by simple majority vote. In the event an official is impeached, the Senate holds a trial, and can convict an official by two-thirds majority vote and remove them from office.[153] The General Assembly can also, by a two-thirds majority vote, determine the governor or a judge mentally or physically incapable of serving.[147]

The General Assembly has the sole power to propose amendments to the state constitution.[154] If a proposed amendment receives the support of three-fifths of the House and the Senate, it is scheduled for ratification by a statewide referendum. State constitutional amendments and state legislative votes on the ratification of federal constitutional amendments are not subject to gubernatorial veto.[155][147]

Sessions

The General Assembly's sessions are convened according to standards prescribed by the state constitution and state statute.[156] The General Assembly meets in regular session—or the "long session"—beginning in January of each odd-numbered year, and adjourns to reconvene the following even-numbered year for what is called the "short session". Though there is no limit on the length of any session, the "long session" typically lasts for 6 months, and the "short session" typically lasts for 6 weeks.[110][i] The legislature crafts its biennial state budget during the "long session" and typically only makes modifications to it during the "short session".[158] The house in which budget legislation originates alternates every biennium.[114] Typically the legislature adjourns shortly after June 30, the end of North Carolina's fiscal year, following the passing of a budget.[159] The governor may call the General Assembly into extraordinary session after consulting the North Carolina Council of State and is required to convene the assembly in specific circumstances to review vetoed legislation.[160] A majority of the Council of State can call the legislature into session to consider the governor's mental capacity to serve.[161]

A basic majority of the members of a house constitute a quorum to do business.[156] When in session, both houses of the legislature typically meet on Monday evenings and in the middle of the day on Tuesdays, Wednesdays, and Thursdays. Legislative committees usually convene in the mornings and late afternoons.[110] Committees sometimes meet when their house is not in session.[159] Both houses are empowered to temporarily adjourn for three days or less at their own discretion.[111] The proceedings of each house are constitutionally required to be reported in official journals and published at the end of each session.[123] Official transcripts of debates on the floors of the House and Senate are not produced, though audio of their sessions is recorded as well as the minutes of committee meetings.[162] The records of individual lawmakers are not subject to the state's public records law.[163] Each house chamber has a gallery from which members of the public can attend and observe sessions.[164]

Administration and support agencies

Administrative support of the General Assembly is overseen by the Legislative Services Commission, a panel comprising five members of each house.[110] As of October 2023, the assembly relies on over 600 support staff who work in the Legislative Building and the Legislative Office Building.[165] Daily operations of the legislature's facilities are directed by the legislative services officer.[165][166] Every legislator is assigned at least one legislative assistant or clerk who manage legislators' schedules, relay communications with constituents, and offer advice on policy issues. Some legislators employ additional staff.[167] The General Assembly's members and facilities are guarded by the North Carolina General Assembly Police.[168] The North Carolina Legislative Library serves as a repository of legislative documents and facilitates research for legislators and their staff.[169][170]

See also

- North Carolina State Capitol

- List of North Carolina state legislatures

- North Carolina Council of State

Notes

- ^ The constitutional structure of Carolina provided for autonomous government through counties, though only two, including Albemarle, were ever created under this framework. An assembly for the entire province was allowed but never created.[6]

- ^ Having been elected by the people, delegates to the convention regarded themselves as superior to the General Assembly and rejected an order from it to dissolve.[45]

- ^ The document still required officials to profess belief in a god.[48]

- ^ Computerization was authorized during the 1967 session following a trial program run during its course.[78]

- ^ During the 1973 session, the assembly voted to meet again during the following year.[81][82] This began the trend of holding a "short session" in between the regular sessions, mostly to discuss modifications of the budget.[83]

- ^ The state supreme court ruled that multi-member legislative districts were unconstitutional in 2001.[97]

- ^ The selection of a speaker from among the House's members is not strictly constitutionally required, but thus far has been the case.[130]

- ^ State jurisprudence is not exact on the delineation between and general and local legislation, though since 1987 state courts have judged whether a law affects "general public interests and concerns" to determine its status.[136] Additionally, local laws cannot effect over 15 counties, cannot change the name of a municipality, and cannot affect policy concerning ferries, bridges, cemeteries, juror compensation, or alter labor, trade, mining, or manufacturing regulations.[137]

- ^ Some "short sessions" have lasted longer than "long sessions".[157]

References

- ^ a b "Colonial Period Overview". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2024.

- ^ Butler 2022, p. 66.

- ^ Butler 2022, p. 68.

- ^ Butler 2022, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Butler 2022, pp. 69, 93.

- ^ Butler 2022, p. 72.

- ^ Butler 2022, p. 69.

- ^ Butler 2022, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Price, William S. Jr. (2006). "Governor's Council". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Norris, David A. (2006). "Instructions to Royal Governors". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Crow & Tise 2017, p. 45.

- ^ Stumpf, Vernon O. (1991). "Martin, Josiah". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c Butler, Lindley S. (2006). "Provincial Congresses". NCPedia. NC Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved July 26, 2024.

- ^ a b Howard, Josh (2010). "North Carolina in the US Revolution". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c Orth, John V. (2006). "Constitution, State". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ Mobley 2016, p. 59.

- ^ Cheney 1981, p. 795.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 6, 35.

- ^ a b c d Norris, David A. (2006). "General Assembly". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Barnes 1993, p. 4.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 12, 97.

- ^ Gerber 2009, p. 1813.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 14.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 6.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Mobley 2016, p. 60.

- ^ a b "History : In Need of a Capital City". North Carolina Historic Sites. North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties. Retrieved July 28, 2024.

- ^ Barnes 1993, p. 5.

- ^ Wheeler 1964, pp. 321–322.

- ^ Barnes 1993, p. 28.

- ^ "Bayard v. Singleton (C-20)". North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. December 7, 2023. Retrieved February 23, 2025.

- ^ Gerber 2009, pp. 1817–1818.

- ^ Barnes 1993, pp. 35, 37.

- ^ Barnes 1993, pp. 114, 116.

- ^ "Construction of The Capitol". North Carolina Historic Sites. North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Barnes 1993, p. 120.

- ^ Barnes 1993, pp. 120, 122.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 14, 97.

- ^ Cheney 1981, p. 796.

- ^ a b Barnes 1993, p. 122.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 16.

- ^ Cheney 1981, pp. 375–376.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 17.

- ^ Cheney 1981, pp. 376, 399.

- ^ Cheney 1981, p. 376.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 22.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Cheney 1981, p. 797.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 21, 115.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 20–21, 25.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 37.

- ^ "The Capitol in the 19th Century". North Carolina Historic Sites. North Carolina Division of State Historic Sites and Properties. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Justesen 2009, p. 285.

- ^ Balanoff 1972, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Justesen 2009, pp. 283–284.

- ^ Ijames 2008, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 24.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 26.

- ^ Edmonds 2013, pp. 3, 8, 14, 67.

- ^ Edmonds 2013, p. 37.

- ^ a b c Hunt, James L. (2006). "Disfranchisement". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved May 11, 2025.

- ^ a b Hunt, James L. (2006). "Fusion of Republicans and Populists". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved May 25, 2025.

- ^ Justesen 2009, pp. 284–285, 302.

- ^ Justesen 2009, pp. 284, 302.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 30.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 96.

- ^ Heath 1975, pp. 36, 44.

- ^ Cheney 1981, p. 625.

- ^ "The General Assembly Moves to Jones Street". North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. February 6, 2016. Retrieved July 12, 2024.

- ^ O'Connor 1994, p. 23.

- ^ "Post Mortem of the 1969 N.C. General Assembly". The Franklin Times. July 10, 1969. p. 1.

- ^ Heath 1969, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Potter 1975, pp. 28–30.

- ^ The 1969 General Assembly 1969, p. 13.

- ^ Warren 1969, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Luebke 1990, p. 43.

- ^ Hatch 1984, p. 33.

- ^ Crowell & Heath 1973, p. 2.

- ^ Dennis 1975, p. 13.

- ^ McLaughlin & Coble 2000, p. 6.

- ^ Crowell & Heath 1973, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Luebke 1990, p. 42.

- ^ O'Connor 1994, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Cooper & Knotts 2012, pp. 134–135.

- ^ Christensen, Rob (February 23, 2017). "The Arnold Schwarzenegger Of Legislatures". The Transylvania Times. Vol. 131, no. 16. p. 3A.

- ^ "First Step". Our State. April 28, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ "Gertrude Dills McKee (Q-51)". North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. January 23, 2024. Retrieved July 29, 2024.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 51.

- ^ Shinkle 1980, pp. 10–11.

- ^ O'Connor 1990, pp. 31–32.

- ^ O'Connor 1990, p. 32.

- ^ O'Connor 1990, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Cooper & Knotts 2012, pp. 155, 162.

- ^ Bitzer 2021, pp. 84–85.

- ^ "Voting Rights Act of 1965". John Locke Foundation. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ Schlosser, Jim; Alexander, Dave (January 15, 1969). "Frye Takes Oath Of Office". The Greensboro Record. p. A1.

- ^ Jordan 1989, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Leloudis & Korstad 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Jordan 1989, pp. 41–42.

- ^ Sider 2003, p. 91.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 47.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 45.

- ^ Eanes, Zachery; Chen, Shawna (September 26, 2024). "Asian American voters play a growing role in N.C. politics". Axios Raleigh. Axios Media. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ Rash, Mebane (December 11, 2024). "What you need to know about the evolution of party politics in North Carolina to understand the 2024 elections". EducationNC. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ Sethi, Nikhil; Kolenovsky, Zoe (February 4, 2025). "The NCGA no longer has a full Republican supermajority. What does that mean for NC Gov. Josh Stein?". Duke Chronicle. Retrieved May 23, 2025.

- ^ Fain, Travis (January 27, 2023). "Bills filed, votes to come. Here's how your NC General Assembly works". WRAL-TV. Capitol Broadcasting Company. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Structure of the North Carolina General Assembly". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Orth & Newby 2013, p. 104.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 96–97, 99.

- ^ Cooper & Knotts 2012, p. 161.

- ^ a b Brown, Chantal; Humphries, Ben (February 5, 2025). "As a new session begins, here's everything you need to know about North Carolina government". EdNC. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. Retrieved March 23, 2025.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 101, 165.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 100.

- ^ Osborne, Molly (July 28, 2023). "Does North Carolina have a full-time legislature?". North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Vitaglione, Grace (September 20, 2023). "NC politics still a tough play for millennials and Gen Z". Carolina Public Press. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Murphy, Brian (March 12, 2022). "NC lawmakers set record with long session. None like it, but what's the solution?". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Norcross, Jack (May 18, 2022). "North Carolina legislators among lowest paid in the US". WCNC Charlotte. WCNC-TV. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Vaughan, Dawn Baumgartner (February 14, 2023). "How do NC lawmakers compare to the rest of the state's population? What the data shows". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions : How much are legislators' travel and expense allowances?". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ a b Orth & Newby 2013, p. 103.

- ^ a b c Cooper & Knotts 2012, p. 163.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 122.

- ^ North Carolina Manual 2011, p. 159.

- ^ "Lieutenant Governor". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved August 22, 2022.

- ^ "Lt. Gov. Dan Forest". WRAL. Capitol Broadcasting Company. January 9, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 99, 122.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 102.

- ^ a b "Legislative Branch". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ^ a b "Frequently Asked Questions : Legislative Process". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved July 13, 2024.

- ^ Vaughan, Dawn Baumgartner (January 20, 2023). "These are the most powerful people deciding what bills become law in North Carolina". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 95–96.

- ^ Lawrence, David M. (2007). "The County as a Body Politic and Corporate". NCPedia. North Carolina Government & Heritage Library. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 111.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 124.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 106–107.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 55.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 118.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 104, 108–109.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 97.

- ^ "Legislative and Congressional Redistricting". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, p. 96.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 101, 104–105.

- ^ Cooper & Knotts 2012, p. 142.

- ^ a b c d Orth & Newby 2013, p. 107.

- ^ a b Cooper & Knotts 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Fain, Travis (November 10, 2023). "State agencies' plan for legislature's new investigation powers: Ask a lawyer". WRAL-TV. Capitol Broadcasting Company. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Fain, Travis (February 20, 2018). "General Assembly leaders hint at subpoena over pipeline fund". WRAL-TV. Capitol Broadcasting Company. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Broughton, Melissa (February 24, 2017). "As senators subpoena Cooper cabinet pick, experts weigh legal options, potential outcomes". NC Newsline. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 117, 122.

- ^ Sáenz, Hunter (February 11, 2021). "VERIFY: Is there an impeachment process in North Carolina?". WCNC Charlotte. WCNC-TV. Retrieved November 14, 2023.

- ^ Doyle, Steve (August 9, 2023). "Could North Carolina voters change the process for adopting constitutional amendments? Check out the various practices". Fox 8 WGHP. Nexstar Media Group. Retrieved November 20, 2023.

- ^ Anderson, Bryan (March 16, 2023). "Cooper's Veto Predicament". The Assembly. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ a b "When is the General Assembly in Session?". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved November 6, 2023.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 95.

- ^ Cooper 2024, p. 98.

- ^ a b "North Carolina General Assembly Primer" (PDF). Duke Relations. Duke University. September 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2024.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Orth & Newby 2013, pp. 101, 125.

- ^ "Home". North Carolina Legislative History Research. State Library of North Carolina. Retrieved February 16, 2025.

- ^ Vaughan, Dawn Baumgartner (October 16, 2023). "How 'a couple of very powerful individuals' gave themselves more power in NC budget". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Visitor Info : Attending Sessions". North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved July 9, 2024.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Dawn Baumgartner; Raynor, David (October 27, 2023). "How much do NC General Assembly employees make? What raises did they get? See the data". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ Campbell, Colin (January 2, 2024). "Buildings coming down, offices moving for Raleigh state government overhaul". WUNC 91.5. WUNC North Carolina Public Radio. Retrieved July 16, 2024.

- ^ Lu, Jazper (July 27, 2023). "Are NC legislators allowed to date staff members? Here's what their rules say". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ McDonald, Thomasi (September 12, 2017). "Why is there a special police car parked each day in front of the General Assembly?". The News & Observer. Retrieved November 12, 2023.

- ^ "Welcome to the Library!". North Carolina Legislative Library. North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

- ^ "About Us". North Carolina Legislative Library. North Carolina General Assembly. Retrieved February 22, 2025.

Works cited

- "The 1969 General Assembly Faces Major Challenges". Popular Government. Vol. 35, no. 5. UNC Institute of Government. February 1969. pp. 11–13.

- Balanoff, Elizabeth (January 1972). "Negro Legislators in the North Carolina General Assembly, July, 1868-February, 1872". The North Carolina Historical Review. 49 (1): 22–55. JSTOR 23529002.

- Barnes, Henson P. (1993). Work in Progress : The North Carolina Legislature. Raleigh: North Carolina Legislature. OCLC 30882050.

- Bitzer, J. Michael (2021). Redistricting and Gerrymandering in North Carolina: Battlelines in the Tar Heel State. Springer Nature. ISBN 9783030807474.

- Butler, Lindley S. (2022). A History of North Carolina in the Proprietary Era, 1629-1729. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469667577.

- Cheney, John L. Jr., ed. (1981). North Carolina Government, 1585-1979: A Narrative and Statistical History (revised ed.). Raleigh: North Carolina Secretary of State. OCLC 1290270510.

- Cooper, Christopher A. (2024). Anatomy of a Purple State : A North Carolina Politics Primer. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469681719.

- Cooper, Christopher A.; Knotts, H. Gibbs, eds. (2012). The New Politics of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-0658-3.

- Crow, Jeffrey J.; Tise, Larry E., eds. (2017). Writing North Carolina History. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469639499.

- Crowell, Michael; Heath, Milton S. Jr. (May 1973). "The 1973 North Carolina General Assembly". Popular Government. Vol. 39, no. 8. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 1–11, 58.

- Dennis, Stephen N. (1975). "Recent Changes in the Appropriations Process". Popular Government. Vol. 40, no. 4. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 11–17.

- Edmonds, Helen G. (2013). The Negro and Fusion Politics in North Carolina, 1894-1901 (revised ed.). Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469610955.

- Gerber, Scott D. (September 2009). "The Origins of an Independent Judiciary in North Carolina, 1663-1787". North Carolina Law Review. 87 (6): 1771–1818.

- Hatch, Richard W. (1984). "News Coverage of the General Assembly, Past and Present". Popular Government. Vol. 49, no. 4. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 32–36.

- Heath, Milton S. Jr. (September 1969). "The 1969 North Carolina General Assembly". Popular Government. Vol. 36, no. 1. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 1–10.

- Heath, Milton S. Jr. (1975). "Interim Legislative Studies". Popular Government. Vol. 40, no. 4. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 36–44.

- Ijames, Earl (2008). "African American Political Pioneers". Tar Heel Junior Historian. 48 (1): 24–25.

- Jordan, Milton C. (December 1989). "Black Legislators: From Political Novelty to Political Force" (PDF). N.C. Insight. Vol. 12, no. 1. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. pp. 40–54, 58.

- Justesen, Benjamin R. (July 2009). "'The Class of '83': Black Watershed in the North Carolina General Assembly". The North Carolina Historical Review. 86 (3): 282–308. ISSN 0029-2494. JSTOR 23523861.

- Leloudis, James L; Korstad, Robert R. (2020). Fragile Democracy: The Struggle over Race and Voting Rights in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9781469660400.

- Luebke, Paul (1990). Tar Heel Politics : Myths and Realities. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-4271-0.

- McLaughlin, Mike; Coble, Ran (February 2000). "Does North Carolina Have a Citizen Legislature?" (PDF). N.C. Insight. Vol. 18, no. 4. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. pp. 2–17.

- Mobley, Joe A. (2016). North Carolina Governor Richard Caswell: Founding Father and Revolutionary Hero. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62585-817-7.

- North Carolina Manual (PDF). Raleigh: North Carolina Department of the Secretary of State. 2011. OCLC 2623953. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 2, 2023. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- O'Connor, Paul T. (December 1990). "Reapportionment and Redistricting: Redrawing the Political Landscape" (PDF). N.C. Insight. Vol. 13, no. 1. pp. 30–49.

- O'Connor, Paul T. (January 1994). "The Evolution of the Speaker's Office". N.C. Insight. Vol. 15, no. 1. North Carolina Center for Public Policy Research. pp. 22–29, 32–41, 43–45.

- Orth, John V.; Newby, Paul M. (2013). The North Carolina State Constitution (second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-930065-5.

- Potter, William H. Jr. (1975). "Staff Services to the North Carolina General Assembly". Popular Government. Vol. 40, no. 4. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 27–30.

- Shinkle, Kathy (1980). "Women Legislators : facing a double bind" (PDF). N.C. Insight. Vol. 3, no. 4. N.C. Center for Public Policy Research. pp. 10–15.

- Sider, Gerald M. (2003). Living Indian Histories: Lumbee and Tuscarora People in North Carolina (revised ed.). Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books. ISBN 9780807855065.

- Warren, David G. (June 1969). "A Computer Information System for the North Carolina General Assembly". Popular Government. Vol. 35, no. 9. UNC Institute of Government. pp. 1–6.

- Wheeler, E. Milton (July 1964). "Development and Organization of the North Carolina Militia". The North Carolina Historical Review. 41 (3): 307–323. JSTOR 23517532.

External links

- Online archive Archived March 2, 2019, at the Wayback Machine of the North Carolina Legislative Journals of the General Assembly, 1822 to the present, from the State Library of North Carolina.

- Online archive Archived June 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine of the Public Documents of North Carolina containing executive and legislative documents produced for each year's General Assembly session, 1831 to 1919, from the State Library of North Carolina.

- Online archive Archived August 12, 2021, at the Wayback Machine of the Session Laws of North Carolina, which include all ratified bills and resolutions in a given session of the General Assembly, 1817 to 2011, from the State Library of North Carolina.

- Guide to the Session Laws of North Carolina Archived December 6, 2019, at the Wayback Machine