Summary

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. As of 2022, the current General Assembly is the 102nd.

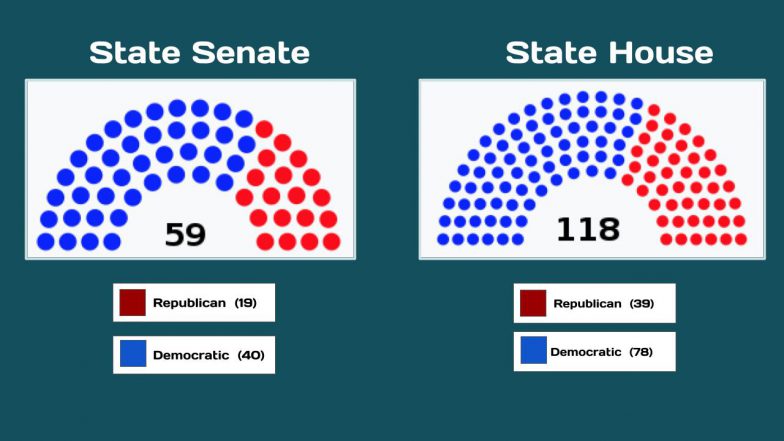

Under the Illinois Constitution, since 1983 the Senate has had 59 members and the House has had 118 members. In both chambers, all members are elected from single-member districts. Each Senate district is divided into two adjacent House districts.

The General Assembly meets in the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield, Illinois. Its session laws are generally adopted by majority vote in both houses, and upon gaining the assent of the Governor of Illinois. They are published in the official Laws of Illinois.

Two future presidents of the United States, Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama, began their political careers in the Illinois General Assembly–– in the Illinois House of Representatives and Illinois Senate, respectively.

OnAir Post: IL General Assembly

News

Illinois lawmakers gave final approval in the early hours of Friday morning to a new congressional redistricting plan that divides the state into 17 districts, one fewer than it currently has due to its loss of population since the 2010 U.S. Census.

It was the fourth draft plan that legislative Democrats had proposed over the previous two weeks, and it was introduced to the public after 7 p.m.

Like earlier versions, it collapses two southern Illinois districts into a single district while carving up much of downstate Illinois into a number of oddly-shaped districts that put cities as far apart as East St. Louis and Champaign into one district, with Bloomington and Rockford linked in another.

“This will be the most gerrymandered map in the country,” Sen. Don DeWitte, R-St. Charles, said during floor debate. “And this process will be used as the poster child for why politicians should never be allowed to draw their own maps.”

But Senate President Don Harmon, D-Oak Park, who carried the bill on the floor of the Senate, defended the maps, saying, “I’m here to stand behind the work we’ve done.”

“We’ve shown our maps to the public. We have presented them in hearing after hearing after hearing. We have refined them based on the input that we’ve gotten. And I’m proud of this map,” he said.

Capitol News illinois, – August 31, 2021

SPRINGFIELD – The Illinois House failed to muster the votes Tuesday to accept Gov. JB Pritzker’s amendatory veto to an ethics bill that passed nearly unanimously earlier this year.

Pritzker issued the amendatory veto of Senate Bill 539 Friday, saying he supports the legislation but would like to see a minor change in language dealing with the office of executive inspector general.

The Senate approved that technical change unanimously, but the trouble for the governor came in the House as Republicans removed their support for the bill and not enough Democrats remained in the chamber just before 10 p.m. Tuesday to reach the three-fifths vote needed for it to pass.

Gov. JB Pritzker signed a pair of bills Friday, June 4, that redraw state legislative and appellate court districts, despite the fact that official U.S Census data needed to ensure equal representation has not yet been delivered.

In a statement released Friday afternoon, Pritzker said he signed the measures after reviewing the maps to make sure they complied with state and federal law by ensuring minority representation.

“Illinois’ strength is in our diversity, and these maps help to ensure that communities that have been left out and left behind have fair representation in our government,” Pritzker said in the statement. “These district boundaries align with both the federal and state Voting Rights Acts, which help to ensure our diverse communities have electoral power and fair representation.”

Reaction to Pritzker’s announcement was swift. House Speaker Emanuel “Chris” Welch called the signing “a win for the people of this great state.”

Capitol News Illinois, – June 1, 2021

Shortly after 1 a.m. Tuesday, the Illinois Senate passed a bill aiming to improve ethics standards for elected officials after it was filed just hours earlier.

An amendment to Senate Bill 539, introduced by Sen. Ann Gillespie, D-Arlington Heights, passed with bipartisan approval despite House Republicans’ concerns that it was watered down.

“This legislation takes the first steps in addressing some of the most egregious scandals in our state’s history,” Gillespie said in a news conference Monday night. “While it won’t end corruption overnight, it closes many of the loopholes that have allowed bad actors to game the system for decades.”

The measure passed the House 113-5 Monday and the Senate unanimously early Tuesday morning. The bill will only need a signature from the governor to become law.

About

Source: Wikipedia

History

The Illinois General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Initially, the state did not have organized political parties, but the Democratic and Whig parties began to form in the 1830s.

Future U.S. President Abraham Lincoln successfully campaigned as a member of the Whig Party to serve in the General Assembly in 1834.[3] He served four successive terms 1834–42 in the Illinois House of Representatives, supporting expanded suffrage and economic development. The Illinois Republican Party was organized at a conference held in Major’s Hall in Bloomington, Illinois on May 29, 1856. Its founding members came from the former Whig Party in Illinois after its members joined with several powerful local political factions including, notably, the Independent Democrat movement of Chicago that helped elect James Hutchinson Woodworth as mayor in 1848.

During the election of 1860 in which Lincoln was elected president, Illinois also elected a Republican governor and legislature, but the trials of war helped return the state legislature to the Democrats in 1861.[4] The Democratic-led legislature investigated the state’s war expenditures and the treatment of Illinois troops, but with little political gain.[4] They also worked to frame a new state constitution nicknamed the “Copperhead constitution”, which would have given Southern Illinois increased representation and included provisions to discourage banking and the circulation of paper currency.[4] Voters rejected each of the constitution’s provisions, except the bans on black settlement, voting and office holding.[4] The Democratic Party came to represent skepticism in the war effort, until Illinois’ Democratic leader Stephen A. Douglas changed his stance and pledged his full support to Lincoln.[4]

The Democratic Party swept the 1862 election.[4] They passed resolutions denouncing the federal government’s conduct of the war and urging an immediate armistice and peace convention in the Illinois House of Representatives, leading the Republican governor to suspend the legislature for the first time in the state’s history.[4] In 1864, Republicans swept the state legislature and at the time of Lincoln’s assassination, Illinois stood as a solidly Republican state.[4]

In 1877, John W. E. Thomas was the first African American elected to the legislature.[5] In 1922, Lottie Holman O’Neill was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, becoming the first woman to serve in the Illinois General Assembly.[6]

From 1870 to 1980, the state was divided into 51 legislative districts, each of which elected one senator and three representatives. The representatives were elected by cumulative voting, in which a voter had three votes that could be distributed to either one, two, or three candidates. This system was abolished with the Cutback Amendment in 1980. Since then, the House has been elected from 118 single-member districts formed by dividing the 59 Senate districts in half. Each senator is “associated” with two representatives.

Future U.S. President Barack Obama was elected to the Illinois Senate in 1996, serving there until 2004 when he was elected to the United States Senate.[7]

Terms of members

Members of the House of Representatives are elected to a two-year term without term limits.

Members of the Illinois Senate serve two four-year terms and one two-year term each decade. This ensures that Senate elections reflect changes made when the General Assembly is redistricted following each United States Census. To prevent complete turnovers in membership (except after an intervening Census), not all Senators are elected simultaneously. The term cycles for the Senate are staggered, with the placement of the two-year term varying from one district to another. Each district’s terms are defined as 2-4-4, 4-2-4, or 4-4-2. Like House members, Senators are elected without term limits.

Officers

The officers of the General Assembly are elected at the beginning of each even number year. Representatives of the House elect from its membership a Speaker and Speaker pro tempore, drawn from the majority party in the chamber. The Illinois Secretary of State convenes and supervises the opening House session and leadership vote. State senators elect from the chamber a President of the Senate, convened and under the supervision of the governor. Since the adoption of the current Illinois Constitution in 1970, the Lieutenant Governor of Illinois does not serve in any legislative capacity as Senate President, and has had its office’s powers transferred to other capacities. The Illinois Auditor General is a legislative officer appointed by the General Assembly that reviews all state spending for legality.[8]

Sessions and qualifications

The General Assembly’s first official working day is the second Monday of January each year, with the Secretary of State convening the House, and the governor convening the Senate.[9] In order to serve as a member in either chamber of the General Assembly, a person must be a U.S. citizen, at least 21 years of age, and for the two years preceding their election or appointment a resident of the district which they represent.[9] In the general election following a redistricting, a candidate for any chamber of the General Assembly may be elected from any district which contains a part of the district in which he or she resided at the time of the redistricting and reelected if a resident of the new district he represents for 18 months prior to reelection.[9]

Restrictions

Members of the General Assembly may not hold other public offices or receive appointments by the governor, and their salaries may not be increased during their tenure.[9]

Veto powers

The General Assembly has the power to override gubernatorial vetoes through a three-fifths majority vote in each chamber. The governor has different types of veto like a full veto and a reduction veto. If the governor decides that the bill needs changes, he will ask for an amendatory veto.[9]

See also

Reference

- “Illinois Legal Research Guide”. University of Chicago Library. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Decker, John F.; Kopacz, Christopher (2012). Illinois Criminal Law: A Survey of Crimes and Defenses (5th ed.). LexisNexis. § 1.01. ISBN 978-0-7698-5284-3.

- White, Jr., Ronald C. (2009). A. Lincoln: A Biography. Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4000-6499-1, p. 59.

- VandeCreek, Drew E. Politics in Illinois and the Union During the Civil War Archived June 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (accessed May 27, 2013)

- McClellan McAndrew, Tara (April 5, 2012). “Illinois’ first black legislator”. Illinois Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- “Lottie Holman O’Neill (1878-1967)”. National Women’s History Museum. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- Scott, Janny (July 30, 2007). “In Illinois, Obama Proved Pragmatic and Shrewd”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Uphoff, Judy Lee (2012). “The Governor and the Executive Branch”. In Lind, Nancy S.; Rankin, Erik (eds.). Governing Illinois: Your Connection to State and Local Government (PDF) (4th ed.). Center Publications, Center for State Policy and Leadership, University of Illinois at Springfield. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-938943-28-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2013.

- Constitution of the State of Illinois, ARTICLE IV, THE LEGISLATURE (accessed May 27, 2013)

External links

- Illinois General Assembly

- Laws of Illinois from Western Illinois University

- Illinois General Assembly at Ballotpedia

- Legislature of Illinois at Project Vote Smart

- Illinois campaign financing at FollowTheMoney.org

Wikipedia

Contents

The Illinois General Assembly is the legislature of the U.S. state of Illinois. It has two chambers, the Illinois House of Representatives and the Illinois Senate. The General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. As of 2025, the General Assembly is the 104th. The term of an assembly lasts two years.

Under the Illinois Constitution, since 1983 the Senate has had 59 members and the House has had 118 members. In both chambers, all members are elected from single-member districts and districts are drawn to represent generally equal populations and redrawn every ten years based on census returns. Each Senate district is divided into two adjacent House districts.

The General Assembly meets in the Illinois State Capitol in Springfield. Its session laws are generally adopted by majority vote in both houses, and upon gaining the assent of the Governor of Illinois. They are published in the official Laws of Illinois.[1][2]

Two presidents of the United States, Abraham Lincoln and Barack Obama, began their political careers in the Illinois General Assembly, in the Illinois House of Representatives and Illinois Senate, respectively.

History

The Illinois General Assembly was created by the first state constitution adopted in 1818. Initially, the state did not have organized political parties, but the Democratic and Whig parties began to form in the 1830s.

Future U.S. President Abraham Lincoln successfully campaigned as a member of the Whig Party to serve in the General Assembly in 1834.[3] He served four successive terms 1834–42 in the Illinois House of Representatives, supporting expanded suffrage and economic development. He later went to the presidency as part of then new Republican Party.[4]

In 1877, John W. E. Thomas was the first African American elected to the legislature.[5] In 1922, Lottie Holman O'Neill was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, becoming the first woman to serve in the Illinois General Assembly.[6]

Future U.S. President Barack Obama was elected to the Illinois Senate in 1996, serving there until 2004 when he was elected to the United States Senate.[7]

Size over time

The size of the General Assembly has changed over time. The first General Assembly, elected in 1818, consisted of 14 senators and 28 representatives.[8] Under the 1818 and 1848 Illinois Constitutions, the legislature could add and reapportion districts at any time, and by 1870 it had done so ten times.[9] Under the 1870 Illinois Constitution, Illinois was divided into 51 legislative districts, each of which elected one senator and three representatives.[9] The representatives were elected by cumulative voting, in which each voter had three votes that could be distributed among one, two, or three candidates. Due to the unwillingness of downstate Illinois to cede power to the growing Chicago area, the district boundaries were not redrawn from 1901 to 1955.[10]

After voters approved the Legislative Apportionment Amendment in 1954, there were 58 Senate districts and 59 House districts, which did not necessarily coincide. This new arrangement was conceived as a "little federal" system: the Senate districts would be based on land area and would favor downstate, while the House districts would be based on population. House members continued to be elected by cumulative voting, three from each House district.[11] With the adoption of the 1970 Illinois Constitution, the system of separate House and Senate districts was eliminated, and legislative districts were apportioned on a one person, one vote basis.[12] The state was divided into 59 legislative districts, each of which elected one senator and three representatives.

The cumulative voting system was abolished by the Cutback Amendment in 1980. Since then, the House has been elected from 118 single-member districts, which are formed by dividing each of the 59 Senate districts in half.[13] Each senator is "associated" with two representatives.

Terms of members

Members of the House of Representatives are elected to a two-year term without term limits.

Members of the Illinois Senate serve two four-year terms and one two-year term each decade. This ensures that Senate elections reflect changes made when the General Assembly is redistricted following each United States Census. To prevent complete turnovers in membership (except after an intervening Census), not all Senators are elected simultaneously. The term cycles for the Senate are staggered, with the placement of the two-year term varying from one district to another. Each district's terms are defined as 2-4-4, 4-2-4, or 4-4-2. Like House members, Senators are elected without term limits.

Officers

The officers of the General Assembly are elected at the beginning of each even-numbered year. Representatives of the House elect from its membership a Speaker and Speaker pro tempore, drawn from the majority party in the chamber. The Illinois Secretary of State convenes and supervises the opening House session and leadership vote. State senators elect from the chamber a President of the Senate, convened and under the supervision of the governor. Since the adoption of the current Illinois Constitution in 1970, the Lieutenant Governor of Illinois does not serve in any legislative capacity as Senate President, and has had its office's powers transferred to other capacities. The Illinois Auditor General is a legislative officer appointed by the General Assembly that reviews all state spending for legality.[14]

Sessions and qualifications

The General Assembly's first official working day is the second Wednesday of January each year. The Secretary of State presides over the House until it chooses a Speaker and the governor presides over the Senate until it chooses a President.[15] Both chambers must also select a Minority Leader from among the members of the second most numerous party.

In order to serve as a member in either chamber of the General Assembly, a person must be a U.S. citizen, at least 21 years of age, and for the two years preceding their election or appointment a resident of the district which they represent.[15] In the general election following a redistricting, a candidate for any chamber of the General Assembly may be elected from any district which contains a part of the district in which they resided at the time of the redistricting and reelected if a resident of the new district they represents for 18 months prior to reelection.[15]

Restrictions

Members of the General Assembly may not hold other public offices or receive appointments by the governor, and their salaries may not be increased during their tenure.[15]

Vacancies

Seats in the General Assembly may become vacant due to a member resigning, dying, being expelled, or being appointed to another office. Under the Illinois Constitution, when a vacancy occurs, it must be filled by appointment within 30 days.[16] If a Senate seat becomes vacant more than 28 months before the next general election for that seat, an election is held at the next general election. The replacement member must be a member of the same party as the departing member.[16] The General Assembly has enacted a statute governing this process.[17] Under that statute, a replacement member is appointed by the party committee for that district, whose votes are weighted by the number of votes cast for that office in the area that each committee member represents.[17][18]

The appointment process was unsuccessfully challenged before the Illinois Supreme Court in 1988 as an unconstitutional grant of state power to political parties, but the challenge failed.[18]

Vetoes

The governor can veto bills passed by the General Assembly in four different ways: a full veto, an amendatory veto, and, for appropriations only, an item veto and a reduction veto.[19] These veto powers are unusually broad among US state governors.[20] The line item veto was added to the Illinois Constitution in 1884.[21] The amendatory and reduction vetoes were new additions in the 1970 Constitution.[20]

The General Assembly can override full, amendatory and item vetoes by a three-fifths majority vote in both chambers.[19] It can override a reduction veto by a simple majority vote in both chambers.[22] If both chambers agree to the changes the governor suggests in an amendatory veto, these changes can be approved by a simple majority vote in both chambers. If the General Assembly approves an amended law in response to the governor's changes, the bill becomes law once the governor certifies that the suggested changes have been made.[22]

Joint Committee on Administrative Rules

By statute, the General Assembly has the power to block regulations, including emergency regulations, proposed by state administrative agencies.[23] This power is currently exercised by the Joint Committee on Administrative Rules (JCAR). JCAR is made up of 12 members, with equal numbers from the House and Senate and equal numbers from each political party.[24] It can block proposed rules by a 3/5 vote.[25] The General Assembly can then reverse the block by a joint resolution of both houses.[25]

JCAR was first established in 1978 and given only advisory powers.[26] The General assembly gave it the power to temporarily block or suspend administrative regulations for 180 days in 1980.[26] In September 2004, the General Assembly expanded this temporary suspension power into a permanent veto.[27] As the Illinois Constitution does not provide for a legislative veto, the constitutionality of this arrangement has been questioned.[28] Among the charges brought against Governor Rod Blagojevich in his 2009 impeachment trial was that he had not respected the legitimacy of JCAR blocking his rulemaking on healthcare in 2008.[28]

See also

Works cited

- Illinois Constitution of 1818

- Illinois Constitution of 1870

- Illinois Constitution of 1970

- Green, Paul M. (1987). "Legislative Redistricting in Illinois: An Historical Analysis" (PDF). Illinois Commission on Intergovernmental Cooperation. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- Miller, David R. (2005). 1970 Illinois Constitution Annotated for Legislators (PDF) (4th ed.). Illinois Legislative Reference Unit. Retrieved June 9, 2022.

References

- ^ "Illinois Legal Research Guide". University of Chicago Library. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- ^ Decker, John F.; Kopacz, Christopher (2012). Illinois Criminal Law: A Survey of Crimes and Defenses (5th ed.). LexisNexis. § 1.01. ISBN 978-0-7698-5284-3.

- ^ White, Jr., Ronald C. (2009). A. Lincoln: A Biography. Random House, Inc.ISBN 978-1-4000-6499-1, p. 59.

- ^ VandeCreek, Drew E. Politics in Illinois and the Union During the Civil War Archived June 25, 2012, at the Wayback Machine (accessed May 27, 2013)

- ^ McClellan McAndrew, Tara (April 5, 2012). "Illinois' first black legislator". Illinois Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- ^ "Lottie Holman O'Neill (1878-1967)". National Women's History Museum. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved December 1, 2015.

- ^ Scott, Janny (July 30, 2007). "In Illinois, Obama Proved Pragmatic and Shrewd". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ "Illinois Legislative Roster — 1818-2021" (PDF). Illinois Secretary of State. 2021.

- ^ a b Green 1987, p. 4.

- ^ Green 1987, p. 8.

- ^ Green 1987, p. 9.

- ^ Green 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Green 1987, p. 20.

- ^ Uphoff, Judy Lee (2012). "The Governor and the Executive Branch". In Lind, Nancy S.; Rankin, Erik (eds.). Governing Illinois: Your Connection to State and Local Government (PDF) (4th ed.). Center Publications, Center for State Policy and Leadership, University of Illinois Springfield. pp. 77–79. ISBN 978-0-938943-28-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 22, 2013.

- ^ a b c d Constitution of the State of Illinois, ARTICLE IV, THE LEGISLATURE (accessed May 27, 2013)

- ^ a b Article IV, Section 2(d), Constitution of Illinois, 1970

- ^ a b 10 ILCS 5/25-6

- ^ a b Miller 2005, p. 26.

- ^ a b Article IV, Section 9, Constitution of Illinois, 1970

- ^ a b Miller 2005, p. 36.

- ^ "The Veto Process" (PDF). Inside the Legislative Process. National Conference of State Legislatures. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 15, 2010. Retrieved June 10, 2022.

- ^ a b Article IV, Section 9(d), Constitution of Illinois, 1970

- ^ Falkoff, Marc D. (2016). "An Empirical Critique of JCAR and the Legislative Veto in Illinois" (PDF). DePaul Law Review. 65. Retrieved June 11, 2022.

- ^ Joint Committee on Administrative Rules. "About JCAR". Retrieved June 12, 2022.

- ^ a b Illinois Legislative Reference Unit (2008). Preface to Lawmaking (PDF). Retrieved June 9, 2022.

- ^ a b Falkoff 2016, p. 978.

- ^ Falkoff 2016, p. 981.

- ^ a b Falkoff 2016, pp. 950–951.